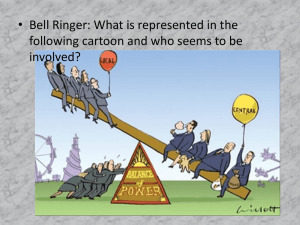

LECTURE NOTES - California State University, Long Beach

advertisement