The Jungle: Upton Sinclair & Food Safety Reform

advertisement

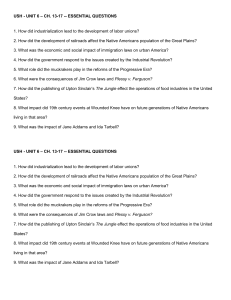

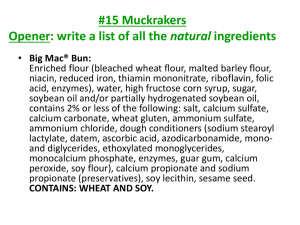

1906: Uproar from “The Jungle” NY Times Upfront Magazine Sept. 19, 2005 There is a story that President Theodore Roosevelt came to breakfast at the White House one morning in 1906, carrying a new novel called The Jungle. Once seated, the President picked up where he had left off, reading along while eating his usual hearty meal, when suddenly he looked down in disgust at the sausage on his plate, carried it to the window, and threw it out onto the White House lawn. The story, invented by the humorist Finley Peter Dunne became one of the first nationally syndicated newspaper features. , perfectly captured the entire country's reaction to The Jungle, which was published 100 years ago this winter. It was an instant best-seller, and it caused millions of people to look at a lot of what they were eating with alarm and disgust. The book's author, an unknown and impoverished 27-year-old named Upton Sinclair, then living on a farm in Princeton, N.J., became an overnight celebrity. The Jungle follows the rapid decline of Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian immigrant who arrives in Chicago and goes to work in Packingtown, where the giant "Beef Trust" has its slaughterhouses and meatpacking or meat-processing, wholesale business of buying and slaughtering animals and then processing and distributing their carcasses to retailers. The livestock industry is among the largest in the world. Conditions there are brutal for workers like Jurgis and his wife, Ona. In just a few years, Jurgis watches helplessly as his wife and their two children die, while he becomes a vagrant, a thief, and an alcoholic. Only at the conclusion does hope return, when Jurgis is inspired by the speech of a Socialist activist and resolves to fight the capitalist system that he thinks has destroyed him. GRISLY SCENES Not everyone liked the book. The New York Times ran a largely negative review in March 1906. The reviewer said it was "in many ways a brilliant study of the great industries of Chicago," and of the workers' "fierce struggle for work, for wages, and for life." However, he said, the book was more propaganda than art. But The Jungle owed its success less to its social criticism than to its graphic scenes of the huge slaughterhouses and meatpacking plants in Chicago. In real life, companies like Armour and Swift had a virtual monopoly on the processing of meat that the country put on its table. There are descriptions of men falling into great rendering vats, where their flesh and bones are quickly boiled and mixed with the meat being processed. Diseased animals are butchered and their meat prepared for sale, while deadly acids and dyes are injected into spoiled hams so they can be sold as sound. Some areas are virtually overrun by rats, whose droppings go into sausages along with their dead bodies. The list of horrors went on and on. Sinclair, who spent months in the real-life Packingtown gathering material, hadn't intended to write a book about food safety. He believed that The Jungle was primarily a denunciation of capitalism at the beginning of the 20th century, when the first giant American corporations took shape and often banded together in trusts to the activity of designing and constructing and operating railroads rail technology , tobacco, oil refining, steelmaking, and banking. What Sinclair wanted was for the country to abandon capitalism and turn instead to socialism. "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach," he wrote in 1960, disappointed that readers paid attention to the rotten food, and not the workers' struggles. A CHANGING NATION In fact, most Americans didn't want revolution, but they did want reform. It was the height of the Progressive Era, when there was deep anxiety, especially among the growing middle class, about how the nation was changing. Since the end of the Civil War in 1865, America had been transformed from a rural, agricultural country into an urban and industrial powerhouse. A small group of industrialists, household names like Andrew Carnegie and E.H. Harriman, earned great wealth by employing thousands of workers, many of them immigrants, in rough jobs for poor pay. These workers transformed cities with their new customs and languages, in densely populated slums that many native-born Americans found bewildering. Critics of this new America wanted to curtail the prevailing "laissez-faire" mentality in Washington that let the country and its economy develop with little government interference; they sought, instead, more government involvement in the nation's evolving economy and society. 'MUCKRAKERS' Writers like Sinclair spearheaded the Progressive reform movement. These were the "muckrakers"--President Roosevelt's term for a group of journalists and novelists, many of whom wrote for new mass-circulation magazines like Collier's and The Saturday Evening Post. Lincoln Steffens exposed the political corruption of city governments in Minneapolis, St. Louis, and elsewhere; Ida Tarbell showed how the Standard Oil Trust abused its power; Jacob Riis portrayed the misery of the New York City slums, writing and taking photographs (many of them staged) to tell his story. In the case of Sinclair, his muckraking novel, combined with the political climate and Roosevelt's own desire for action, spurred the passage in 1906 of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act, which led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration. These acts were the first enforceable national laws meant to ensure the safety of American food and medicine. In the same year, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), was strengthened to enable it to curb the power of the railroads. In 1913, Congress passed the Underwood Tariff Act, which instituted America's first tax on personal income. The liberal historian Carl Degler called the income tax a powerful reform symbol as the "equalizer of the great disparities of wealth" that came with the Industrial Age. HOW MUCH REGULATION? In 1914, the Federal Trade Commission was created as a watchdog over the business world. Many state governments also enacted reform measures, such as restricting the use of child labor, or the use of the young as workers in factories, farms, and mines. Child labor was first recognized as a social problem with the introduction of the factory system in late 18th-century Great Britain. . Eventually, the reforming energies of the Progressives waned, in part due to the onset of World War I and the economic boom of the Roaring Twenties, when many Americans became convinced they could get rich through the stock market. The muckrakers (even Sinclair, who died in 1968) became just a series of famous names from the past. In the 1970s, the government began focusing on "deregulation" in many areas, in response to concerns that too much regulation was stifling the nation's economic growth. But debate over questions raised by the muckrakers continues today, including how much government regulation--or interference, depending on your point of view--is necessary to safeguard citizens, workers, and the environment from the power of large corporations. Peter Edidin is an editor for the Week in Review section of The New York Times.