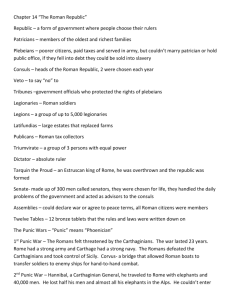

The History of Rome by Michael Grant

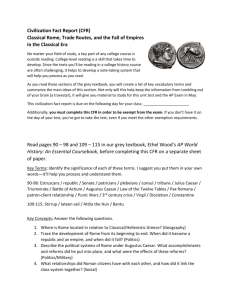

advertisement