The Economic Analysis of the State

advertisement

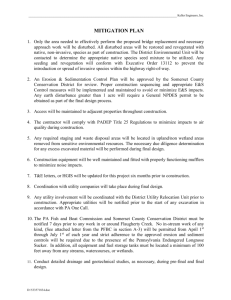

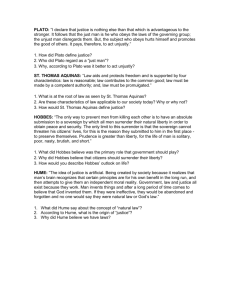

2. What objectives should the state pursue? Political philosophy has been examining this normative question since antiquity. So far, the question has not been definitively answered, and political philosophy continues to be an area of lively research. From this research has emerged a number of different approaches to the question, and it is important to understand these philosophical approaches so as to better understand how Economics relates to these older traditions. The earliest of these traditions in political philosophy has come to be known as Perfectionism. The Western roots of this tradition trace back to Ancient Greece and the political theories of Plato and Aristotle. Following Plato and Aristotle, all versions of perfectionism begin with an account of the ‘good life’ in which people live in harmony with what is central and essential to human nature. For Plato and Aristotle, this was a life of Eudaimonia (or human flourishing) within which virtue and the pursuit of knowledge were essential to the good life. On this basis, they advocated for a state that uses its power to promote privileged virtues and discourage harmful vice so that people might live ‘the good life’. By encouraging everyone to live the best life possible, the state will have succeeded in creating ‘the good society’. In ‘The Republic’ (c. 360 B.C.), Plato argued that such a ‘good society’ could be best brought into being by a philosopher King.1 He also argued that private property should be replaced with collective property so as to eliminate conflicting private interests and to promote the pursuit of common interests. It should be noted that Plato was writing just after the terrible defeat of democratic Athens by Sparta and her allies. In the aftermath of this defeat, Socrates (Plato’s teacher) went to some effort to point out the moral weaknesses of Athenian society and the strength of Spartan society. The citizens of Athens did not respond well to such criticism, convicting him of corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, for which he was put to death in 399 B.C. Plato’s repudiation of democracy was famously challenged by Aristotle. In “Politics” (c. 323 B.C.), Aristotle suggests that while a monarchy might be the ideal form of government, the best practical form of government might well be a polity in which a mixed constitution combines the institutions of democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy with the rule of law. Interestingly, he is very critical of Plato’s conception of the ideal society because he argued Plato erred in overvaluing political unity and in promoting an impractical system of communal ownership.2 Instead he argued that private ownership promotes private virtues such as responsibility and prudence and a necessary sense of self possession that is at the root of freedom and citizenship. Furthermore he argued that private property discourages social conflicts because “When everyone has a distinct interest, men will not complain to one another, and they will make more progress, 1 "Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophise, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils,... nor, I think, will the human race." (Republic 473c-d) In “The Open Society and It’s Enemies” (1945), Karl Popper advanced the idea that Plato’s Republic provided a prestigious foundation for promotion of the Utopian Authoritarianism found in Fascism and Communism. 2 because everyone will be attending to his own business” (Aristotle 1988 [c. 330 BCE, 1263a]. Subsequent Christian philosophers who worked from this perfectionist tradition saw the good life to be one which was lived according to the will of God. Once again, the purpose of the state was to promote privileged virtues and discourage harmful vices so that people might better live in harmony with their true god-given nature and avoid the temptations of a life lived in disobedience to divine will. In Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ (1516 AD), the ideal society is presented as a form of democratic socialism in which property has been eliminated – with the notable exception that every household owns two slaves. From Christian Perfectionism also comes the anti-democratic doctrine of the ‘Divine Right of Kings’ wherein divine will and true human nature combine to justify the authority of an Absolute Monarch as the sovereign authority of the state.3 In the 20th Century, Christian Perfectionism provided the foundation for both social democracy and fascism and their contradictory claims about how to bring forth ‘the good society’ in which people can live in harmony with their better nature and the will of God. By the 17th Century, the nation state headed by an absolute monarch seemed well on its way to becoming the dominant political order in continental Europe. In contrast, Britain was undergoing a period of sustained political and intellectual upheaval, culminating in the British civil wars. The conflict centered on a disagreement between those that believed the sovereign authority of the state resided in the court of the King and those that supported the view that the sovereign authority of the state resided in Parliament. In the Leviathan (1651), Thomas Hobbes managed to alienate both sides in this conflict by defending the absolute authority of the King, but by denying the divine origin of this authority. Instead he argued that the origin of the sovereign’s authority lay in a social contract. As we have already discussed, Hobbes argued that people in a state of nature would chose to surrender their freedom and submit to the law and the ethical norms established by a sovereign power in order that a more peaceful and prosperous society becomes possible. Hobbes went on to argue that under the social contract, the sovereign had an absolute right to determine what objectives the state should pursue and an absolute right dispose of the power of the state in any way he saw fit. While Hobbes’ conclusions regarding the authority of the King utterly failed to resolve the conflict between Parliament and the King, it did succeed in creating a whole new approach to political and moral philosophy. One branch of this new approach has come to be known as Contractarianism. While there is great diversity of contractarian theories of the state, all share in the claim that legitimate authority of sovereign must derive from the consent of the governed in the form of a mutually agreed social contract. Furthermore, Contractarians argue that the legal statutes and moral norms that issue from the state derive their legitimacy from the mutually agreed social contract. John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau famously disputed Hobbes’ position concerning the rights of the sovereign given by the social contract. Instead they argued that the sovereign’s right derived from the common good provided by the social contract. 3 John Locke singled out Robert Filmer's Patriarcha, or the Natural Power of Kings, (1680) as the most comprehensive and accomplished expression of the Divine Right of Kings. Any action by the sovereign that harmed the common good was viewed as a tyrannical departure from the social contract. In such instances, individual subjects of the sovereign were then freed from the obligations of the social contract and had the right of rebellion. In other words, the social contract required the sovereign to actively seek the ongoing consent of the governed. For Locke, this suggested that the exercise of sovereign authority must rest with an elected assembly. Rousseau concluded that sovereign authority must be guided by “the general will”, but is vague about how this would operate. What emerges from Locke and Rousseau’s Contractarianism is the notion that a central objective of the state is to provide its citizens with popular sovereignty and fundamental rights and freedoms. The U.S. Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen both stemmed directly from the work of Locke and Rousseau respectively. This line of thinking about the state has continued into the modern world, forming an important foundation for the development of liberal democracy and human rights. Modern contractarian thinking continues to develop and be renewed within the work of political and moral philosophers to this day.4 Much of the modern focus is on what fundamental rights and duties should be created and supported by the state. While economists were strongly influenced by the rise of liberal political thought built upon this Contractarian foundation, the idea of a social contract has not been essential to economic thinking about the state and its proper objectives. 5 Instead, economic analysis of the state builds on Hobbes’ idea that the coercive power of the state has the functional purpose of making peace and prosperity possible. From this idea, economists and philosophers have developed a second new approach to Political and Moral philosophy which has come to be known as Consequentialism. Under Consequentialism, there is no need to appeal to a social contract or to any ideal notion of authentic human nature to justify the coercive power of the state or discover the proper objectives of the state. Instead, the state is seen to be a social institution that can use its power to functionally influence social outcomes. The proper objective of the state is the use of this power in the pursuit of desired social consequences. From this view, all actions by the state are therefore justified by expedience in the pursuit of these desired social consequences. For instance John Rawls’ “A Theory of Justice” (1972) has extended Kant’s categorical imperative into a new contractarian (contractualism) logic for the state. More recently, David Gauthier’s “Morals By Agreement” (1986) re-examines and renews Hobbes’ social contract using formal game theory arguments like the one we examined in the last chapter. Mention of Kant’s Deontological theories …. 4 While Adam Smith was certainly influenced by Hobbes’ view that the sovereign power of the state is necessary to create the conditions necessary for the market to operate successfully, he did not deem it necessary to adopt a position on what man’s condition was in a state of nature, nor did he find it important to examine whether a social contract existed. 5 In Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith developed this new understanding that the state served a functional purpose to show that the level of prosperity can depend in unexpected ways on the choices that a state makes. For instance, in a modern state, peace and prosperity are built from a huge web of cooperative actions by a great many people who usually do not know one another. He argued that this cooperation was neither driven by altruistic concern for one’s neighbor, nor by a sense of duty or right. Instead, egoistic concern over one’s own interests is often at the root of much of this cooperative social action. “Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages. Nobody but a beggar chuses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens. Even a beggar does not depend upon it entirely.” An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book 1, Chapter 2 in paragraph I.2.2, Adam Smith Fifth edition (1789). The implication is radical. If prosperity is considered a desirable social consequence, then the sovereign had a very definite obligation to use the power of the state to encourage commerce, or at the very least, stop doing things which discouraged commerce. Furthermore, Perfectionism’s central concern with having the state promote altruism and other virtues is seen by Smith as a distraction from what the state can and should be focused on achieving.6 The Contractarian concern with the state providing popular sovereignty and fundamental rights and freedoms reduces to a question of expedience under Consequentialism - popular sovereignty and rights and freedoms if they increase prosperity. By the early 19th Century, the British Industrial Revolution presented an unusual set of problems that showed that a focus on national prosperity alone could lead to serious social problems. One worry was that prosperity carried with it, the seeds of its own destruction. First Robert Malthus provided a long run analysis of how general prosperity would lead to higher birth rates and a falling wage rate, dooming the vast majority of society to a life of bare subsistence. Later, Karl Marx provided a worrying long run analysis of how capital accumulation would eventually cause the rate of profit to fall, and that this would create stagnation and an unavoidable crisis in market capitalism. 6 Smith did believe that human beings benefited from living an ethical life based on virtuous conduct. He simply felt that the state’s central concern was not to direct people towards living the good life. Today, Perfectionism, Contractarianism and Consequentialism are all still very much alive. The differences between their different concepts of the good society are often at the root of many arguments about what the state can and should do. For instance, entrepreneurs in British Columbian have developed a highly profitable cannabis industry that is illegal because of concerns about the personal and social impact of cannabis use. Even without these potential long run catastrophes, more immediate problems with prosperity were becoming increasingly difficult for 19th Century political economists to ignore. Extreme inequality and poverty seemed to accompany the rising national prosperity that followed from the industrial revolution. In addition, the single minded pursuit of national prosperity was also creating smog in the new cities and the destruction of natural habitat in the countryside. Finally, the working conditions of the new urban working class were abysmal. Long hours, poor pay and repetitive tasks diminished the meaningfulness of work. For many political economists, the rising national prosperity was not bringing forth the hoped for good society. Because of these unwanted social developments, it seemed increasingly important that the state use its power to pursue more than national prosperity and consider a broadened list of social objectives that included an increase in: distributive justice; environmental quality; individual liberty; community solidarity; scientific knowledge; individual virtue; artistic achievement; etc. Unfortunately, such an expanded list of social objectives presents several dilemmas. The first is whether state action will help or hinder society in achieving progressive improvements in these objectives. Even if appropriate state action can be found to promote these objectives, there remains the troubling problem that progressive improvement of one social objective, often requires sacrificing other social objectives. For instance, if the state chooses to reduce inequality and increase distributive justice, it might choose to use income taxes and government transfers to redistribute income. While this can be effective at redistributing income, it is common for economists to point out that there are social costs that should not be ignored. Higher taxes reduce the incentive to work, invest, and innovate and hence reduce future prosperity. Such policies also changes individual liberty in a complicated way. On the one hand, redistribution reduces negative liberty (freedom from restraint) for tax payers; but on the other hand, it increases positive liberty (opportunity and ability to act to fulfill one's own potential) for those receiving transfers. It is easy to see that tradeoffs seem to be endemic to social action by the state. Jeremy Bentham proposed that social choices in a world with such tradeoffs between social goods could be made by reference to some ultimate social good. Following the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus, Bentham proposed that human pleasure and pain were the only intrinsic values in the world. Additions to pleasure and reduction in pain increased individual happiness and Bentham argued that the state’s proper objective was to choose policies that provided the greatest happiness. Under subsequent writers, the idea that pleasure and pain were the only intrinsic values in the world was stretched to include all sources of ‘satisfaction’ – referred to as utility – as the source of intrinsic value. From this John Stuart Mill coined the term Utilitarianism for the Political and Moral philosophy that the social good is determined by total utility. Under Utilitarianism, conflicts between desired social consequences reduce to the problem of finding policies that maximize total utility. For many Classical Economists in early 19th Century Britain, Utilitarianism became very influential, leading many economists to promote a liberal reform agenda that emphasized: free trade, extension of the franchise (right to vote), increase in personal liberty, end to slavery, and many other issues that many modern economists might view as being outside of the economic sphere of expertise. To get a sense of how Utilitarian logic operates in situations where difficult social tradeoffs exist, consider the following model of utility. Suppose that utility increases as the amount of money increases, but that it increases at a decreasing rate. If we were to represent this as a function, we would have utility (u) as a concave function (U) of money (m), where u = U(m), and U’>0 and U’’<0. Such a function might look like figure 2.1. Figure 2.1 u U(m) m (in $1,000’s) 0 50 100 Suppose that $20,000 was taken from a person with $100,000 dollars and given to a person with $10,000. If each person has the utility function as illustrated in figure 1, the loss in utility of the rich donor is less than the gain in utility of the poor recipient. The result is that total utility must have increased. Of course, any such redistribution is likely to change the incentives for both the poor and rich person, and this may create a substantial cost to total utility. The optimal utilitarian policy would be one which balanced the gain in utility from redistribution with the loss in utility from the alteration in market incentives that such redistribution is likely to incur.7 An obvious problem with this model is that it uses the simplifying assumption that the rich person and the poor person share the same utility function. This assumption can be relaxed, with each person having a different utility of money function. So long as the poor person has a larger marginal utility of money function than the rich person (which 7 Edgeworth (1897), "The Pure Theory of Taxation: Parts I, II and III", EJ seems to be more likely the larger the difference in income), then the utilitarian justification for inequality reducing transfers from rich to poor is easily demonstrated. A less obvious problem is revealed when you consider two people with exactly the same income, but different utility of money functions. The optimal Utilitarian policy is to transfer money from the person with the lower marginal utility of money to the person with the higher marginal utility of money. This seems to suggest that Utilitarians advocate increasing inequality by rewarding people with money loving preferences, as the money lovers will make “better use” of the money than other people. This peculiar outcome highlights a problem with Utilitarianism that moral philosophers have delighted in pointed out – that Utilitarian policy and ethical rules can be easily found that seem intuitively at odds with living the good life or supporting the good society. The main alternative to Utilitarianism and other forms of Consequentialism is Deontology. While a Utilitarian (and all Consequentialists) would determine whether an action is right according to the goodness of the outcome from the action, a Deontologist would determine whether an action is right according to the rightness or wrongness of the actions themselves.8 When it comes to government policy, Deontological political and moral philosophy tends to lead to a policy discourse based on rights and responsibilities. As John Stuart Mill pointed out, such a discourse has difficulty when rights conflict or when duties conflict, or when rights and duties conflict. Without adopting some form of Consequentialism, it is difficult to sort through the competing claims and arrive at what principle has priority. Given that public policy is fraught with such conflicts, it is not surprising that early economists gravitated towards Utilitarianism. The pragmatic appeal of Utilitarianism began to wane towards the end of the 19th Century as it became increasingly apparent that there were too many practical problems that could not be overcome with the emerging tools of social science. In particular, Jeremy Bentham’s proposal that a felicific calculus be used to add up the pleasure and pain caused by a proposed change in government policy so as to determine whether the policy change increased or decreased total happiness, did not enter into the toolkit of economic analysis for a number of very good reasons. First of all, John Stuart Mill pointed out that simple hedonic measures of pain and pleasure are not commensurate with cultural, intellectual, and spiritual pleasures. Given the low level of education of the general population, Mill was concerned that a simple addition of pleasure would tend to cause the state to promote policies that met base desires (for instance cheap gin) that were at odds with progress and its reward of higher order pleasures and a deeper happiness. In a similar line of reasoning, some have voiced concern that those with sadistic preferences pose a special problem for the felicific calculus. A second serious problem with utilitarianism is that there are no precise techniques for measuring and comparing the pleasure, pain, happiness, satisfaction, or utility of very different people. By the beginning of the 20th Century, utility began to be viewed as a fundamentally subjective value that was resistive to measurement. Finally, even if the measurement problem could be overcome, the difficulty of accurately predicting the 8 Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative is perhaps the most famous alternative to the impact of a policy on total utility made the whole project somewhat suspect - especially when the policy introduces something new to society. With the failure of Utilitarianism, doubt arose about whether Economics had anything at all to say about what the state should be doing. Fortunately for economists that study the state, a new path was discovered in the ‘New Welfare Economics’. The essential elements of this new path was the development of new tools based on Pareto Efficiency, the Kaldor-Hicks compensation tests, cardinal social welfare functions, and the axiomatic measurement of living standards, poverty, inequality and other measures of distribution. This opened the door for economists to advise governments on how they might most efficiently meet social objectives. Unlike Utilitarian Economics, the New Welfare Economics did not provide economists with the tools for examining what the final social objectives the state should pursue. These have tended to be viewed by many economists as being outside of Economic analysis, and more properly a subject for philosophical and political debate. To better understand how this shift from Utilitarianism to the New Welfare Economics has changed how economists contribute to the debate over what government should be doing, consider the question of redistribution considered earlier under the Utilitarian framework. The New Welfare Economics has provided a number of new tools for measuring poverty and inequality and new tools for measuring the efficiency cost of a various tax and transfer system. While the New Welfare Economics can offer guidance to political decision-makers about the effectiveness of alternative redistributive schemes in reducing poverty and inequality and the efficiency costs of these alternatives, it cannot pretend to offer advice on what is the optimal balance in the trade-off between the efficiency cost and the social justice benefit from a social policy intervention aimed at poverty alleviation and inequality reduction. Notice that while the boundaries for economic analysis of normative questions are limited, the logic governing this normative analysis is still firmly rooted within Consequentialism. The question of “what objectives should the state pursue” is a decidedly normative question that struggles with measuring social value. The approach taken by the new welfare economics has not been satisfying to many economists who wish to see Economics constructed on a more scientific foundation. Out of this dissatisfaction has grown an alternative approach to the economics of the state that attempts to set aside normative questions entirely. Instead, many economists have focused on the positive question of what objectives the state actually pursues. Specifically, economists began to wonder whether the state might benefit from the same sort of examination that economists had made of the institutions of the family and firms. Economists had made great progress in examining how the family’s objective to maximize its satisfaction (utility) interacts with the family’s constraints to create market demand and the supply of labor and financial capital. Economists had also made great progress in discovering how the profit maximizing objectives of firms interacted with its technological constraints, factor prices and market structure to generate the market supply of commodities and services. The natural question that emerged was whether a similar sort of examination might help economists better understand the behavior of governments. Public Choice Economics emerged in the second half of the 20th Century as a way of trying to understand how state actions were influenced by the constraints facing the state and the private interests of politicians, bureaucrats, voters and other state actors. This research has dramatically changed how economists view the objectives the state pursues away from the traditional normative focus, to a positive focus on developing a better understanding of the often peculiar behavior of the state. We will have more to say about this in future chapters. Glossary: Anarchism Contractarianism Consequentialism Deep Ecology Distributive Justice Expedience Fascism Laissez-Faire Leviathan Normative Statement Opportunity Cost Polis Positive Statement Social Contract Socialism Utilitarianism Wealth of Nations References: Problems: