Geol 2033 Mineralogy and Petrology

advertisement

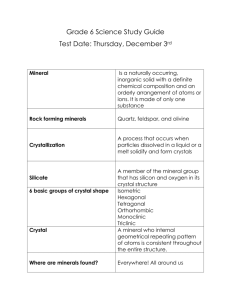

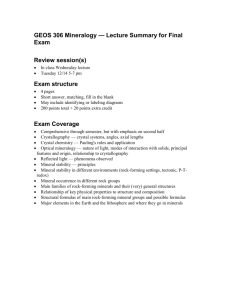

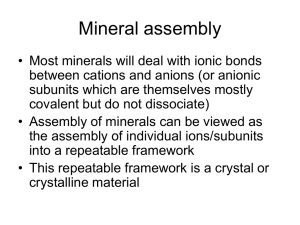

Geol 2033 Mineralogy and Petrology Lecture 1 Outline and grading procedure - handout Begin with minerals. Minerals are the chemical compounds of the earth - the basic ingredients of geologic materials, though of course divisible into atoms of different elements and into sub-atomic units. Minerals are important to all fields of geology. They are the source of many resources iron, copper, gold, gypsum, sand. Rocks are composed of and identified by the minerals contained. Soils are largely mineral, and the nutrients and pollutants in soils are attached to the mineral particles. Used to spend a year in mineralogy courses studying perhaps 200 minerals. We now concentrate on less than 100 in this course and you will learn others as you need to in other courses. Definition of MINERAL page 1 K&H and overhead A MINERAL IS - A NATURALLY OCCURRING HOMOGENEOUS SOLID - with a DEFINITE (BUT NOT FIXED) CHEMICAL COMPOSITION - A HIGHLY ORDERED ATOMIC ARRANGEMENT It is usually FORMED BY INORGANIC PROCESSES This definition, followed strictly, would include water in the form of ice as a mineral; but not liquid water. Similarly, liquid mercury, which occurs in some mercury deposits is not strictly a mineral, and the term mineraloid is applied. The composition of some minerals, such as quartz (SiO2), pyrite (FeS2), and halite (NaCl) is virtually constant - they have a fixed chemical composition. Most minerals, however, display some variation in composition. The fomula of the black mica, biotite, is usually expressed as K(Mg,Fe)3(AlSi3O10)(OH)2 because the amounts of magnesium and iron vary from place to place, but the sum of the two (ionic amounts) relative to other elements is constant. The proportions of the other elements are essentially constant. Thus we describe the composition as definite but not fixed. Some formulas can be very long - tourmaline, for example, which has multiple substitutions! (Na,Ca)(Li,Mg,Al,)(Al,Fe,Mn)6(BO3)3(Si6O18)(OH)4 ------We will begin our study of minerals by looking at the physical properties that are used to identify them, starting with their crystal shape. A crystal is a homogeneous solid, possessing long-range, three-dimensional internal order. We can't see this internal order, except by X-ray, electron microscope and other techniques. We can, however, find specimens of minerals that are bounded by crystal faces ("good crystals") and the science of crystallography was based on observations of the external form of crystals until the beginning of this century, when X-rays were discovered. The following terms ( p. 17 KH) describe the extent to which crystal faces are present in a mineral specimen - euhedral , subhedral, anhedral Comparison of crystals of the same mineral show that they have similar faces with similar angles between them. In 1669 Niels Stensen (known by the latinized version of his name Nicolaus Steno - made the generalization that The angles between equivalent faces of crystals of the same substance measured at the same temperature, are constant Steno's law. (p. 35KH) Study of many crystals shows that they can be grouped into six basically different systems. These are defined on page 38 of KH SHOW SYSTEM MODELS AND HAND OUT SHEETS Crystal systems ISOMETRIC TETRAGONAL ORTHORHOMBIC MONOCLINIC TRICLINIC HEXAGONAL Natural crystals are seldom perfectly shaped so we will use plastic and wooden models to illustrate crystal shapes, but use natural crystals as much as possible to show that they really exist. HAND OUT - CRYSTAL HUNT