The Existence of God - Thomas L. Forbes, Ed.D.

advertisement

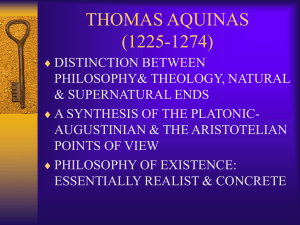

READING SUMMARY Read The Existence of God, briefly summarize in your own words each of Aquinas’ 5 proofs for the existence of God, and relate them to Neo-Scholasticism (see the text pages 50-58). Bring your typed summary to the next class meeting. The Existence of God From the Summa Theologica Part I (1266-1268) By Saint Thomas Aquinas Saint Thomas Aquinas was a leading theologian and philosopher during the so-called golden age of scholasticism in the 13th century. The following passage from his Summa Theologica provides a good example of the scholastic method, which began with a question, then assembled arguments on the question that were eventually reconciled. Aquinas draws upon many authorities for his discussion, ranging from 4th-century BC Greek philosopher Aristotle to Christian theologian Saint Augustine (AD 354-430). Does God Exist? Objections Objection 1. It seems that there is no God. For if one of two opposing entities were to exist without limitation the other would be totally destroyed. But the word, God, means something that is infinitely good. Therefore if there were a God, evil would not exist. But we encounter evil in the world. Therefore there is no God. Objection 2. Furthermore what can be explained by a few causes should not be explained by many. But it seems that everything we see in the world can be explained by other causes without assuming that God exists, because natural things are explained by natural causes, while those that are done for a purpose are the products of human reason and will. Therefore there is no need to suppose that God exists. On the contrary, God says in the Scripture, “I am who am.” I answer that the existence of God can be proved in five ways: The first and most obvious way is the argument from motion. It is certain and evident to our senses that things are in motion in this world. Everything that moves is moved by something else, for nothing can move unless it has the potentiality of acquiring the perfection of that towards which it moves. To move something is to act, since to move is to make actual what is potential. Now nothing can be changed from a state of potentiality to actuality except by something that itself is in a state of actuality. A fire that is actually hot makes wood that is potentially hot become actually hot, and so moves and changes it. Now it is impossible for the same thing to be both in actuality and in potentiality at the same time and in the same respect—only in different respects. What is actually hot cannot at the same time be potentially hot, although it is potentially cold. Therefore it is impossible for a thing to be both the mover and the thing moved in the same way, or for it to move itself. Therefore everything that moves must be moved by something else. If that by which it is moved also moves, it must itself be moved by something else and that by something else again. But things can not go on forever because then there would be no first mover, and consequently no subsequent mover since intermediate things move only from the motion they receive from the first mover—just as a staff moves only because it is moved by a hand. Therefore it is necessary to go back to some first mover who is not moved by anyone, and this everyone understands as God. The second way is from the nature of an efficient cause. In the world of the senses we find that there is a sequence of efficient causes, but we never find something that causes itself, and it is impossible to do because it would precede itself—which is impossible. Now the series of finite causes cannot go on to infinity because in every series of causes the first cause is the cause of the intermediate cause and intermediate causes cause the last cause, whether the intermediate causes are many or only one. However if you take away a cause you also take away its effect. If there is no first cause among the efficient causes, there will be no last or intermediate cause. But if we proceed to infinity in the series of causes there will be no first cause and therefore no final or intermediate effects would exist—which is obviously not true. Thus it is necessary to posit some first efficient cause which all men call God. The third way is based on what can exist (possibility) and what must exist (necessity). It is the following: We find things in nature that can exist or not exist, since things are found to come into existence (be generated) and to cease to exist (be corrupted) and therefore it is possible for them to exist or not exist. Now it is impossible for such things always to have existed, for if it is possible for something not to exist, at some time it did not exist. Therefore if it is possible for everything not to exist, at one time nothing was in existence. But if this is true then nothing would exist even now, since that which does not exist only begins to exist through something else that is in existence. But if nothing was in existence it was impossible for anything to begin to exist, and so nothing would exist now—which is obviously not true. Everything cannot be [merely] possible but there must be some necessary being in existence. Something is a necessary being either as a result of the action of another or not. However it is impossible to go on to infinity in [the series of] necessary beings that must exist because they are caused by another, as we have already proved above in the case of efficient causes. We must therefore posit a [necessary] being that must exist in itself and does not owe its existence to anything else, but is the reason that other things must be. This all men call God. The fourth way is based on the gradations that exist in things. We find in the world that some things are more or less true, or good, or noble and so on. The description of “more” or “less” is given to things to the degree that they approach the superlative in various ways. For example a thing is said to be hotter as it approaches more closely what is hottest. Therefore there is something that is the most true, and best, and most noble, and consequently most fully in being, for the things that are the greatest in truth are the greatest in being, as is said in the Metaphysics. Now the superlative in any classification (genus) is the cause of all the things in that classification. Fire, for example, which is the hottest of all things is the cause of everything that is hot, as is said in the same book. Therefore there is something that is the cause of being and goodness and whatever perfection everything has, and this we call God. The fifth way is based on the order (gobernatio) in the universe. We see that things that lack consciousness such as bodies in nature function purposively. This is evident from the fact that they always, or nearly always, function in the same way so as to achieve what is best. Therefore it is evident that they achieve their end, not by chance but by design. But things that do not possess consciousness tend towards an end only because they are directed by a being that possesses consciousness and intelligence, in the same way that an arrow must be aimed by an archer. Therefore there is an intelligent being who directs all things to their goal, and we say that this is God. Conclusion Reply to Objection. 1. Augustine says, “Since God is the supremely highest good he would not allow evil to exist in his creation unless he were so all powerful and good that he could even make good out of evil.” Thus it is part of the infinite goodness of God that he permits evils to exist so that he can bring good from them. Reply to Objection. 2. Since nature acts for a given end at the direction of a higher agent, the things that take place in nature go back to God as their first cause. Similarly what is done for a purpose must go back to some higher cause which is not the reason and will of man because these are changeable and can cease to exist. Everything that is changeable and perishable must go back to an unchangeable and necessary first cause that is unchangeable and self-existent (per se necessarium). Source St. Thomas Aquinas on Politics and Ethics, ed. Paul Sigmund. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1988.