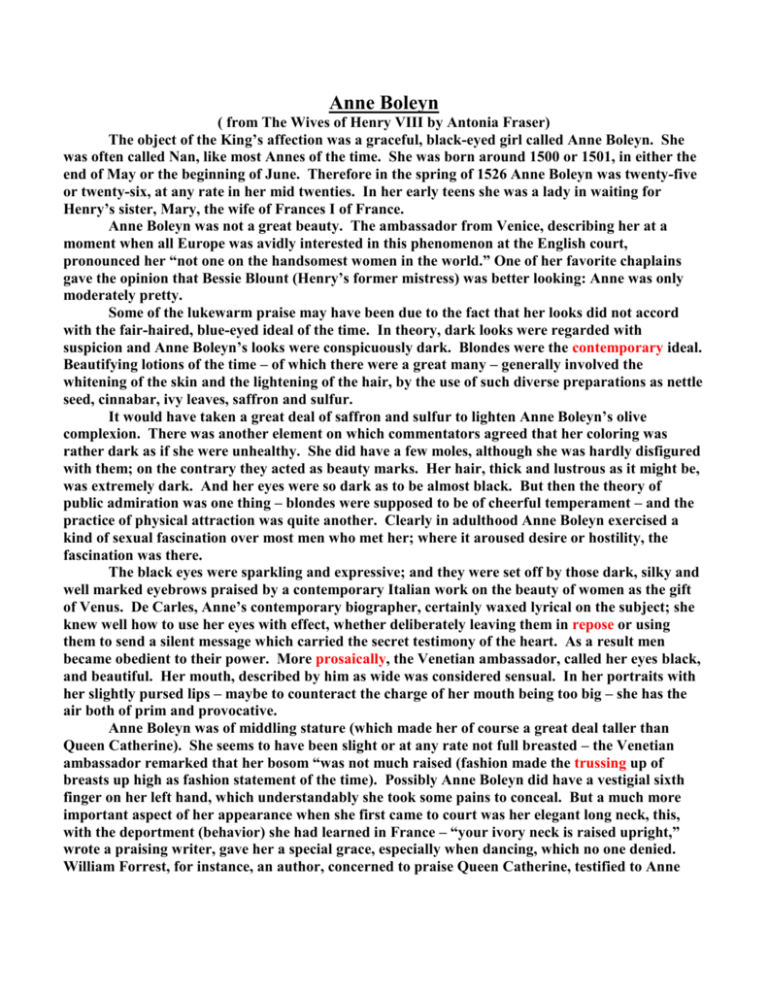

Anne Boleyn

( from The Wives of Henry VIII by Antonia Fraser)

The object of the King’s affection was a graceful, black-eyed girl called Anne Boleyn. She

was often called Nan, like most Annes of the time. She was born around 1500 or 1501, in either the

end of May or the beginning of June. Therefore in the spring of 1526 Anne Boleyn was twenty-five

or twenty-six, at any rate in her mid twenties. In her early teens she was a lady in waiting for

Henry’s sister, Mary, the wife of Frances I of France.

Anne Boleyn was not a great beauty. The ambassador from Venice, describing her at a

moment when all Europe was avidly interested in this phenomenon at the English court,

pronounced her “not one on the handsomest women in the world.” One of her favorite chaplains

gave the opinion that Bessie Blount (Henry’s former mistress) was better looking: Anne was only

moderately pretty.

Some of the lukewarm praise may have been due to the fact that her looks did not accord

with the fair-haired, blue-eyed ideal of the time. In theory, dark looks were regarded with

suspicion and Anne Boleyn’s looks were conspicuously dark. Blondes were the contemporary ideal.

Beautifying lotions of the time – of which there were a great many – generally involved the

whitening of the skin and the lightening of the hair, by the use of such diverse preparations as nettle

seed, cinnabar, ivy leaves, saffron and sulfur.

It would have taken a great deal of saffron and sulfur to lighten Anne Boleyn’s olive

complexion. There was another element on which commentators agreed that her coloring was

rather dark as if she were unhealthy. She did have a few moles, although she was hardly disfigured

with them; on the contrary they acted as beauty marks. Her hair, thick and lustrous as it might be,

was extremely dark. And her eyes were so dark as to be almost black. But then the theory of

public admiration was one thing – blondes were supposed to be of cheerful temperament – and the

practice of physical attraction was quite another. Clearly in adulthood Anne Boleyn exercised a

kind of sexual fascination over most men who met her; where it aroused desire or hostility, the

fascination was there.

The black eyes were sparkling and expressive; and they were set off by those dark, silky and

well marked eyebrows praised by a contemporary Italian work on the beauty of women as the gift

of Venus. De Carles, Anne’s contemporary biographer, certainly waxed lyrical on the subject; she

knew well how to use her eyes with effect, whether deliberately leaving them in repose or using

them to send a silent message which carried the secret testimony of the heart. As a result men

became obedient to their power. More prosaically, the Venetian ambassador, called her eyes black,

and beautiful. Her mouth, described by him as wide was considered sensual. In her portraits with

her slightly pursed lips – maybe to counteract the charge of her mouth being too big – she has the

air both of prim and provocative.

Anne Boleyn was of middling stature (which made her of course a great deal taller than

Queen Catherine). She seems to have been slight or at any rate not full breasted – the Venetian

ambassador remarked that her bosom “was not much raised (fashion made the trussing up of

breasts up high as fashion statement of the time). Possibly Anne Boleyn did have a vestigial sixth

finger on her left hand, which understandably she took some pains to conceal. But a much more

important aspect of her appearance when she first came to court was her elegant long neck, this,

with the deportment (behavior) she had learned in France – “your ivory neck is raised upright,”

wrote a praising writer, gave her a special grace, especially when dancing, which no one denied.

William Forrest, for instance, an author, concerned to praise Queen Catherine, testified to Anne

Boleyn’s passing excellent skill at the dance (so important in Henry VIII’s court), and also to her

pretty singing voice. In short; “here was a fresh young damsel that could trip and go.”

The fresh young damsel had other qualities, some more obvious than others at the moment

of her arrival in England. She had a very good wit. She was intelligent and full of spirit and

adventurousness; in other words, Anne Boleyn was good company. Like many spirited people, she

had another more impatient side to her; she would display on occasion a quick temper and a sharp

tongue. But of these characteristics, deplored in a woman as much as skill as singing and dancing

was prized, there was as yet no sign.

The King’s love of Anne Boleyn started with great suddenness, most probably around

March in 1526. That was the nature of the man. Anne had been a lady in waiting for the queen

when she caught the king’s eye. He was now in his thirty-fifth year – a dangerous age, it might be

thought - and had been on the throne for seventeen years, one-half of his life. But although middle

aged by the standards of the time, the King remained capable of boyish enthusiasm or what he at

least felt to be boyish desire. He was still energetic, still handsome, his build still athletic rather

than corpulent of his later years. A miniature of Henry VIII printed at this time showed a new

pudginess in the features, and no doubt his hat concealed a receding hairline. However, even five

years later, he would be described as having “a face like an angel (even if his head was by now

bald); you never saw a taller or more noble looking personage, wrote an observer.”

Yet for all Henry’s vigor, he no longer bore any real relation to the youth who had fallen in

love with Catherine of Aragon. That Henry had long ago vanished – except perhaps in the Queen’s

tender memories. Here was a confident and at times ruthless sovereign, who regarded it as his

natural right to have his own way in all things, and did not appreciate it when obstacles appeared in

his path. He was inclined to deal harshly with those – male or female – who he perceived as having

placed those obstacles in his way.

The violence of Henry’s VIII’s passion for his wife’s lady in waiting is attested by the

sequence of love letters that he wrote to her. All are handwritten. Indeed, their very existence is a

proof of passion, since the King greatly disliked writing letters and very few other handwritten

letters of his have survived with few exceptions. But Anne’s absence from court from time to time,

for a variety of reasons, proved intolerable and drove him to his pen.

There are seventeen letters altogether; none of them are dated. . . These are the letters of a

lover who aspires to his mistress’s favors – the word did not then necessarily have a sexual

connotation, rather a courtly one – but has not received them; the pleas of a suitor. In a letter

written when Henry had, by his own account, been “for more than a year, struck with the dart of

love.” He pleads to her to let him know her true intentions towards him. “I will take you for my

only mistress, casting out all competitors and serving only you.”

But Anne Boleyn, was not to be another Bessie Blount, let alone another Mary Boleyn,

quickly seduced, then married off to someone else. . . At some time before May 1527, the King had

decided that it was God’s will that he should have, as it were, a second chance in life. His

conscience told him that he should get rid of his first wife (to whom Henry stated he had never

really been married) and procreate a new family with the aid of a “fresh young damsel.” Henry

needed an annulment from Rome stating that he had never been married to Catherine in 1509.

This turn of events would have drastic effects on England for centuries to come.

12 paragraphs – 12 sentences (36 points)/ 8 vocab words (16 points)