Britain - Unlocking Buckinghamshire`s Past

advertisement

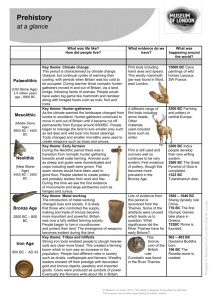

A trading county From the earliest times the people of what is now Buckinghamshire have been bartering and trading with distant parts of Britain and with far-flung places overseas. Use this exercise to start off the topic. You may need to discuss what the materials are. Sort this list of materials into what was available in Britain the past and what is only available today: Stone, plastic, glass, gold, silk, aluminium, silver, diamonds, pottery, flint, wood, iron, bronze, wool, Perspex, amber, garnet, nylon, leather, paper, rubber, ivory, jet, brick Once you have sorted them, think about where these materials can be found. Which ones can be found in Britain and which come from abroad? You could end up with tables that look like this (or you could sort by using mindmaps – see www.mind-mapping.co.uk): Old New Stone Wool Bronze Plastic Glass Amber Silver Aluminium Gold Garnet Silk Perspex Leather Paper Wood Nylon Rubber Pottery Ivory Flint Brick Iron To refine this and give some idea of when these materials were used from in Britain you could do a table like this and see if you can find any other materials: Neolithic Bronze Iron Age Age Wood Bronze Iron Stone Wool Gold Silver Amber Jet Pottery Flint Leather Roman Saxon Medieval Postmedieval Garnet Diamonds Rubber Paper Modern Silk Glass Ivory Brick Plastic Aluminium Perspex Nylon A trading county Do a similar table looking at which of the old items are from abroad and which are from Britain: Britain Abroad Wood Stone Gold Stone (some types) Pottery Flint Bronze Amber Silver Silk Paper Plastic Wool Garnet Rubber Pottery (some types) Leather Iron Glass Ivory Brick Again, this could be refined into which older items can be found or made in Buckinghamshire and what has to come from outside the county: Buckinghamshire Wood Stone Pottery Flint Leather Wool Iron Paper Brick Rest of Britain Stone (some types) Gold Bronze Glass Pottery (some types) Jet By sorting these, it will give your pupils a head-start in finding materials and artefacts in Buckinghamshire that have come from abroad in the past. Neolithic In prehistory the earliest tools were made from stone. While many of these were made from flint that was available locally, some were made from stone that could be polished to a high sheen and was often an attractive colour. The stone came from Cornwall, the Lake District or Scotland as well as the continent and was transported, either in roughed-out or finished form, around the UK and European mainland in the Neolithic period (c. 4000 – 2300 BC). These polished stone axeheads were probably little used but were prized as items of great symbolism. A A trading county polished greenstone axe from Cornwall was found in Bledlow Cop, a possible Early Bronze Age barrow. An axe-head found near End Cottage, Whiteleaf, was made of a type of stone called tuff, which seems to come from the Lake District. Another material that was prized in the Neolithic was amber. This came from the Baltic Sea where there are marine deposits of the fossilised tree resin. It is thought that some of the amber in Britain may have been washed up on the east coast rather than traded all the way from Scandinavia. A Neolithic amber bead was found in a pit in excavations at Coldharbour Farm before the Fairford Leys housing estate in Aylesbury was constructed. Figure 1: Neolithic polished stone axe possibly found in Wingrave Bronze Age Gold occurs naturally; you don’t have to smelt it from an ore. It is soft and workable at relatively low temperatures and it does not tarnish and lose its shine. It is only to be found in certain areas. There are gold mines, for instance, in Wales, Ireland and Central Europe. For all these reasons it was used in prehistory, mainly from the Neolithic onwards, as a status symbol. It was made into rings, bracelets and other jewellery, cups and other artefacts. The earliest gold artefacts in Buckinghamshire date to the Late Bronze Age, c.1000 – 700 BC. There are several rings, what archaeologists suggest may be ring-money, an early form of currency. These have been found in High Wycombe and Cublington. Late Bronze Age gold bracelets have been found at The Lee and in Waddesdon. In the Iron Age gold starts to be used for coins. These may not have been currency as we know it, but used to pay British mercenaries fighting against Caesar in Gaul, or given as gifts by chiefs to keep people loyal. Later gold coins from the Roman, Saxon and medieval periods were probably used much like we use coins today, though ours no longer have a lot of gold in them. A trading county Figure 2: Late Bronze Age socketed axes People started making and using lots of metal objects in the Bronze Age (c. 2300-800 BC). Bronze is made of two metals, copper and tin. There are no sources of either in Buckinghamshire. The main source of tin for much of Europe was Cornwall, and copper came from mines in Wales and Ireland. Some Irish metalwork seems to have been exported in a finished state, such as the socketed axe-head found in Akeley. Bronze Age boats are also known from Britain, attesting to movements of people and artefacts, and a dugout log-boat was found in the nineteenth century in the Thames at Bourne End. Unfortunately it was lost in 1880, so it is difficult to say whether it dated to the Bronze Age. Iron Age Iron was first used on a large scale in the Iron Age, hence its name. Iron ore is much more widespread than copper, so it means that iron artefacts can be produced locally. Gold coins arrived in Britain in the Iron Age. The earliest coin found in Buckinghamshire was Philip II of Macedon example found at Desborough Castle in High Wycombe. This type of coin was the prototype for Late Iron Age coins made in Gaul (France) and Britain. Amphorae were used to transport oil and wine from Rome governed Italy and Spain from the Late Iron Age, before Britain was brought into the Roman Empire. Several amphorae were found in a Late Iron Age burial at Vetches Farm in Aston Clinton and fragments have been found in excavations of villas at Yewden and Latimer. A trading county Figure 3: Late Iron Age gold coins found on Whaddon Chase Roman period The Roman period brought a new wave of trading. Samian ware, a type of pottery with a tough orange coating, was imported from central and southern Gaul (France). If you look on the Unlocking Buckinghamshire’s Past website, you will see just how much of this there is in the county. Part of a jet bowl and a jet spindle-whorl were found at Thorney in Iver and Wing Park respectively, at either end of the county. Jet came from Whitby in Yorkshire, so is another exotic import! The Romans also used ivory made of tusks from African or Indian elephants or from walruses to make pins, such as those found at the villa at Church Farm, Saunderton. A faience bead was found in a pit near a Roman pottery kiln at Fulmer in excavation in the 1960s. Faience is a type of opaque glass that was first made in Egypt, part of the Roman Empire. The bead from Fulmer may not have come all the way from Egypt, but the technology to make it did. Figure 4: Samian ware base (orange sherd) Figure 5: Roman Isis figurine from outside Buckingham A trading county The Romans also used special stone to make querns for grinding corn. Lava stone was very useful as it was quite rough and hard, as well as being lighter than the other common type used, millstone grit from Yorkshire. Lava stone was imported from northern Germany or the Mediterranean. We have fragments of Roman lava stone querns in Buckinghamshire, at Church Farm, Bierton, and Aylesbury High School in Walton. Lave stone was also imported later and there is a medieval specimen from the excavations at Main Street, Ashendon. The Romans didn’t only bring artefacts and materials from abroad with them, but also ideas. The native religion was merged with the Roman and later in the Roman period new cults from the Near East and Egypt started to arrive in Britain. A bronze figurine of the goddess Isis, the Egyptian goddess of fertility, was found at the Roman temple near Thornborough. Saxon period We always think of the Saxon period as the Dark Ages, where there is little evidence of what people were doing with their lives. This leads us to think that people living in the country at this date were very insular and had little to do with foreign cultures and didn’t travel very far. This is not the case. The Saxon burial in Taplow barrow was accompanied by a large number of very rich artefacts. Before Sutton Hoo (Suffolk) was excavated, or the Prittlewell burial (Essex) more recently, Taplow barrow was the richest Saxon burial found in Britain. One of the most spectacular artefacts found there was a bronze bowl, in a style often called a Coptic bowl, which would have come from either Byzantium, what is now Istanbul in Turkey, or from Egypt. Early Christians made Coptic bowls for ritual washing, but it is possible that they were used for something else entirely once they got to Britain. Figure 6: Gold clasp from Saxon burial at Taplow A trading county A buckle found in this burial was inlaid with garnets. Garnets were very popular in the Saxon period. They had to come a long way, though, from India or Sri Lanka. Garnets have also been found in Saxon brooches from Ashendon and Ivinghoe Beacon. Another Saxon burial at Ellesborough was found during the construction of the golf course. A cowrie shell that had been made into a pendant for a necklace was buried in the grave. This type of cowrie shell, a panther cowrie, comes from the Red Sea, between Africa and Asia (the Red Sea is bordered by Egypt and the Sudan on the west and Saudi Arabia on the east). A Merovingian style gold ring was found by a metal-detectorist in Cublington. The Merovingians were the ruling family of large parts of what is now France. Maybe this ring was brought over by someone from France or someone from Britain travelled on the continent and brought it back with them. Figure 7: Merovingian coin found in Cublington Medieval period A medieval amber rosary bead was found in a pit at Dorney. We have already seen how amber probably came from the Baltic Sea in Scandinavia. It was still popular in the medieval period too. Medieval people did much more travelling than we realise. It was relatively common to make a pilgrimage to a holy site to find a cure for a disease or to do penance for committing a sin. In fact, this practice started in the Roman and Saxon periods. By the medieval period, A trading county many people would buy lead or pewter pilgrim badges from the pilgrimage sites they visited to prove they had been there. Each site had its own symbol. One fourteenth to fifteenth century pilgrim badge in the shape of a crown was found at Walton Court. This may represent the crown of St Edward the Confessor, a Saxon king, whose shrine was at Westminster Cathedral. Another pilgrim token was an ampulla, a miniature phial possibly containing holy water that was worn round the neck. One of these was found in the grounds of Dinton Hall. It had an arrow on one side, suggesting that it came from Our Lady of Walsingham. Figure 8: Robert II of Scotland gold penny found on George Street, Aylesbury Medieval Scottish coins have been found in Buckinghamshire. One of Alexander III of Scotland was found on Mentmore village green and a Robert II penny was found on George Street, Aylesbury. Alexander III was king from 1249 to 1286. He married an English princess but refused to give tribute to England, maintaining Scotland was an equal kingdom. Robert II was the High Steward and often Regent of David II of Scotland before succeeding to the throne himself in 1371 after David II had threatened to make Edward III of England his heir. He was king until 1390. Scottish coins may have ended up in England when Scottish travellers came here, or when English men took part in the frequent wars with and raids on Scotland that happened over much of the medieval period. Post-medieval period A seventeenth century ivory comb was found on Hunter Street in Buckingham. The origins of ivory have been discussed above. It became very popular in this post-medieval period and many elephants were killed for their ivory. It is now illegal to do this. Seventeenth century Irish coins were found at Great Cockshoots wood High Wycombe and nineteenth century ones near the Plough Inn at Cadsden. It is possible that this represents an influx of Irish immigrants A trading county coming into England during very difficult times in Ireland when there were very bad famines and not much work. Rich people started to collect many artefacts from around the world in the seventeenth century. Chinese porcelain was very popular. Fragments of broken porcelain have been found in excavation in Boarstall and at Salden House Farm in Mursley. By the nineteenth century many of the collections were the basis of museums, such as the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the British Museum in London and our own Buckinghamshire County Museum. You can see Buckinghamshire County Museum’s Egyptian collection online at www.buckscc.gov.uk/museum/exhibitions/egyptians.htm. Explore later periods of trade on the National Archives Learning Curve website: www.learningcurve.gov.uk. You can also see some later artefacts that have been collected for the museum at www.buckscc.gov.uk/museum/m2e/index.htm. Some of the artefacts in the social history collection in particular are made of exotic materials like mahogany or were made abroad for export to Britain, like the Japanese bracelet or the Chinese fan. For the next activity you will need several maps of Buckinghamshire, which can be found on the Unlocking Buckinghamshire’s Past website. Using the finished map you could then explore how trade contacts change through prehistory and history. A trading county Your teacher will split the class into research groups to look for artefacts made of exotic materials from different periods that have been found in Buckinghamshire on the Unlocking Buckinghamshire’s Past website. Each group will research different periods: Prehistory (500,000 BC to AD 43) Roman (AD 43 to AD410) Saxon (AD 410 to AD 1066) Medieval (AD 1066 to AD 1539) Post-medieval (AD 1540 onwards) Your teacher will give you blank maps of Buckinghamshire for each research group. Each group has to mark what exotic materials they find on their maps. Then your teacher will print off a large map of the world and you have to draw a line linking the sites your group has marked on your Buckinghamshire map to the places the items came from in the world. Each period use a different coloured line. To finish the topic, you could have a discussion on why certain artefacts were seen as valuable and how they were moved about. How and why did these artefacts get moved about? Why would a garnet be so prestigious in the Saxon period? Why would people in the Roman period take so much effort to get the right type of stone for querns? Would there be merchants importing and exporting copper in prehistory? Or did artefacts get moved around as gifts from one person to another? www.buckscc.gov.uk/archaeology