Five Ways to show that God exists

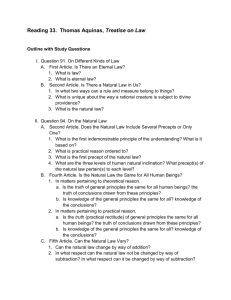

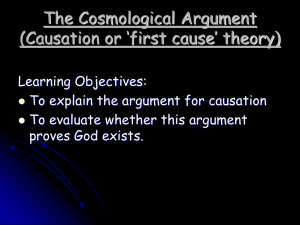

advertisement

St. Thomas Aquinas The Existence and Nature of God Thomas Aquinas Born in Roccasecca, Kingdom of Sicily, in 1224 or 25 and died at Fossanova, en route to the Council of Lyons in 1274. A theologian and professor of Sacred Scripture at the University of Paris, Thomas integrated the thought of Aristotle with Christian theology. Summa Theologiae Belief in God Everyone believes in God. The only question is who or what God is. Traditionally and historically What a god is A god is a superior, generally immortal kind of being, superior to human beings and exercising some sort of governance over a part of the natural order. As understood by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, God is the Supreme Being and Creator of all things. Human beings are ultimately responsible to him for their lives. Believing in God Every people of every age has worshipped God or gods. Religion and belief in something divine are ubiquitous. Atheism is not ‘natural,’ not the ‘default’ position of the human mind and heart. Mikhail Gorbachev said: “Well, I believe in the cosmos. All of us are linked to the cosmos. Look at the sun. If there is no sun, then we cannot exist. So nature is my god. To me, nature is sacred. Trees are my temples and forests are my cathedrals.” The contemporary discussion. Privatization of religion Belief in God is a personal thing, one’s own business. So the existence of God is a religious idea, but not an objective fact. Whether God is real and what God is cannot be known. Each person has to decide who God is for him or herself. Intellectual disrepute The intellectual’s stance: “orthodox agnosticism.” Laplace on God’s role in the scientific view of the universe: “Je n’ai pas besoin de cette hypothèse.” General hostility towards God’s inclusion in science and human affairs In sum: To believe in God is today considered a decision of the will and not legitimately the fruit of exercise of reason. So the question we ask ourselves is: ‘Is it reasonable to believe in God?’ Are there solid reasons for believing in God? Are there evidence and a chain of valid or plausible argumentation establishing that God exists? Summa Theologiae, q. 2: The existence of God Article 1: The alleged self-evidence of God’s existence Thomas first addresses himself to the devout belief that God is so great that no one could miss him. Isn’t this the point I made above…that everyone believes in God anyway? So it’s self-evident that God exists…right? Objection 1: Teaching of one of the Church Fathers Note the natural appeal of Damascene’s opinion, especially for a believer. We’re made in God’s image; of course the knowledge of him is implanted in us. Objection 2: St. Anselm’s famous «Ontological Argument» Logical legerdemain or metaphysical insight? The issue: God is so great that he cannot even be thought not to exist. Objection 3: Self evidence of truth If Jesus is the truth, then anyone who knows truth knows something of God, right? Sed Contra and Response: Self-evidence & the meanings of terms. Self evidence is a logical and conceptual notion, having to do with meanings of terms. “No bachelor has a mother-in-law” is self evident. Thomas Jefferson’s self-evident truths are not so for Aquinas. God’s existence is not and cannot be self-evident to us because we cannot know the divine essence. Digression on ‘essence’ and other Aristotelian concepts Essence: “what a thing is” When we know a thing’s essence, we have scientific knowledge of it. The essence is the basis of a thing’s definition. Also important are Matter: What that kind of thing is characteristically made of, and Form: What kind or class of being it is. Efficient cause: what made this thing to come into being. Final cause: the good at which the thing aims; its purpose or goal; its perfection. Potency and act Complementary opposites: Potency is potentiality, power or capacity to become something fully actual. Act is actuality, the realization of potentiality. Does God exist? Article three One of the most famous texts in philosophy and theology: St. Thomas Aquinas’s “Five Ways” to prove the existence of God. (For a very detailed version of the first argument, see Aquinas’s Summa Contra Gentiles, Volume 1. You can also check out Aristotle’s Physics, where these arguments first appeared.) Thomas’s strategy We cannot know God directly. All we can know are his works. If we look at his works (effects) we can know something about the maker that produced them. Therefore we can argue for God’s existence on the basis of things around us. The “Five Ways” 1. From motion: There must be an unmoved First Mover. 2. From efficient causes: There must be an uncaused First Cause. 3. From possibility & necessity: There must be a first Necessary Being. 4. From the gradation of things: There must be highest, best thing that causes all other goodness and perfection. 5. From governance of the world: There must be an intelligent being that directs everything to its goal. First Way – Change This argument (as well as the 2nd one) is drawn from Aristotle. Change is a fact of experience. But nothing changes without something else changing it. Nothing that has a potentiality makes that potentiality actual on its own. Everything that changes requires something that changes it. Whatever changes a thing must be changed by yet something else. This something else must also be changed. This cannot go on to an infinity of causes of change. Without some first cause, nothing else would change. Therefore there must be a First cause of change that is not itself changed. “This is what everyone understands by God.” Second Way This is perhaps the most common popular argument. “How did the universe get here?” There must be a God who made it. In the observable world, causes come in series. We cannot find anything that causes itself. But a series of causes can’t go on forever, for there would be no first cause and therefore no intermediate causes. o Eliminate a cause and you eliminate its effects. “So we are forced to postulate some first agent cause, to which everyone gives the name God.” Third Way To our modern ears a strange argument, the Third Way actually addresses important principles underlying the sciences and our understanding of the universe. Some things are possible to be or not to be, since they are generated and corrupted. They are made and destroyed. Were such ‘possible’ beings the only beings, then it would be impossible for the universe and what’s in it even to be. Beyond the ‘things’ in the universe are the necessary laws and principles by which things are governed. But the necessary laws and principles governing the universe must have an origin, a cause. They are not ‘just there’, unexplained regularities. Therefore there has to be a necessary Being from whom all other necessary beings receive their necessity. Fourth Way This is drawn from the Platonic tradition. Some things are more or less good, noble, beautiful, true, etc. than others. But “more” and “less” are said according to some absolute standard. (This is how Plato argued for his Forms.) So there must be something that is cause of the perfection in all other things and which is itself truest, noblest, best, and perfect in its being. “This is what we call God.” Fifth Way This argument is finding echoes today in the “intelligent design” school in biology. We see that inanimate objects act for a purpose. This is clear from the fact that they obey what we call natural laws. Hence, it is clear that their behavior is planned intelligently, just as an arrow is aimed by the archer. So, some intelligent being directs all things to their purpose, and this is God. “And this is what everyone calls God” This is the key to understanding these proofs. Everyone (almost) believes in a god of some sort. Whatever is to count as God—supreme over all other beings, all-powerful, all-wise, ultimate judge of good and evil—has to fit the criteria, as it were, in these proofs. What to make of these proofs Since they appeared, they have been subject of immense discussion and debate. In a way, they present a philosophical version of what ordinary people think, when they decide that there ‘has to be a God’ behind the world they live in. Their logical ‘bite’ Of course, you can refuse to accept them, but the price is to consign the universe to meaninglessness. There is no sense to anything and therefore no science and no ethical standard of good. Science does not affect their validity Modern and contemporary sciences neither refute nor support Aquinas’s Five Ways. These are not alternatives to physics. The Big Bang is not what Aquinas means by “first unmoved mover.” What they leave us with Clearly, the Entity whose existence is proved by Aquinas’s Five Ways does not look a lot like the God we worship in church. In fact, there is precious little that we can say positively about this being. We can, however, say a lot about what God is not. They do show—and for us in the 21st Century this is most especially important—that belief in God’s existence is not simply a matter of blind faith or subjective religious, moral, or aesthetic inclination.