KingAlfred

advertisement

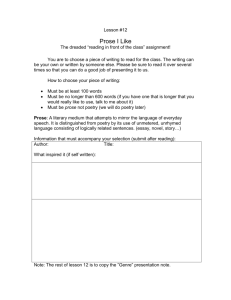

Poster presentation at the Statistical Society of Canada Conference Halifax, 7-12 June 2003 A Stylometric Analysis of King Alfred’s Literary Works Paramjit Gill Department of Mathematics & Statistics and Michael Treschow Department of English Okanagan University College, Kelowna, BC King Alfred the Great (848-899) Abstract For many centuries Alfred the Great was judged to have translated several Latin texts into Old English. Many scholars, however, have expressed doubt whether Alfred could have done all this work. With the availability of Old English Corpus in electronic form, it is feasible to subject the texts to statistical stylometric analysis. We use multivariate techniques for an exploratory analysis of use of “function” words in various Alfredian and non-Alfredian texts. We find that three translations (Pastoral Care, The Consolation of Philosophy and The Soliloquies) that have been attributed to Alfred, indeed cluster together on the frequency of usage of function words. However, one translation still attributed to him, The First Fifty Prose Psalms, tends to stay away from the Alfredian texts. Introduction After King Alfred the Great defeated the Vikings at the battle of Edington in 878 he turned to strengthening his English kingdom of Wessex that had suffered so greatly under the Viking invasions. Most famous is his program for educational reform. Alfred depicts himself as a philosopher-king, taking up scholarship in his own right and making English translations of Latin patristic texts to serve as the basis of education in the English language. Seven translations are associated with his reign. The following three internally identify themselves as Alfred’s work: 1. Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care 2. Boethius's The Consolation of Philosophy 3. Augustine's The Soliloquies The other four translations are: 4. Gregory the Great's Dialogues 5. Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People 6. Orosius's Histories against the Pagans 7. The First Fifty Prose Psalms Of these four only Gregory’s Dialogues clearly identifies itself as not Alfred's work. Alfred himself wrote its preface explaining that he directed his friends to make it. The other three do not identify any translator, but tradition long held that they were the work of King Alfred. William of Malmesbury, a twelfth century historian, listed Bede's History and Orosius's History among Alfred's translations and also stated that Alfred was working on a translation of the Psalms at the time of his death. Old English scholars, however, have come to accept that Alfred could not have translated Bede's History because, like the translation of the Dialogues, it shows traces of the Mercian dialect. Alfred's authorship of the Orosius has also recently been overthrown. Bately (1982) however, has argued that the translation of the First Fifty Prose Psalms is Alfred's. Bately assessed the authorship of the Orosius and the Prose Psalms by analysing how they translated certain Latin words. She noted that the Prose Psalms usually used the same Old English words to translate corresponding Latin words as did the three Alfredian texts, but that the Orosius showed greater differentiation. Stylometry allows for a much more refined and extensive analysis, not only of contextual words but also, and more importantly, of non-contextual words. The question now arises whether a more thorough stylometric analysis would confirm Bately's conclusions. As we are dealing with Old English translations from the original Latin, we face a special challenge that does not arise in standard stylometric analysis where the problem is the authorship assignment of original work. It is important to note, however, that the work of translation is itself a kind of authorship that can be subjected to stylistic analysis. The translations considered in this study all stand at the beginning of Old English prose writing. They show the initial development of English prose style. The proem to the translation of Boethius states that Alfred's strategy of translation was variable, sometimes rendering "word for word, sometimes sense for sense." All these translations exhibit an authorial voice that forms the text into the Old English language. Data The raw data for this study were generated through the Dictionary of Old English Corpus available in CD format from the University of Toronto. We copied the seven documents in ordinary text along with various tags (line numbers etc.). We divided the texts into blocks of about 50 lines, each accounting for about 1200 words on average. These blocks are the unit of statistical analysis. Table 1. Sizes of the Texts Total Size (words) 77,500 Number of Blocks 58 Mean Block Size (words) 1340 BO: Boethius 46,200 39 1180 CP: Pastoral Care 67,650 51 1330 GD: Gregory’s Dialogues 91,000 63 1450 OR: Orosius 48,900 40 1220 SO: Soliloquies 15,400 16 960 PP: Prose Psalms 19,400 17 1140 Text BE: Bede Function Words An underlying principle of statistical stylometric analysis is that writers use some common highfrequency words unreflectively in their writing. These words are called function words, and occur regardless of context. They can be prepositions, conjunctions, articles, and common verbs. Different authors, however, use them at different rates. Therefore, stylometric analysis can exploit differential rates of function words to distinguish authorship. For analysing the seven texts, we generated a list of the 100 most frequent words common to all seven texts. We refined the list by omitting all contextual words. We further omitted all words that might depend on the original Latin text and chose those words that were distinctively English and expressive of English style. Table 2 shows the list of the 17 individual function words (with the modern English meaning in parentheses) that we used for stylometric analysis. Multiple spellings for many of these words were accounted for and combined, as in the case of ÞEAH, ÐEAH, ÞÆAH, ÐÆAH, ÞEH, ÐEH. Table 2. Function Words _____________________________________________________________________________________ AC (but) AND (and) BIÐ (is) EAC (also) HIT (it) IS (is) MIÐ (with) OF (of) SWA (so) TO (to) ÐA (those, then) ÐÆS (of the) ÐÆT (that) WÆS (was) WIÐ (against) ÐONNE (then) ÐEAH (although) We used WordSmith Tools (Scott, 1998) to count the frequency at which these function words occur in text blocks. The count was then converted to frequency per 100 words in the block. Our dataset then consists of 284 rows of text blocks and 17 columns of function words. As we see in Table 3, there is a wide variation in the frequencies of the words over the seven texts. Table 3. Mean Frequency of Function Words in 7 Texts BE BO CP GD OR SO PP AC 0.30 0.85 0.70 0.54 0.40 0.79 0.50 AND 6.50 3.97 3.80 5.01 5.91 3.89 7.03 BIÐ 0.10 0.74 0.77 0.22 0.06 0.25 0.44 EAC 0.51 0.35 0.48 0.58 0.33 0.42 0.40 HIT 0.17 1.06 0.87 0.72 0.52 0.96 0.24 IS 0.52 1.07 0.81 0.45 0.38 0.77 0.83 MIÐ 1.40 0.63 1.17 1.13 1.19 0.44 0.76 OF 0.48 0.21 0.24 0.54 0.41 0.20 0.41 SWA 0.94 1.45 1.31 1.30 0.86 1.77 1.16 TO 1.68 1.10 1.91 1.54 1.37 1.11 1.55 ÐA 3.68 2.76 2.75 4.13 3.11 2.62 1.73 ÐÆS 0.97 0.67 0.73 1.16 0.57 0.56 0.29 ÐÆT 2.48 4.23 3.82 3.61 3.17 4.45 1.96 ÐEAH 0.09 0.72 0.50 0.18 0.29 0.64 0.36 ÐONNE 0.27 1.44 2.02 0.41 0.49 1.15 0.62 WÆS 2.17 0.26 0.38 1.49 1.59 0.18 0.25 WIÐ 0.10 0.22 0.19 0.05 0.53 0.05 0.34 Principal Component Analysis The first five principal components (PC’s) explain about 82% of the variability and the most prominent function words in these PC’s are the 10 words: AND, HIT, IS, MIÐ, SWA, TO, ÐA, ÐÆT, WÆS, ÐONNE. More importantly, the first two PC’s clearly show the separation of Alfred’s work from Bede, Gregory’s Dialogues and Orosius (Fig 2). The most interesting revelation from Figure 2 is that Prose Psalms stay away from Alfredian texts. This casts a doubt on Bately’s conclusion that Prose Psalms are Alfred’s translation. Of course, we need more detailed confirmatory statistical analysis to investigate it further. Fig 1. Factor Loadings for the Most Prominent Words -0.2 0.4 -0.6 0. 0.6 -0.2 0.4 -0.4 0.2 0.8 -0.6 0. Comp . 1 AN p D AWA ET p E ON S p AH NE I T Comp . 2 p AA N WA D p E A S p E ON TI S NE Comp . 3 pA E AT N T D O p ON H N I T MI E D Comp . WA p E A S I S 4 AN p D ON MI N D E Comp . 5 TO p ON S WA N p E AE MI T D A ND Fig 2. First two Principal Components Bede 3 Alfred Second Principle Component 2 GD OR 1 PP 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 First Principle Component 2 3 4 Cluster Analysis To get an idea about the closeness of usage of function words in various texts, we ran a cluster analysis on data on 17 function words. When asked to produce three clusters, the 284 text blocks were divided as shown in Table 4. We see that most of the text blocks from Boethius, Pastoral Care and Soliloquies cluster together (cluster 3) and majority of Bede, Gregory’s Dialogues and Orosius blocks go to cluster 2. Cluster analysis confirms our suspicion about the Prose Psalms with all the 17 text blocks staying in a cluster of their own (cluster 1). However, about one-third of each of Bede and Orosius blocks also go along with Prose Psalms. Table 4. Cluster Membership using K-Means Clustering Text Number of blocks in Cluster 1 Cluster 2 Cluster 3 Bede 13 43 2 Boethius 1 1 37 Pastoral Care 1 2 48 Soliloquies 2 0 14 Gregory’s Dialogues 2 57 5 Orosius 11 29 0 Prose Psalms 17 0 0 0OR 50 BO 10 150 OOR OR ROROR OSR OR OR OSOR OR CP BO SOP OR OR CP PP PP P CP BO BO SO CP CP BOBOBO CPCP CPCP CPCP CPCPCP CP CP BOBO CP BO BO SO CP CP BOBO SSOO BOBO BO SO Fig 3. Cluster Analysis of Boethius, Pastoral Care, Soliloquies, Orosius, and Prose Psalms using 17 Function Words Figure 3 shows hierarchical clustering where we used text blocks only from Boethius, Pastoral Care, Soliloquies, Orosius and Prose Psalms. Here also, we see that Prose Psalms don’t cluster along with Alfredian texts and rather tend to stay close to Orosius. Bibliography Bately, J. (1982) Lexical evidence for the authorship of the prose psalms in the Paris Psalter. AngloSaxon England, 10, 69-95. Scott, M. (1998) WordSmith Tools Manual, version 3.0, Oxford University Press. Acknowledgements This research is being supported by a grant in aid of research at OUC and a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada.