Berkes and Folke argue that to understand how humans affect

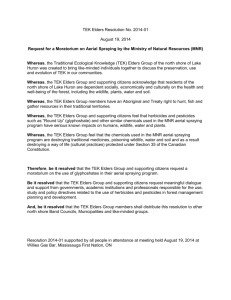

advertisement

NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 Valuing and utilising traditional ecological knowledge: tensions in the context of education and the environment Alan Reid, University of Bath Kelly Teamey, King’s College London Justin Dillon, King’s College London Abstract The paper discusses the ‘value-through-utility’ argument as a key ingredient of environmental educators’ interests in traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), and examines some of the epistemological and philosophical tensions it generates in employing TEK within the context of learning with sustainability in mind. In an earlier article (Reid, Teamey & Dillon, 2002), we argued that it is important to recognise that it is outsiders rather than insiders who usually conceptualise TEK. In this paper, we develop this point further, exploring the theorisation and practice of TEK-based environmental education in the context of discourses about sustainability and environmental education. Alan Reid is a lecturer at the Centre for Research in Education and the Environment within the Department of Education, University of Bath. His research focuses on environmental education policy and practice in England. Kelly Teamey is a doctoral student at King’s College London focusing on the linkages between poverty reduction and environmental education in development contexts (specifically Pakistan). Justin Dillon is a lecturer in science education in the Department of Education and Professional Studies, King’s College London. He is interested in the development of research strategies into questions of identity in a post-scarcity, environmentally problematic postmodern social condition. Contact address Alan Reid, CREE, Department of Education, University of Bath, BA2 7AY, UK Email: a.d.reid@bath.ac.uk Tel: +44 1225 386294 Fax: +44 1225 386113 1 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 Background The paper revisits Reid’s contribution to a conference held at the University of Bath (September 28-29, 2001) and sponsored by the Trumpeter: Journal of Ecosophy, on the theme of, “What kind of frame of mind could bring about sustainability - and how might we develop it?” (Reid, Teamey & Dillon, 2002). At the conference, Reid observed that such a question is not usually asked in education, nor does the role of traditional ecological knowledge appear to be considered in developing such a frame of mind, even when we are interested in why and how education might support the goals of sustainability. For the purposes of the Trumpeter conference, three types of response to the question were discussed: (i) those that focus on traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) as a concept, and suggest that it is flawed in some way or other; (ii) those that valorise TEK-based approaches to ecosystem management and ecological relationships as a Neo-Romantic paradigm to be championed in environmental education (for example, the myth of the ecologically noble savage, Buege, 1996); and (iii) those that explore the epistemological overlaps and tensions that conceptualisations of TEK raise— as a concept and as a body of knowledge—in environmental education and resource management, particularly in terms of competing accounts of knowledge, science and science education within environmental education discourse. Our initial analysis rejected the first two responses (Reid et al., op. cit.) and focused on identifying and exploring issues related to the third. We argued two main points. First, despite a number of criticisms that can be made about the conceptions, content and use of traditional ecological knowledge in environmental education, TEK is neither irrelevant to, nor incompatible with, modern scientific worldviews and paradigms that inform the dimensions of science and science education in what is constituted as ‘Western, scientific environmental education’. Gough (2002:1225), for example, notes Peat’s discussion of Blackfoot knowledge traditions in his critique of recent work on local traditions and global discourses (Yencken, Fien & Sykes, 2000), and argues that: Western cultures have no monopoly on forms of knowledge production that have the qualities that these authors attribute to ‘science’. Peat (1997, pp. 566-7) describes ‘the nature of Blackfoot reality’ as ‘far wider than our own, yet firmly based within the natural world of vibrant, living things … a reality of rocks, trees, animals and energies’. In recognising varying degrees of conflict or coherence in the discourse on environmental education, we drew on observations of recent trends in conceptions of science and ecosystem management, primarily those relating to ecosystems and ecosystem resilience (Golley, 1993; Berkes & Folkes, 1998). We also 2 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 suggested that when alternative conceptions are positioned by educators as arbitrary and contingent imperatives, such conceptual trends may even problematise the role and status of TEK as a challenge to the ‘science’ and ‘science education’ of environmental education within accounts of their various conceptions. This appears to be the case when it is argued that conceptions are generated within particular (rather than universal) matrices of culture, society, economy, environment, polity, etc. as opposed to being in inherent competition (Ball, 1994). Our second point focused on responses to TEK within forms of education that seek to hone ecological sensitivities or garner insights from the experience of a diversity of societies about sustainable resource management. We argued that educators’ and learners’ frames of mind should be characterised by respect, criticality and reflexivity in relation to traditional ecological knowledges. Teaching and learning through environmental education is often expected to include activities that are by, with, or about indigenous peoples, their environments, and the people’s relations to the living and non-living things around them. Such an approach can be traced to philosophical rather than pedagogic ‘first principles’ of environmental education, as promoted by UNESCO, the Agenda 21 process, and theorists such as Bowers. We also noted that since outsiders tend to conceptualise TEK rather than insiders, this state of affairs itself is important in a number of respects. While conceptions of TEK tend to be associated with the diversity of knowledge, innovations and practices that indigenous communities hold about the biophysical, socio-economic, and cultural-historical aspects of their local environment, they might also be defined in opposition to (‘Western’) modern, scientific conceptions of knowledge about ecosystems. This situation, we argue, is significant for understanding the ways in which we interpret the interests of environmental educators in traditional ecological knowledge in attempts to develop frames of mind that support goals associated with sustainability. Such goals include (but are not limited to) lifelong learning, the long-term sustainability of a local environment, poverty eradication, and community-based resource management - goals which are specifically linked to the processes and outcomes of education by the United Nations and by environmental NGOs: (i) after the UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro (UNCED, 1992); (ii) that have emerged in debates about the effectiveness of the Agenda 21 process over the last decade, and, (iii) in discussion around the significance and import of the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in 2002 in shaping the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2015). Thus the insider/outsider dilemma can be expressed as follows. It is impossible to become an ‘insider’ of TEK. As authors, ‘we’ have all been socialised within a Western, industrialised context. It is impossible for us to stand outside of the discourses that constitute each of us; this is the main paradox of discourses. Moreover, we recognise that discourse constrains the possibility of thought. Each discourse 3 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 establishes a different way of perceiving the world: altering and reproducing one’s ontology. Foucault (1972:49), for example, claims that it is impossible to gain access to universal truth since it is impossible to talk from a position outside of discourse; there is no escape from representation: Discourses are practises that systematically form the objects of which they speak. Discourses are not about objects; they do not identify objects, they constitute them and in the practice of doing so conceal their invention. The purpose of our analysis of discourse then is not to get ‘behind’ the discourse or to discover the reality behind the discourse. In a Foucauldian sense, reality can never be reached outside discourses and so it is discourse itself that has become the object of analysis. Through reflection it is possible to try and criticise our discourses, and TEK can be a tool to help us do this. However, we recognise that using TEK at any level is distorting it in accordance to the discourses that we are constituted by. Thus, our understandings of TEK are also distorted. With this brief sketch of prior arguments in mind, in this paper we focus on matters that, owing to space restrictions, were omitted in Reid, Teamey and Dillon (2002). We explore issues associated with ‘outsider’ educators valuing traditional ecological knowledge primarily on the basis of its utility as a concept (TEK) or as a body of knowledge (traditional ecological knowledges). In so doing, we draw on the work of Bowers, Payne, Noel Gough, and Berkes and Folkes to problematise a number of tensions this might raise in discussions of the philosophy and practice of environmental education. Valuing traditional ecological knowledge We start our discussion by revisiting two critical questions that might be asked of any interest: firstly, who is valuing this knowledge? And secondly, on what basis is this knowledge being valued? As an example, Gregoire and Lebner (2001:1), writing on behalf of the NGO Women’s Caucus of the UN’s Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD), state that: Valuing and applying women’s Traditional Environmental Knowledge (TEK) in its specific contexts is of vital importance for moving towards the preservation of the world’s biodiversity. Women’s TEK could also bring valuable insights for the advancement of health sciences. However, many groups and individuals, emphasize the economic value of TEK. Throughout their report, Gregoire and Lebner’s argument is intentionally feminist in its ideology and pragmatics. Their report recommends acknowledging women’s knowledge and experiences, and argues that educating women has a crucial impact on sustainable development and on changing the attitudes and behaviour of families, society and nations, owing to the relative distribution of gender roles in 4 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 agricultural production, care giving and domestic ‘chores’. This sits alongside an acknowledgment of the dominant (and dominating) value bases allied to ‘economic interests’ in traditional ecological knowledge. Thus, while they remark that the ‘keen cultural interest’ in TEK shown by aboriginal communities, environmental organisations and public interest/community groups is perhaps unsurprising, they go on to argue that the motives of commercial organisations, venture capitalists, or industrial developers——as the most prominent expressions of ‘economic interests’—should not go unquestioned on the one hand or be demonised on the other. They also contend that these interests are neither inevitable, incontrovertible or immutable. However, rather than pursue this line of investigation and deconstruct the variety of interests expressed here, we raise the possibility that the roots to an economic interest in traditional ecological knowledges are not necessarily dissimilar to those within Gregoire and Lebner’s first grouping of interests (on preserving biodiversity). They include the cultural interests expressed in the environmental positions advocated by a range of individuals and groups, which we exemplify in this paper through reference to the work of Corsiglia and Snively (1997), WWF (2000) and UNESCO (1999). Firstly, in championing its sources, heritage and integrity, Corsiglia and Snively (1997) present TEK about various ‘home-places’ as forming part of the richer knowledge and wisdom of ancient and contemporary long-resident peoples. While recognising its ‘intrinsic value’, TEK is portrayed as ‘a treasure-trove of important, field-tested, but historically neglected environmental knowledge and wisdom’ (p.1). Corsiglia and Snively (like other environmentalist positions in this discourse) value traditional ecological knowledges primarily through reference to TEK’s utility, applicability and pertinence to the problematics of environmental ‘management’ issues (see, though, Bowers (1993, 2001), and Reid et al., op. cit. and the priority given to examining theories of, and metaphors for, ‘development’ within environmental discourse). We identify this position as essentially a variant on the ‘value-through-utility’ argument, a stance towards traditional ecological knowledges that is also maintained within environment-orientated groups such as the international conservation organisation, WWF, and trans-governmental organisations that include UNESCO, as exemplified by its World Heritage, basic education, lifelong learning and environmental education programmes. To illustrate, WWF’s (2000) study of the world’s most biodiverse areas, Indigenous and Traditional Peoples of the World and Ecoregion Conservation, documents the rapid disappearance of languages spoken by indigenous and traditional peoples. A key claim in WWF’s report is that, through what often amounts to a long history of managing a particular environment, the ecological knowledge accumulated by these peoples comes to be embodied through language. Significantly, ‘language extinction’ leads to 5 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 the loss of ecological knowledge given that in many traditional cultures, knowledge may only be passed on to other groups or new generations orally (Hale, 1992a,b; Krauss, 1992). Yet, while it appears that WWF’s evaluation is principally based on TEK’s intrinsic value, utility soon emerges as a focus in terms of how insiders and outsiders manage that particular environment. For example, in terms of debating the focus, objectives and content of environmental education in relation to traditional ecological knowledges, it becomes important to recognise that WWF deliberately seeks to mobilise the interests of outsiders in specific ways. Actions by outsiders are justified on the grounds that they better inform endeavours to solve problems associated with resource depletion, burgeoning human populations, and the ecological disasters that increasingly affect many people groups. Furthermore, redress of ‘language extinction’ is attempted primarily through archiving initiatives, as supported by bodies such as UNESCO (e.g. the establishment of a global network of indigenous knowledge resource centres and the World Heritage programme); and studies, education programmes and participatory projects, such as those documented by WWF (2000), Berkes and Folke (1998) and Kasten (1998). Our point is that when we consider the discursive framing of such imperatives for archiving and applying traditional ecological knowledges as a body of knowledge, it typically resides within calls for the recognition of the consequences (intended or unintended) of other’s actions regarding resource use and management. For example, this may involve the evaluation or critique of past developments, technologies or ‘innovations’. Further discursive delineation may occur through reference to an increasingly globalised and interconnected cultural, social and economic network of people groups, and to temporal aspects of this interconnectedness, e.g. mobility, migration, plurality and conflict (Milton, 1996). What we might also recognise is that what such ameliorative actions cannot do is prevent traditional ecological knowledges, having been transformed into cultural artefacts and resources, then being put to use by other people with different ends in mind. Whether these ends are in fact nefarious or not, the irony of this situation is redolent of the disputes regarding the necessity, appropriateness and value of intellectual property rights (IPR) regimes for traditional ecological knowledges, and the politics of the construction and use of ecological knowledge discussed in our earlier commentary. This is particularly pertinent if educators come to treat TEK as little more than a cultural souvenir (see Reid et al., op. cit.). For example, viewed from the perspective of post-development critiques of knowledge and economy (by Escobar, Sen, Sachs, etc.), we note that ‘economic interests’ readily coincide with the dominant development discourses of neo-liberal economic theory. As the prevailing paradigm amongst Western 6 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 mode(l)s of development and progress, the value of TEK is understood in terms of further progress, greater efficiency, and tapping more/other potential forms of capital—in this case, traditional ecological knowledges become helpful as a form of human capital. The notion of TEK as a ‘treasure trove’ is particularly evocative here, and helps illustrate the strong coherence that may exist between cultural and economic expressions of interest in TEK. We also note that in this particular valuing of TEK by its diverse users, there is a second point of convergence that is closely related to the first. The notion of the ‘entrepreneurial knowledge engineering’ of ecological knowledge amounts to a leitmotif for the advocates of TEK-based resource management within environmental education and environmental management. The entrepreneurial engineering of ecological knowledge proceeds on the assumption that reworking existing ecological knowledge for application and dissemination in other contexts is both possible and desirable. This assumption may be in response to a perception or recognition of ecological risk, technological change, market constraints, participatory approaches to management, that existing knowledge is incomplete and fallible, and so on. Whatever the merits of these justifications though, we draw attention to the fact that the leitmotif might again be exemplified within the work of commentators such as Corsiglia and Snively (1997). Alongside many socially critical environmentalists and environmental educators, they contend that academic and pedagogic considerations of TEK-based systems should not position traditional ecological knowledges as exotic or esoteric, while simultaneously arguing from a deeply anthropocentric (technocentric and/or managerialist) perspective that TEK provides: ‘scientists, managers, governments and educators with important information and innovative strategies for implementing successful conservation and resource management approaches’ (ibid., p.1). Gough, Scott and Stables (2000) have already critiqued the possibilities of framing pedagogies ‘ecocentrically’ rather than ‘anthropocentrically’ within environmental education, in terms of weak and strong positions across this particular spectrum. Their analysis exemplifies the fact that the supporters of TEK-based resource management and environmental education are far from unanimous about the conceptualisation, utility and appropriation of others’ knowledge, which is where the leitmotif comes unstuck. Returning to our opening example, Gregoire and Lebner (2001:1, 4) comment that: The erosion of biodiversity constitutes an immense cultural loss and women, as bearers of knowledge and as main food producers and caregivers in most communities, have a major stake in the conservation of the basis of their livelihood and that of their families. Throughout the years, indigenous and rural men and women have developed different yet complementary knowledge systems, which need to be recognised and valued in the quest for sustainable development … TEK is socially-differentiated according to gender, age, occupation, socioeconomic status, religion, and other factors. It is therefore inappropriate to generalise about 7 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 indigenous or traditional knowledge without making proper distinctions … [or without addressing] the different structural positions of women and men and the question of access and control of resources (including land) as shaping the use of resources and the systems of traditional ecological knowledge. Such arguments, for example, are echoed in ecofeminist writings on environmental education and resource management, amongst other critical, radical and alternative perspectives. Shiva (1993), for instance, highlights the significance of the cultural distribution of knowledge through illustrating how all members of a community managing resources hold some knowledge, while other knowledge may only be common to particular ‘segments’ of that community (for example, women’s knowledge, men’s knowledge, or sacred knowledge only for the initiated). For environmental educators, Michie (1999) reiterates similar points about the distribution of knowledge and education, alongside raising questions about access to both. Of particular interest are concerns about, ‘the acknowledgment of ownership, and the protocols by which the knowledge can be obtained and to whom it can be transmitted’ (p.9). Such observations, Mitchie contends, serve as a means of distinguishing ‘proper’ from ‘improper’ use of TEK in environmental education. That is, valuing is explicitly linked with the use of TEK, and with pedagogical and cultural possibilities and priorities. Furthermore, while accounting for the deep-seated difficulties in resolving resource management issues, Michie argues that these concerns conflict with traditions in the West that treat knowledge as part of a common heritage. Such a perspective, it is noted, is found in much of the environmental education promoted through UNESCO (e.g. through the Belgrade, Tbilisi, Moscow and Thessaloniki conferences, recommendations and documentation (see the UNESCO journal, Connect, and UNESCO, 1999) and Agenda 21. Yet, because of ownership of patents or intellectual property rights, scientific knowledge systems can be just as inaccessible. It might also be due to the language it is enshrined in, or the places where it is physically kept, such as university libraries, specialist journals and conferences. Michie suggests: ‘In some ways this is similar to indigenous ways of accessing knowledge, except the rites of passage and discriminatory practices are less obvious’ (p.3). Chapter 36 of Agenda 21, of course, promotes public awareness as a prerequisite for public participation in decision-making, predicated on access to information. As such, although the value-through-utility argument remains an important aspect of the ways in which environmentalists ground the value they ascribe to TEK within educational contexts, it is incumbent on educators to note that this position and the commodification of others’ knowledge is contested and contestable by ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ alike (Gough, 2002). The work of the Living Earth Foundation (www.livingearth.org.uk), a community development NGO, illustrates this well in connecting environmental education, TEK and environmental management, when it argues: 8 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 By building partnerships with communities, Living Earth believes that indigenous knowledge and local experience may be combined with educational activities to help communities have a better understanding of their environment, develop their own projects and manage their own resources. Environmental education is used to stimulate discussion and debate. The aim of the environmental education is: To promote positive change. To enable communities to consider their impact on the environment. To enable people to make informed decisions on issues concerning their environment. To help alter activities which deplete natural resources and threaten sustainable livelihoods. To ensure that the environmental education is accessible to everyone, the … programme focuses on informal learning. Communities are able to assess their own needs and to prioritise development projects. Reframing education and traditional ecological knowledge So far we have suggested that a range of pedagogical and philosophical issues are important to thinking about knowledge in frameworks for environmental education. We would argue this is particularly the case where a framework seeks to avoid leaving ‘Western science’ as the ‘benchmark’ for evaluating competing or complementary knowledge claims (Reid et al., op. cit.). We previously noted (ibid.) that some ‘new paradigm’ frameworks reject verificationist (epistemologically) or conservative (politically) models of the relationship between science and traditional ecological knowledges, because such models tend to ‘reduce’ traditional ecological knowledges to an existing framework. Their frameworks may also expend with holistic and/or spiritual aspects of the worldviews and cosmologies embodied in other systems of knowledge (see Gough, 2002; Sterling, 2003). Berkes and Folke (1998), by way of contrast, offer an example of a ‘new paradigm’ framework, which, although derived from resource management, bears strong similarities to recent conceptions of environmental education as ‘sustainable education’ (Sterling, 2003). In this section of the paper, we introduce the key elements of this framework, before making a number of observations about the tensions alternative frameworks raise for, and within, environmental education through further consideration of the value-through-utility argument. a) Systemic perspectives Berkes and Folke (1998) argue that in order to make better sense of resource management and of how humans affect ecosystems in sustainable or unsustainable ways, it is useful to understand: 9 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 the basic structure of the ecosystem itself; the people involved and the technologies they use; the type of local knowledge developed and held by resource users; and the property rights that local users possess and can defend. Such elements, they contend, are fundamental to social-ecological accounts of how individuals interact within local, regional, national and global systems to generate regularised patterns of interaction, leading to sustainable or unsustainable outcomes. Accordingly, Holling, Berkes and Folke (1998) identify and attribute a worldwide crisis in resource management to the current inability to prescribe sustainable outcomes. Ecological ‘surprises’ in managed ecosystems, such as the collapse of cod stocks on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, are represented as challenges to the conventional science and management of natural resources. This, it is argued, is principally because resource management strategies have tended to omit or ignore TEK-based approaches in favour of ‘Western’ and/or ‘scientific’ approaches. In expressing these dichotomies, there is an echo of the observations made earlier about the tensions in definitions in the discourse (which we treat at greater length in Reid et al., op. cit.). For example, we might question how and why a social-ecological model omits reference to language, political or power structures within the given community, historical elements, cultural characteristics, and so on, as key dimensions to understanding such interactions. In this perspective, the role of environmental education—through developing understanding, values, capacities and empowerment—is largely that of contributing to sustainable living, as well as examining the complementary and/or competing conceptions of science, environment and ecosystem in these debates. Such a view though is often more tacit than explicit in Berkes and Folke’s work since they prioritise the sustainability of resources and the institutions developed to use resources as key foci for their studies. Nonetheless, the possibility of environmental education as a key aspect of ‘sustainable education’ (Sterling, 2003) is also present where systemic approaches and epistemologies underpin the rationale for particular educational processes and outcomes (p.352): Characteristically, these problems tend to be systems problems, where aspects of behaviour are complex and unpredictable and where causes, while at times simple (when finally understood) are always multiple. They are nonlinear in nature, cross-scale in time and in space and have an evolutionary character. This is true for both natural and social systems. In fact, they are one system, with critical feedbacks across temporal and spatial scales. 10 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 b) Linking management practices with educational practice Folke, Berkes and Colding (1998:417) present a summary of management practices that are grounded in their modelling as a vehicle for offering guiding principles for building resilience in social-ecological systems. These management practices are summarised in Figure 1, a listing that the authors suggest provides a series of starting points (rather than an exhaustive account) for the further identification of practices that might lead to ecosystem resilience, as well as socio-cultural and ecological sustainability. The guiding principles, ‘as social mechanisms behind these management practices’ (ibid.) consist of designing management systems that: (a) ‘flow with nature’, (b) enable the development and use of traditional ecological knowledge to understand local ecosystems, (c) promote self-organisation and institutional learning, and (d) develop values consistent with resilient and sustainable social-ecological systems. These systems underpin the management practices presented in sequence in Figure 1, which entail the monitoring and managing of specific resources, the management of landscapes and watersheds, and the managing of dynamic processes within the context of the renewal of ecosystems at multiple scales. [INSERT FIGURE 1 HERE] c) TEK as a contributor to the problematisation of educational practices and philosophies Within the epistemological framework for this model, Berkes and Folke emphasise that both scientific and traditional ecological knowledge systems continue to change and evolve by assimilating and drawing on ‘outsider’ as well as ‘insider’ knowledge, alternative models, paradigms and worldviews. Furthermore, TEK-based systems of knowledge become integral to the educational dimensions of resource planning and management. Hence, the contribution of TEK to environmental education is primarily that of focusing attention on its role in improving environmental and development strategies, for example: by helping identify cost-effective and sustainable mechanisms for poverty alleviation that are locally manageable and locally meaningful; by a better understanding of the complexities of sustainable development in its ecological and social diversity; and by helping to identify imaginative, innovative, and perhaps unexpected, pathways to sustainable human development that enhance local livelihoods, communities, and environments. Interestingly, while this may lead to uncertainty about the purposes and practices of environmental education in its current forms, it has been argued that well-documented inquiries attending to traditional ecological knowledge might inform learners better than science and science education in environmental education that focuses solely on the testing of hypotheses or models for environmental systems (e.g. Sterling, 2001, 2003). 11 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 We might ask then, what of the obstacles to such a radical vision for environmental education? Bowers (2001) suggests that ‘centralised’, ‘top-down’ and ‘modernist’ approaches to education found in the institutions, philosophies and practices of formal, bureaucratised education have trouble with systems of knowledge such as TEK-based approaches to developing ecosystem resilience. The result, according to Bowers, is that little credence is given to their role in developing frames of mind that could bring about sustainability. In the context of emerging conceptions of ecosystems and resource management, TEK has not (yet?) received complementary status to ‘Western science’. Nor, at first glance, does it appear to fit with the modes of thinking requiring solutions to environmental problems based on (a) scientific principles of repeatability and predictability, and (b) prevailing models of development (see Millar & Osborne, 1998; Dillon & Scott, 2002). Also, despite its apparent merits, traditional ecological knowledge, as either a concept or a body of knowledge, is not necessarily meaningful in terms of prevailing ways of organising learning (e.g. subject-based, didactic approaches), or to the community for which the education is intended (e.g. those who experience very little connection with ‘nature’). Hence, Bowers concludes that rather than respecting and exploring the differences, TEK tends to be ignored or maligned in education, whether by default or design. Traditional knowledge, modernist education, postmodern world? A key obstacle identified in Bowers’ analysis is that within the formal education sector, teachers and learners, administrators and governors, and parents and policy makers, are all enmeshed within other ‘priority’ discourses, namely, those dictated by such current policy mantras as ‘literacy’, ‘numeracy’, ‘management’, ‘empowerment’, ‘computers’ and ‘key skills’. Bowers regards traditional ecological knowledge and its application as essentially problematic in this context. In being associated with ‘local’ or ‘indigenous knowledge’, TEK joins their long history of being devalued or dismissed as ‘low stakes’ and ‘high risk’. Outsiders, particularly those in positions of power and authority in education, have not considered the custodians of such knowledge ‘traditional’, appropriate or authoritative, or that the knowledge itself is ‘rich’, generalisable or illuminative, for teaching or learning (cf. Black, 2001). If it is seen to have potential, the dominant perspective in education appears to be that it is often in need of some renewal and new truth, usually from ‘Western science’. Likewise, Bowers argues, it often appears that there is a need for the transformation and reduction of TEK, by communicators and mediators, for display and application to other, often more constrained, contexts. In effect, TEK has little place in contemporary and modern education in the 21st Century owing to a series of obstacles throughout educational policy and institutions. The body of knowledge has moved on —different kinds and forms of knowledge are required—and knowledge relations between ‘providers’ and ‘consumers’ of knowledge have changed in such a way that learning (as the transmission of knowledge between and across generations and groups) is no longer deemed a credible educational philosophy (Bowers, 1993; cf. Payne, 2001). Ironically both broad and narrow in how education is 12 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 conceptualised, such a state of affairs can be exemplified in the paradoxical situation of environmental education programmes that position ‘learning’ as about development, empowerment, and capacity building, and in opposition to the transmission of (received) truths, (unsound) knowledge, and (mis)understanding (the parenthetical qualifications are intended to be nothing more nor less than illustrative of this point). Such a dichotomy is not to imply that TEK is not ‘allowed’ in environmental education, rather, some models of education are privileged over others, often to the detriment of that where the agency or authority in education is associated with ‘elders’ and ‘mentors’, tradition, wisdom, community and others’ authority over oneself (Bowers, 1993). Exploring this further, in the first part of these oppositional positionings, it appears that learning in environmental education is better thought of as being concerned with effecting self-organisation, autonomous decision-making and the emergence of novel solutions to existing environmental problems. As such, it fits much more readily with emancipatory and radical goals for education than with the ‘traditional’. Thus, with the second part, the ‘traditional’ in TEK-based approaches takes on a different hue. Viewed from the former perspective, it may become associated with notions of the primitive, simple, and static, or be taken to correspond with an inflexible adherence to the past, or a sentimentality or neo-Romanticism to be overcome through critical forms of education. Approached from one perspective only then, this amounts to a constricting use of the terminology and restricts ways of thinking about education. This is particularly the case when ‘traditional’ is understood to refer to the old, unchanging and undynamic, rather than being viewed as the integral, evolving aspect of the life of an ongoing community, of people and their territories, that avoids degrading the sustaining and self-renewing capacities of environments and ecosystems (Bowers, 2001). To illustrate the vividness of these tensions, we note that Agenda 21 promotes ‘proven educational methods and developed innovative teaching methods for educational settings without overthrowing appropriate traditional education systems in local communities’ (Article 36.5 f, UNCED, 1992). The eco-culture of critical environmental education Bowers’ attempt to defuse the apparent ferocity of the question, why should today’s educators and learners give space and time to subject matter and pedagogies that are outdated, outmoded, and out of touch with life and the issues of living in and beyond the 21st Century, is to emphasise the cultural roots of the ecological crisis. Firstly, he critiques the ‘culture of denial’ and ‘incessant, unthinking pursuit of innovation’ in education and resource management (Bowers, 2001). He also argues that educational theories that intend to be progressive and radical, such as those of Dewey, Freire, McLaren and Giroux, ignore the cultural roots of the ecological crisis we face. However radical and critical they might be of the capitalist system and its exploitation, such theories still ‘buy into the modern myths’ of anthropocentrism, linear progress, development and the autonomous individual as the basic social unit 13 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 (Bowers, 2001). According to Bowers, by doing this and by largely ignoring environmental degradation, these theories perpetuate the system they claim to criticise. Moreover, they fail to interpret and adapt the key messages and lessons of environmental, ecological and sustainable development education (e.g. Yencken et al., 2000). Nor do they take account of experience derived from their education programmes and their integral considerations of the interconnectedness of ecosystems, population, health, economics, social and human development, and peace and security (see, for example, Kelsey, 2001, on UNCED, 1992, and UNESCO, 1999). Thus, if TEK is conceived as solely associated with the idea of a system of knowledge, practices and beliefs, applied by ‘native peoples’ to present conditions in the same manner as to the past (where traditional is, consciously or not, equated with ‘pre-modern’), this is a decidedly narrow association. Indeed, we note that it has been argued that rather than TEK, the term, ‘indigenous knowledge of the land or ecosystem’, best captures the more holistic views of many indigenous peoples (Berkes, 1993; Berkes et al., 1998; Stevenson, 1996, 1997). Early studies of TEK, as an activity that tended to be both of and for outsiders, often focused solely on eliciting and analysing the terminologies by which people of different cultures classified the objects in their natural and social environments. Posey, in 1985 (pp. 139-140) for example, notes that: Serious investigation of indigenous ethnobiological/ethnoecological knowledge is rare, but recent studies ... show that indigenous knowledge of ecological zones, natural resources, agriculture, aquaculture, forest and game management, to be far more sophisticated than previously assumed. Furthermore, this knowledge offers new models for development that are both ecologically and socially sound. More recently, as environmental educators and theorists have developed (and we would argue, deepened) their responses to traditional ecological knowledge, the emphasis has changed from classification and application-oriented studies to a focus on understanding and interpreting the ecologically sound/sensible/smart practices that contribute to sustainable resource use among indigenous peoples. We would argue that these new studies lead to a better, critical understanding of the relationship of indigenous communities with their environment, between destructive knowledge traditions and those that are beneficial (see Bowers, 2001). What is often absent though, as we observed earlier in relation to Figure 1, is an explicit educational dimension to the strategies suggested for sustainable resource use, where education is regarded as fundamentally implicated within the development of worldviews. In this context, Foster (2001) has argued that education should be associated with developing a ‘deep sustainability’, non-instrumental mindset in relation to the putative role of teaching and learning in pursuing sustainability. In seeking 14 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 exemplification of this imperative, we might observe that Bowers illustrates Foster’s preferred frame of mind in his critique of problematic tendencies in current educational theory. The tendencies he cites include: the “emancipatory” theories of Dewey and others, the abuse of brain research to legitimise divisive educational practices, and what Bowers argues is the fundamentally flawed attempt to use computers to improve education (Bowers, 2001). To summarise, Bowers argues that each of the approaches to education that he criticises share the same problem: they are based on and reinforce cultural patterns that led to the ecological crisis in the first place. Of course, critics have argued that this has tended to obscure recognition of the fact that societies, traditions and cultures adapt and evolve, constantly adopting new ecological and educational technologies and practices (e.g. Payne, 2001). Yet, in moving towards the end of this paper, we reflect that, for us, a key implication of Bowers’ analysis is that any attempt truly to understand the other, and others’ knowledge, entails an attempt to understand ourselves—a position not without risk. In appropriating the knowledge, practice and experience of ‘the Other’, our purported ‘frames of mind’ do well to recognise our own ecological quests and attempts to solve our own ecological problems, hence the apparent necessity of both a response of humility and a sense of responsibility for our actions in this arena. Nevertheless, in attempting to appreciate, promote or protect TEK and other ways of knowing, in our concluding comments, we will argue that excessive reverence is a moral position and not a scholarly virtue; environmental educators need to prioritise critical enquiry rather than advocacy, however desirable the latter may be within wider society. Concluding comments Our argument then has been to oppose the view that TEK should avoid critique because of its sources, or to consider that it is misinterpreted and misconstrued by translation, mobilisation or reduction by others, even though these are distinct possibilities amongst environmental educators and resource managers. By engaging with the discursive frameworks of environmental education, we have not treated traditional ecological knowledge as a special case. Rather, we have attempted to show it can be studied or explained in a similar manner as other knowledge or knowledge traditions concerning the environment. If it is privileged, at risk is an a priori denial of the legitimacy of naturalistic, interpretivist or historicist explanations of TEK, within both expert and lay discourses on the environment and education. Likewise, treating traditional ecological knowledges as private, mysterious or ungraspable (for example, maintaining that making meaning of others’ knowledge requires affinity and empathetic understanding with the other and others’ knowledge), can result in TEK—its conceptions or substance—being removed from the scrutiny of public debate and analysis about its role in environmental education and resource management. 15 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 Put more positively, despite its limitations (Payne, 2001), we might continue to apply Bowers’ analysis at one step removed. From this distance, we regard Bowers’ work as helpful in asking that environmental educators address the work that TEK does; that is, by asking what power and privilege is generated, granted, and denied to people based on a particular construction of TEK? Within analysis of environmental discourse, similar questions have already been asked in relation to the politics and poetics of nostalgia, in the creation, perception and self-perception of subjectivity, and of identities and identity myths regarding ourselves and the world (Peters & Irwin, 2002; Payne, 2001). For example, the rhetoric of nostalgia, in being linked to particular ideas of authenticity, authority and tradition, has been mobilised across a panoply of eco-political ideologies (Peters & Irwin, 2002). This mobilisation can be viewed as part of an attempt to stabilise the configuration and perceived transmission of cultural and ecological identities within (environmental) education (see, for example, Payne, 2001, for a critical perspective on this). Perhaps crucially, as with the myth of the ecologically noble savage (Buege, 1996), in this particular framing, TEK appeals to some supposed ideal (premodern?) relationship between humans and the world: a mystical harmony and primeval wholeness of being which has been lost through the recent development of modern, industrial consciousness, whether seen from the perspectives of ‘deep time’ or an evolutionary timeframe. Nostalgia for an ideal primal state of human existence has often implied a rejection or devaluation of contemporary western society and its (alleged) materialism, and might even be morphed into an ideology of redemption through environmental education. Such an argument can be traced to the notion that authentic human relations are not possible in the ‘fallen’ West because unlike ‘pre-modern’ TEKbased communities, ‘we’ now have no sacred values, knowledge systems or relationships (the vocabulary of the argument is instructive here too). In this scenario, the value and utility of TEK in environmental education is positioned as that of teaching us how to return to, or rediscover, this premodern (sacred?) state. At the same time, TEK may be made immune to political criticism by an epistemological and philosophical position that maintains that TEK is sui generis and therefore only explicable within its own terms, and not by others factors such as power, psychology, or desire (see Payne, 2001). For both Payne and Bowers, in evaluating such diverse perspectives on the ‘teleology’ of environmental education, the tacit unquestioned attitude in education that TEK is a good and useful thing appears to represent little more than an unhelpful bias. In their own ways, both authors ask whether this attitude is questioned as a piece of ideology or is exposed as such, particularly when the idealisation of TEK within the kinds of redemption narrative as sketched above separates TEK from notions of power in environmental education and disguises its relationship to these powers (Grün, 1996). If ideologies are 16 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 regarded as ‘decontesting’ devices that attempt to confer cultural and conventional legitimacy on particular environmental relations, they narrow understandings of each of the political and pedagogical concepts they employ. The core concepts of much environmental discourse focus on the human-nature relation, nature preservation and variants of holism, together with an emphasis on appropriate human lifestyles. Following the approach of Gadamer, Grün argues against environmental education being an area of silence on such matters in the curriculum. He suggests this silence is due partly to the fact that the curriculum is shaped by Cartesian assumptions and by the general modernist project of forgetting the traditions into which we are born. As in our previous work (Reid et al., op. cit.), we read such critique as inferring that all conceptions of TEK are inevitably simplifying and problematic, in that in part, they are fashioned from, and defined against, what precedes and frames them as systems of ecological knowledge, whether the system is ‘insider’, ‘outsider’ or hybridising. Thus in ways akin to those of Payne and Bowers, Grün proposes that environmental educators restore the role of memory in curriculum, and come to terms with the past in the way recommended by Gadamer; for example, recognising that expectations and habits are naturalised in one epistemological framework, while assumptions are deeply problematical in others. TEK, we have argued, in becoming a ‘mine’ of discursive and pedagogical ‘resources’ for educators, raises questions about the vulnerability of others’ histories to appropriation and misinterpretation; more pointedly, TEK in education is seen to be equivocal and may be in the service of competing interests and ideologies. In conclusion then, we have pointed to the existence of strategies, explicit and tacit, that serve to promote the autonomy, integrity and priority of not simply the phenomena associated with TEK, but also those who interpret and apply this concept. If TEK is rendered privileged through strategies that insulate the user or TEK itself from uncomfortable questions about standpoint and partiality—as suggested by socio-political analysis of educators’ use of TEK within an environmental education that does not pay attention to historical agency or specificity—deleterious effects may be expected to follow (Payne, 2001; Gough, 2002). The process mishandled is inclined to govern, commodify and subjugate the people from whom it is derived. Or put less negatively, at the heart of developing a critical, reflexive response to TEK in environmental education is the necessity to ensure that the ideological and rhetorical strategies of dehistoricisation, universalisation, and decontextualisation do not go unquestioned by insiders and outsiders alike. 17 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 Figure 1: Social-ecological practices and mechanisms for resilience and sustainability 1. Management practices based on ecological knowledge Monitoring change in ecosystems and in resource abundance Total protection of certain species Protection of vulnerable stages in the life-history of species Protection of specific habitats Temporal restrictions of harvest Multiple species and integrated management Resource rotation Management of succession Management of landscape patchiness Watershed management Managing ecological processes at multiple scales Responding to and managing pulses and surprises Nurturing sources of renewal 2. Social mechanisms behind management practices a) Generation, accumulation and transmission of ecological knowledge Re-interpreting signals for learning Revival of local knowledge Knowledge carriers/folklore Integration of knowledge Intergenerational transmission of knowledge Geographical transfer of knowledge b) Structure and dynamics of institutions Role of stewards/wise people Community assessments Cross-scale institutions Taboos and regulations Social and cultural sanctions Coping mechanisms; short-term responses to surprises Ability to re-organise under changing circumstances Incipient institutions c) Mechanisms for cultural internalisation Rituals, ceremonies and other traditions Coding or scripts as a cultural blueprint d) Worldview and cultural values Sharing, generosity, reciprocity, redistribution, respect, patience, humility (Source: Folke, Berkes & Colding, 1998:418) 18 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 References BALL, S.J. (1994) Educational Reform: a critical and post-structural approach (Open University Press, Buckingham). BENTON, L.M. & SHORT, J.R. (1999) Environmental Discourse and Practice (Blackwell, Oxford). BERKES, F. (1993) Traditional knowledge in perspective, in: J.T. I NGLIS (Ed) Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Concepts and Cases (International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa). pp. 1-10. BERKES, F. & FOLKE, C. (Eds) (1998) Linking Social and Ecological Systems: management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge). BERKES, F., KISLALIOGLU, M., FOLKE, C. & GADGIL, M. (1998) Exploring the basic ecological unit: Ecosystemlike concepts in traditional societies, Ecosystems, 1, pp. 409-415. BLACK, P. (2001) Dreams, Strategies and Systems: portraits of assessment past, present and future, Assessment in Education, 8(1), pp. 65-85. BOWERS, C.A. (1993) Critical Essays on Education, Modernity, and the Recovery of the Ecological Imperative (Teachers College Press, New York). BOWERS, C.A. (2001) Educating for Eco-Justice and Community (University of Georgia Press, Athens). BUEGE, D.J. (1996) The ecologically noble savage revisited, Environmental Ethics, 18, pp. 71-88. COCHRAN, P.A.L. (1997) Traditional Knowledge Systems in the Arctic (Bering Sea Ecosystem Workshop, Anchorage, Alaska). CORSIGLIA, J. & SNIVELY, G. (1997) Knowing home, Alternatives Journal, Summer, 23(3). DILLON, J. & SCOTT, W. (Eds) (2002) Special Issue: Perspectives on Environmental Education-related Research in Science Education, International Journal of Science Education, 24(11). FOLKE, C., BERKES, F. & COLDING, J. (1998) Ecological practices and social mechanisms for building resilience and sustainability, in: F. BERKES & C. FOLKE (Eds) Linking Social and Ecological Systems (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge). pp. 414-436. FOSTER, J. (2001) Education as sustainability, Environmental Education Research, 7(2), pp. 153-165. GOLLEY, F.B. (1993) A History of the Ecosystem Concept in Ecology (Yale University Press, New Haven). GOUGH, N. (2002) Thinking/acting locally/globally: Western science and environmental education in a global knowledge economy, International Journal of Science Education, 24(11), pp. 1217-1237. GOUGH, S., SCOTT, W. & STABLES, A. (2000) Beyond O’Riordan: balancing anthropocentrism and ecocentrism, International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 9(1), pp. 36-47. GREGOIRE, H. & LEBNER, A. (2001) Re-evaluating Relevance: intellectual property rights and women’s traditional environmental knowledge, www.earthsummit2002.org/wcaucus/Caucus%20Position%20Papers/tek.htm. Accessed August 2001. GRÜN, M. (1996) An analysis of the discursive production of environmental education: terrorism, archaism and transcendentalism, Curriculum Studies, 4(3), pp. 329-347. HALE, K. (1992a) On endangered languages and the safeguarding of diversity, Language, 68(1), pp. 1-3. HALE, K. (1992b) Language endangerment and the human value of linguistic diversity, Language, 68(1), pp. 3542. 19 NOT FOR CIRCULATION – TO BE PUBLISHED IN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, 2004 HOLLING, C.S., BERKES, F. & FOLKE, C. (1998) Science, sustainability and resource management, in: F. B ERKES & C. FOLKE (Eds) Linking Social and Ecological Systems (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge). pp. 342-362. KASTEN, E. (1998) Handling ethnicities and/or securing cultural diversities: indigenous and global views on maintaining traditional knowledge, in: E. K ASTEN (Ed) Bicultural Education in the North: Ways of Preserving and Enhancing Indigenous Peoples’ Languages and Traditional Knowledge (Waxmann, Münster/New York). pp. 1-11. KELSEY, E. (2001) Reconfiguring public involvement: conceptions of “education” and “the public” in international environmental agreements (Unpublished doctoral thesis, King’s College London). KRAUSS, M. (1992) The World’s Languages in Crisis, Language, 68(1), pp. 4-10. MICHIE, M. (1999) ‘Where are Indigenous peoples and their knowledge in the reforming of learning, curriculum and pedagogy?’ Paper presented at the Fifth UNESCO-ACEID International Conference, Reforming Learning, Curriculum and Pedagogy: Innovative Visions for the New Century, 13-16 December (Bangkok, Thailand). MILLAR, R. & OSBORNE, J. (1998) Beyond 2000: Science education for the future (King’s College London School of Education, London). MILTON, K. (1996) Environmentalism and Cultural Theory: exploring the role of anthropology in environmental discourse (Routledge, London). PAYNE, P. (2001) Identity and environmental education, Environmental Education Research, 7(1), pp. 67-88. PEAT, F.D. (1997) Blackfoot physics and European minds, Futures, 29, pp. 563-573. PETERS, M. & IRWIN, R. (2001) Earthsongs: Ecopoetics, Heidegger and Dwelling, Trumpeter: Journal of Ecosophy, 18(1), 17 pp. http://trumpeter.athabascau.ca/content/v18.1/ REID, A., TEAMEY, K. & DILLON, J. (2002) Traditional ecological knowledge for learning with sustainability in mind, Trumpeter: Journal of Ecosophy, 18(1), 27 pp. http://trumpeter.athabascau.ca/content/v18.1/ SHIVA, V. (1993) Monocultures of the Mind: Perspectives on Biodiversity and Biotechnology (Zed Books, London). STERLING, S. (2001) Sustainable Education: Re-visioning Learning and Change (Green Books, Totnes). STERLING, S. (2003) Whole Systems Thinking as a Basis for Paradigm Change in Education: Explorations in the Context of Sustainability (Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Bath). STEVENSON, M. (1996) Indigenous knowledge in environmental assessment, Arctic, 49, pp. 278-291. STEVENSON, M. (1997) Ignorance and prejudice threaten environmental assessment, Policy Options, March, pp. 34-36. UNCED (1992) ‘Promoting Education, Public Awareness and Training’ Chapter 36, Agenda 21 (Regency Press, London). UNESCO (1999) Indigenous and local knowledge systems in sustainable development. UNESCO MOST meeting 8th November, Paris. WWF (2000) Indigenous and Traditional Peoples of the World and Ecoregion Conservation: An Integrated Approach to Conserving the World’s Biological and Cultural Diversity (WWF, Gland). YENCKEN, D., FIEN, J. & SYKES, H. (2000) The research, in: D. YENCKEN, J. FIEN & H. SYKES (Eds) Environment, Education and Society in the Asia-Pacific: Local Traditions and Global Discourses (Routledge, London). pp. 28-50. 20