Contents

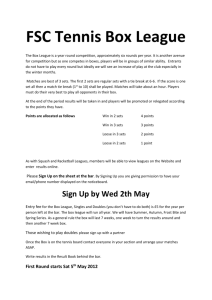

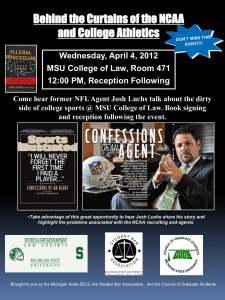

advertisement