Somatic-cell nuclear transfer or genetic cloning

advertisement

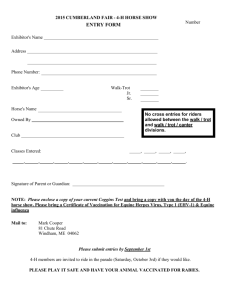

Is Cloning Here to Stay? By Deb Ottier Iron Horse Equine Printed Canadian Horse Journal Mar/Apr 2007 Introduction Somatic-cell nuclear transfer or genetic cloning seems like a sci-fi adventure, yet, there are several clones now on the ground from some of the horse industries top horses. The first cloning experiment involved a tadpole in 1952, with 1997 marking the birth of Dolly, the world renowned sheep clone. There is growing demand for this technology by the horse industry, but should we be dwelling on the past, or be preparing for the future? The Technique and its Success The actual technique, called somatic cell nuclear transfer, involves the microinjection of a DNA construct obtained from donor animals into an oocyte and transferred into recipients. Sounds like a mouthful, so put into simpler terms a piece of DNA from the donor animal is injected into an egg and transferred into carriers or hosts to carry the embryo to birth. This technology would produce a baby, not an adult that we see in some sci-fi movies. Figure 1 – Schematic representation of somatic cell nuclear transfer adapted from Vanderwall et al., 2004 This technology is expensive, inefficient and impractical at this time, but some are willing to pay the price to produce another “Big Ben”. The estimated cost to produce one clone is $150,000, with a second clone costing approximately $90,000. Looking at the success in clones currently in research news we have Dolly, the sheep that was the first clone, ever, well she was 1 out of 258 tries; the first mule that was cloned by the combined research teams from the Northwest Equine Reproduction Laboratory (University of Idaho) and Utah State University, was 1 out of 334 tries. In May of 2003, Researchers from the Laboratory of Reproductive Technology, a nonprofit research organization in Cremona, Italy, have produced a live foal cloned from skin cells from its own dam – which would mean the mare gave birth to herself. This was 1 out of 800 tries. What is Mitochondrial DNA? The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell responsible for supplying energy at the cellular level. Mitochondrial DNA is genetic information stored in the mitochondria. When the genetic information is removed from the egg during nuclear transfer, the mitochondrial DNA is left intact in the egg and hence, the final clone embryo. How does this impact the clones? This has not been eluded to in any of the research thus far, yet cloning utilizes eggs from a donor female. Could this potentially alter something in our clones? The Racing Mules The production of the first equid to be cloned, a mule, involved the nuclear transfer of DNA from a 45 day old mule fetus into an egg from a quarter horse mare. This first mule was born in May of 2003, with a second to follow that same year. While the technology is still relatively new, there are 2 mules that are now of racing age. Both mules raced against one another in June of 2006, and one would have expected there to be a dead heat, but that was not the case. Both mules were trained by different trainers with the outcome of the race being one mule coming in third, while the second clone came in seventh. Nature Vs. Nuture? While this technology would produce an identical individual genetically, we do have to consider that environment also has a strong influence of how the foal will develop. Such factors as nutrition, upbringing and training will influence if that individual will have the same performance rating. At a lecture by Dr. Ian Wilmut, the Scottish researcher responsible for the cloning of Dolly, he was put to the question of cloning a human, which is illegal, to obtain a child that had died in a tragic accident. He stated the environment would be very much different, so while you would have a genetically identical individual, you are older and have the experience of the first child and would do things differently in the upbringing of the child. Will this come into play in the horse world? Well, many European breeders will not utilize the technique of embryo transfer as they believe the mother plays a significant role in producing a champion based upon how she will raise the foal. It will be the all mighty dollar that will dictate the horses that are cloned, as with most technology. Geldings to Breed Ever wished you had not gelded that awesome performance gelding? Now the technology is available to produce the same gelding, only this time keep him intact. The primary obstacle will be in breed registry restrictions, as there will be genetically identical animals in the breeding books, which will make DNA marking very difficult. A gelding named “Gills Bay Boy” or Scamper won the hearts of many in years following 1985, as he and his rider, Charmayne James, rode into World Championship success for 8 consecutive years, making Scamper a world renowned barrel racer in his time. This quarter horse gelding obviously possesses superior genetics, but being a gelding, how could he pass on these remarkable qualities? Well, this gelding was cloned and has produced a colt which was introduced to the public as Clayton in November of 2006. This raises a couple of questions. Why was Scamper gelded in the first place? Would he have been the champion he was had he not been gelded? The colt is now coming up to breeding age, and the next step, how to handle the registration of foals from the clone. The American Quarter Horse Association rule 227 specifically states: “227. HORSES NOT ELIGIBLE FOR REGISTRATION (a)Horses produced by any cloning process are not eligible for registration. Cloning is defined as any method by which the genetic material of an unfertilized egg or an embryo is removed, replaced by genetic material taken from another organism, added to with genetic material from another organism, or otherwise modified by any means in order to produce a live foal.” So the big question, will this clone be able to provide its genetics to the gene pool of the Quarter Horse? That will be decided by the association and whether or not it intends to be a pro-active force in labeling cloned animals. Once they begin breeding, it will be very difficult to identify which came first, the chicken or the egg or in this case the clone or its 2nd clone… What the Future Holds With the current status on disease control, we are still seeing the emergence of new viruses and new problems, West Nile Virus, Avian Bird Flu, to name a few. By narrowing the gene pool with producing offspring that are genetically identical, how are we producing animals that will be able to resist these biological threats? Will the strong really survive? If breed registries take a pro-active role in the application of this technology by incorporating cloned animals in their registry, we will see more clones in the years to come. Although the equine industry is behind in applying the tremendous advances in reproduction already made in other species, the time will eventually come when a catalogue of banked genetic material will be available for breeders to choose their next crop of potential equine athletes. But is this the direction the horse industry should be taking or should the horse industry be trying to improve on the genetics we already have. References Ball BA. (2000) What Can we Expect for the Future in Stallion Reproduction? In: Recent Advances in Equine Reproduction, B. A. Ball, Ed. Ball BA. (2000) Reduced Reproductive Efficiency in the Aged Mare: Role of Early Embryonic Loss. In: Recent Advances in Equine Reproduction, B. A. Ball, Ed Vanderwall DK. (2000) Current Equine Embryo Transfer Techniques. In: Recent Advances in Equine Reproduction, Ball B.A. (Ed.) International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca NY, 2000 Vanderwall DK, Woods GL, Sellon DC, Tester DF, Schlafer DH, White KL. (2004) Present status of equine cloning and clinical characterization of embryonic, fetal, and neonatal development of three cloned mules. J Am Vet Med Assoc. Dec 1;225(11):1694-9. Woods GL, White KL, Vanderwall DK, Li GP, Aston KI, Bunch TD, Meerdo LN, Pate BJ. A mule cloned from fetal cells by nuclear transfer. Science. 2003 Aug 22;301(5636):1063. Epub 2003 May 29