London Clubs and Victorian Politics

advertisement

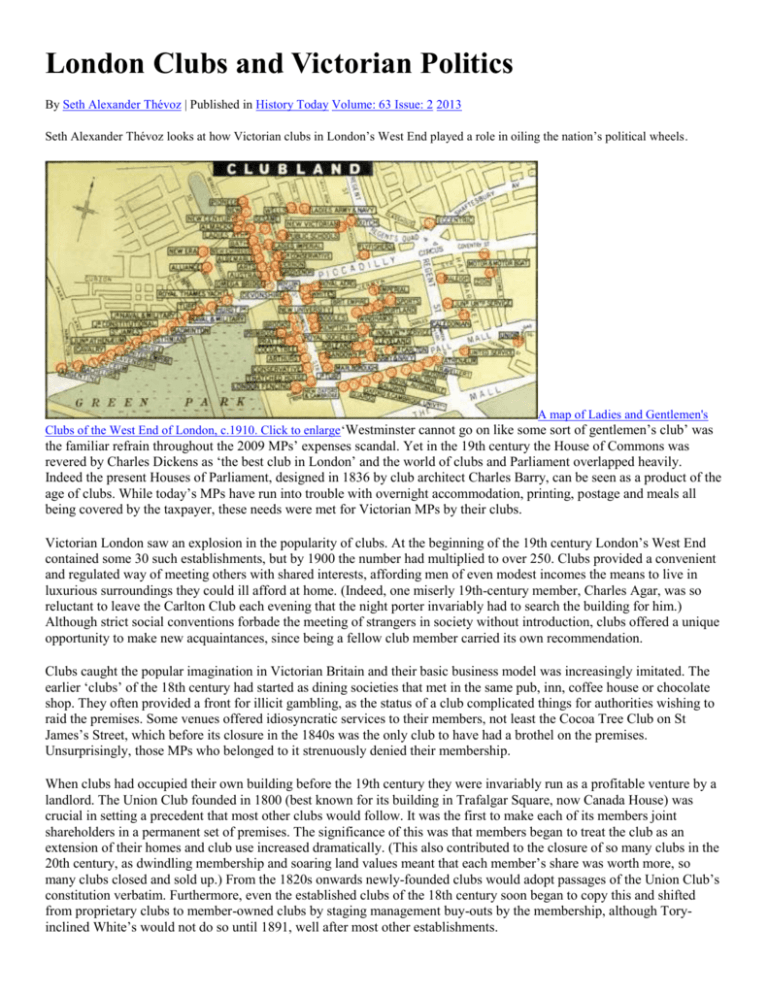

London Clubs and Victorian Politics By Seth Alexander Thévoz | Published in History Today Volume: 63 Issue: 2 2013 Seth Alexander Thévoz looks at how Victorian clubs in London’s West End played a role in oiling the nation’s political wheels. A map of Ladies and Gentlemen's Clubs of the West End of London, c.1910. Click to enlarge‘Westminster cannot go on like some sort of gentlemen’s club’ was the familiar refrain throughout the 2009 MPs’ expenses scandal. Yet in the 19th century the House of Commons was revered by Charles Dickens as ‘the best club in London’ and the world of clubs and Parliament overlapped heavily. Indeed the present Houses of Parliament, designed in 1836 by club architect Charles Barry, can be seen as a product of the age of clubs. While today’s MPs have run into trouble with overnight accommodation, printing, postage and meals all being covered by the taxpayer, these needs were met for Victorian MPs by their clubs. Victorian London saw an explosion in the popularity of clubs. At the beginning of the 19th century London’s West End contained some 30 such establishments, but by 1900 the number had multiplied to over 250. Clubs provided a convenient and regulated way of meeting others with shared interests, affording men of even modest incomes the means to live in luxurious surroundings they could ill afford at home. (Indeed, one miserly 19th-century member, Charles Agar, was so reluctant to leave the Carlton Club each evening that the night porter invariably had to search the building for him.) Although strict social conventions forbade the meeting of strangers in society without introduction, clubs offered a unique opportunity to make new acquaintances, since being a fellow club member carried its own recommendation. Clubs caught the popular imagination in Victorian Britain and their basic business model was increasingly imitated. The earlier ‘clubs’ of the 18th century had started as dining societies that met in the same pub, inn, coffee house or chocolate shop. They often provided a front for illicit gambling, as the status of a club complicated things for authorities wishing to raid the premises. Some venues offered idiosyncratic services to their members, not least the Cocoa Tree Club on St James’s Street, which before its closure in the 1840s was the only club to have had a brothel on the premises. Unsurprisingly, those MPs who belonged to it strenuously denied their membership. When clubs had occupied their own building before the 19th century they were invariably run as a profitable venture by a landlord. The Union Club founded in 1800 (best known for its building in Trafalgar Square, now Canada House) was crucial in setting a precedent that most other clubs would follow. It was the first to make each of its members joint shareholders in a permanent set of premises. The significance of this was that members began to treat the club as an extension of their homes and club use increased dramatically. (This also contributed to the closure of so many clubs in the 20th century, as dwindling membership and soaring land values meant that each member’s share was worth more, so many clubs closed and sold up.) From the 1820s onwards newly-founded clubs would adopt passages of the Union Club’s constitution verbatim. Furthermore, even the established clubs of the 18th century soon began to copy this and shifted from proprietary clubs to member-owned clubs by staging management buy-outs by the membership, although Toryinclined White’s would not do so until 1891, well after most other establishments. The effect was dramatic and signalled a marked increase in club use. Other institutions began to operate along the club model, such as the London Library in 1841, which grew out of the Travellers’ Club library and granted access to its private reading rooms in exchange for a subscription. The middle of the century saw new clubs extend from the aristocracy to the professional and middle classes, as an increasing number were themed around professions and interests: the military, the civil service, expatriate nationalities and the arts and sciences. Far from their fusty image today, the new wave of 19th-century clubs used the latest technologies available: gas lighting, electricity and telegraph wire newsfeeds. Contrary to popular belief, they were not an exclusively male preserve. Femaleonly clubs such as the Ladies’ Athenaeum and mixed clubs like the Albemarle also flourished. Male clubs tended to predominate among those that survived from that era, so we are left with an unrepresentative idea of Victorian clubland. However it was nowhere near as exclusive as its reputation suggests. From the 1850s onwards, the Reverend Henry Solly (1813-1903) founded a nationwide network of thousands of working men’s clubs that sought to bring a slice of Pall Mall to the masses and by 1900 any middle-class man could find at least one club willing to admit him. But it was for their political rather than their social clout that the London clubs had the greatest impact. The 1832 Reform Act created several hundred thousand new electors, people who consciously defined themselves as middle class. Shunned by the traditional political and aristocratic citadels of Brooks’s and White’s, this group founded their own more ‘popular’ political establishments, led by the Conservative-supporting Carlton Club in 1832 and the Liberal-supporting Reform Club in 1836. The Great Fire of 1834 destroyed the old Palace of Westminster and, although the new House of Commons chamber was completed by 1852, Parliament remained a noisy building site well into the 1860s. For the whipping and lobbying activities that are an essential part of any parliamentary democracy, MPs had nowhere to go except to their clubs. These afforded MPs cheap and convenient all-night dining in central London, in several cases with the doors timed to close an hour after Parliament ceased sitting. While the political influence of elite clubs proved transient, they nonetheless played a critical role in the evolution of parties and politics. In the 1830s the Liberal whip Edward Ellice popularised the phrase ‘Club Government’, as the Carlton and Reform Clubs housed national offices for the Conservative and Liberal parties (complete with printing presses and facilities for franking mail), pre-dating the creation of central political organisations in the 1870s. Hansom cabs ferried MPs from Pall Mall to Parliament in an eight-minute round trip, as the clubs became a convenient place for whips to pick up scores of MPs before a vote. Most clubs had strict caps on membership numbers, but in political clubs MPs were exempt from such limits, so could join in large enough numbers to exercise significant influence. The clubs were a means of controlling the scourge of lobbying interests by limiting the number of interlopers. MPs were further attracted by the security of conventions such as the expectation that conversations held within their walls would not be divulged outside them. Of course this naturally fuelled gossip as to what went on behind closed doors. Indeed in 1844 The Times dared to print an account of a meeting by rebellious Conservative MPs at the Carlton, which prompted furious letters, as Disraeli was widely suspected of being the ‘leak’. As with modern parliamentary expenses, the perks offered by clubs could be abused by MPs. In the 1840s the unscrupulous Peter Borthwick used the Carlton Club’s cloak of respectability to run fraudulent businesses from its address. A blind eye was often turned to such things by the management. When a female creditor pursued Borthwick to his business address in 1842 the club’s committee expressed dismay at the presence of a woman on the premises, yet remained silent about his business affairs. Clubs tell us much about Victorian values. Just as the franchise was extended to the groups that it was believed represented all that was best in Britain, so London clubs sought to capture the best that the metropolis had to offer. In its 19th century heyday the club not only stood as an innovative way of brokering social interactions, it also allowed MPs to meet the costs of sitting in Parliament without burdening the taxpayer. Seth Alexander Thévoz is completing a PhD on 'The political impact of London clubs, 1832-68' with the History of Parliament Trust and Warwick University, where he is a seminar tutor.