Non Technical

advertisement

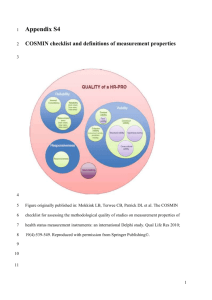

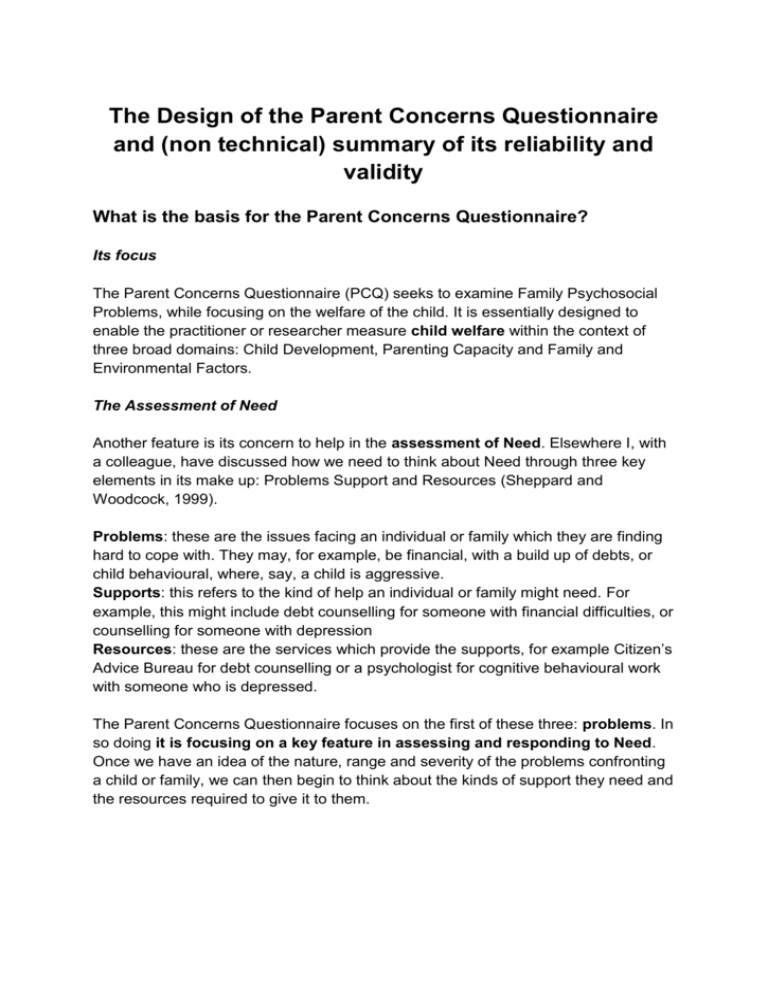

The Design of the Parent Concerns Questionnaire and (non technical) summary of its reliability and validity What is the basis for the Parent Concerns Questionnaire? Its focus The Parent Concerns Questionnaire (PCQ) seeks to examine Family Psychosocial Problems, while focusing on the welfare of the child. It is essentially designed to enable the practitioner or researcher measure child welfare within the context of three broad domains: Child Development, Parenting Capacity and Family and Environmental Factors. The Assessment of Need Another feature is its concern to help in the assessment of Need. Elsewhere I, with a colleague, have discussed how we need to think about Need through three key elements in its make up: Problems Support and Resources (Sheppard and Woodcock, 1999). Problems: these are the issues facing an individual or family which they are finding hard to cope with. They may, for example, be financial, with a build up of debts, or child behavioural, where, say, a child is aggressive. Supports: this refers to the kind of help an individual or family might need. For example, this might include debt counselling for someone with financial difficulties, or counselling for someone with depression Resources: these are the services which provide the supports, for example Citizen’s Advice Bureau for debt counselling or a psychologist for cognitive behavioural work with someone who is depressed. The Parent Concerns Questionnaire focuses on the first of these three: problems. In so doing it is focusing on a key feature in assessing and responding to Need. Once we have an idea of the nature, range and severity of the problems confronting a child or family, we can then begin to think about the kinds of support they need and the resources required to give it to them. Ecological Framework: Child Development, Parenting Capacity, Family and Environmental Factors In its most recent form (presented here) it has been organised into three domains: Child Development, Parenting Capacity and Family and Environmental Factors. This formulation makes it consistent with the British Common Assessment Framework (DfES, 2005), and the official publication A Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families (DoH, 2000). However, it is also consistent with the Ecological Framework for understanding child development which so influences policy and practice. The key feature of this approach is that we cannot think about child development or child welfare simply in terms of the child alone or even their interaction with their parents, but we must look at wider factors such as the family and social environment, particularly in the latter case social disadvantage (Zielinsky, 2006). Child Development: refers to the way the child matures as they grow older. The PCQ is concerned to discover if this process is in any way impaired: does the child have emotional problems? Do they have behavioural problems? How well do they socialise with other children? And so on Parenting Capacity refers to the ability of the parent to care for the child (or young person). The PCQ focuses on two key features, parenting tasks and parenting context. Parenting tasks refers to the direct interaction with and tasks of, the parent with the child, such as provision of guidance or involvement with the child (e.g. through play). Parenting context refers to the circumstances which might directly affect their performance of parenting task, such as illness, home management and depression Family and Environmental Factors refer to the context for child development and parenting. This includes features such as housing or financial problems, or difficult relations with friends or family. Generic Age appropriate Instrument There is a tension, in all instruments, between comprehensiveness – the extent to which it is able to feature in enough detail all relevant aspects – and efficiency – the need too create a questionnaire that can be completed with the least trouble and with enough speed so the person completing it does not lose interest. Some of the instruments developed for practice in recent years have lost sight of – or probably never actually had sight of – these considerations. We are now well aware, for example, of the extent to which the Integrated Children’s System has actually taken practitioners away from their primary task of working with children and their families. We wanted the PCQ to be quick and easy to use, yet also to have enough about it to provide a wide range of information for the assessment of need. We also wanted the instrument to have wide application and to be organised in a way that was appropriate for children’s social care services. We developed an instrument that could be generically used across age groups of children and young people. Thus the items were expressed in a way that could be applied to a child of any age, even though the particular feature may be manifested in different ways. Hence (child) emotional problems could well be manifested differently as between a two year old and a twelve year old, but the language used allowed it to be assessed for both age groups (the PCQ expressed child emotional problems as ‘the child is often upset, distressed or depressed’. It merely requires the parent to interpret each item in an age appropriate way. The PCQ has been developed to deal with the tensions – between comprehensiveness and efficiency - by adopting certain key approaches First we developed the PCQ for completion by the service using parent. The parent is the person liable to have most contact with the child and be responsible for that child. Hence it is critical to understand clearly their view of the situation. This is particularly the case with younger children, but it remains the case with teenagers. In most circumstances the best interests of the child is to be served by providing support for the parent (although it should be acknowledged that in cases of significant harm to the child this will not always be so). Nevertheless the parent is of huge significance to the child’s welfare. An old adage from social work (now sadly fallen into disuse) is ‘start where the client is’. It is important to know their perceptions as a basis for, if necessary further assessment, and certainly intervention. Second we sought to develop enough items or areas to provide a reasonably comprehensive picture of child and familial problems, without creating an instrument that would lose the interest of the service user. Hence we developed 37 items. Third we expressed each item in everyday language. Thus, ‘housing problems’ is expressed as ‘My housing is not good enough for my family's needs’; financial problems as ‘I have problems with money, such as debts or managing my money’; parental guidance as ‘I/we find control and discipline of the children is a problem’. Fourth the rating formula was very simple. In relation to each of the statements, there are three options: Not a problem; Present, but not severe; and Severe. Although providing only three options, its beauty lies in its simplicity, which provides clarity. If there is no problem there is nothing to worry about. If the problem is present, but not severe, this indicates that, which there, it was not taxing the parents personal resources or coping capabilities too far. A severe problem, however, is one which does present the parent with a real and serious challenge. It is clear from the use of the PCQ that parents understand this rating system clearly and are able to use it effectively to provide a questionnaire based ‘picture’ of their situation Fifth its generic nature, as outlined above, enables it to be used across age groups (which also enables it more easily to be used to assess outcome).. It is, therefore, in its simplicity that the strength of the PCQ lies. The tests of reliability and validity bear testament to the effectiveness with which it has been able to carry out its task of providing an initial assessment of child welfare in the context of familial psychosocial problems. What do these tests show? What is the Reliability and Validity of the Parent Concerns Questionnaire? The reliability and validity of an instrument is of huge importance both to researchers and practitioners who wish to use an instrument. In brief validity mean that an instrument is measuring what it says it is measuring and reliability means it does so consistently. In truth very few instruments in children’s social care meet these requirements (indeed most have not even been developed in a way that allows you to test for reliability and validity). Some exceptions – in that they have been tested for validity and sometimes reliability also - are in the pack accompanying the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families. However, these are not generic instruments. Rather they only look at specific aspects of a family’s situation, such as ‘Adult wellbeing’ or ‘alcohol dependence’. They do not provide an assessment of Child Welfare per se and are not instruments that may be generically used for this purpose. So if we are to discover whether an instrument is measuring what it says it is measuring and does so consistently, how can we do this? The Parent Concerns Questionnaire did so in a number of ways. First it has been used in three different contexts: users of children’s centres; applicants for children’s services; and users of children’s services, including those subject to a child protection plan (or in old terms those who were placed on the child protection register). This means both that it has been used in different contexts, but also that those contexts were at different ‘tiers’ (or stages of prevention). Hence the PCQ has been used with service using populations varying from open access universalist services available to everyone right through to services involving serious harm or potential serious harm to children. We have findings on reliability and validity that encompass these different settings There is scope for further application of the PCQ. For example it may have considerable potential for health centres/surgeries, nurseries and child and adolescent psychiatric settings. It has, though, yet to be used in these settings. On the basis of what we know so far – in particular that it is suitable for use at different tiers of service, we may reasonably expect the PCQ to be applicable and successful in these contexts. Second we needed to establish how reliability and validity could be established. How could we do this? Well there was no other instrument that examined Child Welfare in the way this has been done by the PCQ: that is a generic instrument, suitable for children’s social care services, to measure child welfare. Indeed there would be no point developing the PCQ if this was the case. Hence we could not simply put the PCQ up against this other (as it happens non existent!) instrument to see whether it measured child welfare in the same way. We therefore adopted a number of different approaches to establishing reliability and validity. How did we establish Validity? Since there is no other directly comparable (reliable and valid) instrument for the measurement of child welfare (suitable for children’s social care) we must find other ways of establishing its validity. First, the PCQ is a psychosocial measure – that is it measures problems at the interface of the psychological and social. Hence, if we were to establish its validity this would be best achieved by comparing it with other psychological and social measures, Second, however, it was not enough simply to focus on ‘the psychosocial’. It was necessary for the PCQ to be assessed against measures of features that might reasonably be expected to be associated with child welfare and family psychosocial problems. What measures did we use? From the realm of the (internal) psychological, We looked at PCQ scores against the presence or absence of depression using the Beck Depression Inventory We Looked at PCQ scores in relation to internal or external locus of control. Locus of control refers to the extent to which an individual feels they are able to control the direction of their life (in earlier, less gender aware times, this was referred to as a ‘sense of Mastery’). For this we compared PCQ scores with Pearlin’s Mastery Instrument From the interface of the psychosocial We looked at PCQ scores against a measure of stress. Stress was seen to have both internal (psychological) and external (social) dimensions. For this we used the Stress Appraisal measure From the Social We looked at PCQ scores against measures of disadvantage. The included income (whether or not the family was reliant on state benefit); housing (whether the house was rented or owner occupied); and marital status (whether this was a single parent family or not). We also looked at the PCQ in relation to family size. What should happen if the PCQ was valid? We should see some association, but not a perfect one, between each of these measures and the PCQ score. For example we should generally see a higher PCQ score for those families whose parents were depressed when compared with those where they were not depressed. Likewise we should see some association between PCQ score and reliance of a family on benefits. Why would we not expect a perfect association? Basically because we are not comparing the same thing. A measure of parental depression, for example, is not looking at the same thing as a measure of child welfare. However, we know very well that child welfare is affected by the presence of parental (particularly maternal) depression. Hence we would expect some association but not a perfect one. What were we looking for from these measures – what, in fact, should we reasonably expect? We would look for the following That child welfare problems would be higher amongst families with a depressed parent than non depressed (as measured respectively by the PCQ and Beck Depression Inventory) That Families with higher levels of child welfare problems would experience higher levels of stress than those with lower levels of child welfare problems (as measured respectively by the PCQ and Stress Appraisal Measure) That families with higher levels of child welfare problems would have parents more frequently characterised by an external locus of control (a sense that they were not in control of themselves and their environment), as measured by the PCQ and Mastery instrument That child welfare problems would be higher in disadvantaged families than other families (as measured by the PCQ and single parenthood, reliance on state benefit and not owning one’s own home). If we could establish that the PCQ operated in the ways predicted we would have very strong reasons for considering that it was valid as an instrument What did we find? The PCQ operated exactly as predicted. That is higher PCQ scores were associated with, respectively, the presence of parental depression, an external locus of control, higher levels of stress and measures of disadvantage. We can take an example. What was the difference in PCQ score according to whether or not a family suffered disadvantage? The answer was an unequivocal ‘yes’. The PCQ scores were markedly higher for families who were disadvantaged. The relationship between the measure of child welfare (PCQ score) and measures of disadvantage were operating as might be expected if the Parent Concerns Questionnaire were to be considered valid Average (mean) Parent Concerns Questionnaire Score related to measures of disadvantage PCQ Score PCQ Score PCQ Score Single Married-partner 17.0 11.2 Benefits reliant waged 16.1 8.3 Not house owner Owned house 11.2 8.6 A statistical note on Validity (miss this out if you don’t like stats!!) In statistical terms a perfect association (or correlation) has a score of 1.0. The score for no association at all is 0.0. So we would expect a correlation of between 0.0 and 1.0. There is no simple in principle ‘cut off’ point to establish validity (the degree of association found should reflect the actual association between two things – say child welfare and depression or child welfare and stress – and this may vary as between the different things looked at (Anastasi and Urbina, 1997)). As a rule of thumb, however, 0.3 is considered a moderate correlation and 0.4 is considered high. Thus these kinds of correlations are considered acceptable (Kaplan and Saccuzzo, 1997p 135). We found the following correlations (see Sheppard, 2010 for the technical analysis of reliability and validity) PCQ and Beck Depression Inventory: PCQ and Stress Appraisal Measure: PCQ and Mastery Instrument 0.58 0.49 0.36 Together with the findings on disadvantage these gave strong grounds to consider the PCQ to be valid (in technical terms it demonstrated construct and concurrent as well as face validity). Reliability In relation to reliability we needed to look at the consistency with which the PCQ measured child welfare. To what extent, in other words, was it stable, dependable and consistent? In this case we needed to establish its reliability in two ways: As a measure of Child Development, Parenting Capacity and Family and Environmental Factors, as well as Child Welfare as a whole (the ‘whole instrument’ measure) For this we needed to show that each of the areas, or items, making up each domain, was clearly an aspect of that domain. Are all the different items associated with each other in a way that we can meaningfully identify it as a domain? Hence we look at whether the association between the different areas or items making up the measurement of child development are sufficiently closely associated. Thus we would expect to find associations between child emotional, behavioural, cognitive and other problems to be such that we can genuinely say that they make up an overall measurement of Child Development (problems). Likewise Housing, financial occupational and other problems making up Family and Environmental Factors would be associated in such a way that we can say they make up an overall measurement of Family and Environmental Factors. In relation to all three domains (Child Development, Parenting Capacity and Family and Environmental Factors) we found associations providing clear evidence that each of these could legitimately be classified as a domain. The consistency with which the PCQ made measurements – that is, did it measure child development, parenting capacity and family and environmental factors consistently? To measure consistency we conducted a ‘test-retest’ approach. For this you get the same person to complete the instrument twice (a) close enough together to ensure that, for the majority of people, their situation had not changed, and that, therefore, if the instrument was consistent, you would get the same PCQ score and (b) nevertheless separate enough (in time) to ensure they were not completing the instrument on memory – that it was independently completed on each occasion. When we did this we found remarkably high levels of agreement between the first and second completions of the PCQ. It was therefore a highly consistent instrument in its measurements. Thus we found the PCQ to have high levels of reliability in both respects measured here: it was indeed measuring domains of child development, parenting capacity and family and environmental factors; and it was making those measurements consistently. A statistical note on Reliability (miss this out if you don’t like stats!!) We measured ‘internal coherence’ - the extent to which these were indeed measures of (latent) constructs of Child Development, Parenting Capacity and Family and Environmental factors – by the use of Chronbach’s alpha. We found this yielded the following (satisfactory) results Child Development: Parenting Capacity: Family and Environmental factors: 0.89 0.79 0.79 We measured consistency intraclass correlation, for which the results were PCQ as a whole Child Development: Parenting Capacity: Family and Environmental Factors 0.98 0.98 0.96 0.94 Conclusion Overall, therefore, we are able to show the PCQ is an instrument that ‘does what it says it does’. There is a clear rationale for its development; it does indeed provide a measurement of child welfare; and it does make these measurements consistently (hence it is reliable and valid). There is no doubt there is more that can be done with the PCQ. We can look for further measures of validity, with other instruments. We can see how it operates in different settings. Indeed the more we are able to use it and make appropriate tests, the more evidence we will have in support of its use, and its appropriateness to various settings. Nevertheless, we already have clear evidence in its support, as the only instrument with reliability and validity of use as a generic measure for children’s social care. Further reading on its reliability and validity Sheppard, M. (2010) ‘The Parent Concerns Questionnaire: A Reliable and Valid Common Assessment Framework for Child and Family Social Care’, British Journal of Social Work, 40, 2, pp 371-391 Sheppard, M., McDonald, P. and Welbourne, P. (2010) ‘The Parent Concerns Questionnaire and Parenting Stress Index: comparison of two Common Assessment Framework-compatible assessment instruments’, Child and Family Social Work, 15, 3, pp 345-56 NOTE We should be aware that the PCQ is a reliable and valid measure of parents’ perceptions of child welfare problems. In areas of practice liable to involve conflicts of perspective between practitioner and parent, and the danger of serious harm to a child, this will be reflected in the PCQ. This may be apparent in some cases involving child protection, where child protection plans (or the old child protection register) are involved. Where practitioners find it necessary to invoke legal powers in cases where parents pay insufficient regard to the dangers of significant harm to the child, we may expect those differences in perspective, where they occur, to be apparent in the PCQ Of course, the PCQ can be of use in these circumstances, since it will make clear exactly how the parent sees the child’s welfare, and enable the practitioner to work with parents in the light of the ways in which this differs from their (and their agency’s views) This is, of course an issue related to child protection. The conventional qualities of the PCQ as a needs assessment and outcome evaluation tool, both at individual and service level, are apparent where additional needs and family support come to the fore – very much the terrain of the Common Assessment Framework going right up to and including vulnerable high need families (as is apparent in some of the individual case example descriptions provided elsewhere on this web site). [See following page for references] REFERENCES Anastasi, A. and Urbina, S. (1997) Psychological Testing (seventh edition), Prentice hall, New Jersey, p 143 state ‘How high should a validity coefficient be? No general answer to this question is possible, since the interpretation of validity coefficient must take into account a number of concomitant circumstances [although]…the obtained correlation, of course, should be high enough to be statistically significant’. Department Of Health (2000) Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families, London, Stationery Office DfES (Department for Education and Skills) (2005) Common Assessment Framework for Children and Young People: Guide for Service Managers and Practitioners, London, Stationery Office Kaplan, RM and Saccuzzo, DP (1997) Psychological Testing, 4th edition, Brooks Cole,, London state, on page 135 ‘In practice one rarely sees a validity coefficient of larger than 0.6 and validity coefficients in the range of 0.3 to 0.4 are commonly considered high’. Sheppard, M. (2010) ‘The Parent Concerns Questionnaire: A Reliable and Valid Common Assessment Framework for Child and Family Social Care’, British Journal of Social Work, 40, 2, pp 371-391 Sheppard, M., McDonald, P. and Welbourne, P. (2010) ‘The Parent Concerns Questionnaire and Parenting Stress Index: comparison of two Common Assessment Framework-compatible assessment instruments’, Child and Family Social Work, 15, 3, pp 345-56 Sheppard, M. and Woodcock, J. (1999) ‘Need as an operating concept: the case of social work with children and families’, Child and Family Social Work, 4, 1, pp 67-77 Zielinsky, D. (2006) ‘Ecological Influences on the Sequelae of Child Maltreatment: A Review of the Literature’, Child Maltreatment, 11, 1, pp 49-62