Eddie Geoghegan Irish Coats of Arms & Heraldry web pages http

advertisement

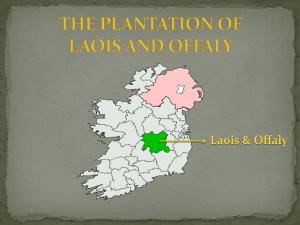

Eddie Geoghegan Irish Coats of Arms & Heraldry web pages http://homepage.tinet.ie/~donnaweb/ Ireland was one of the earliest countries to evolve a system of hereditary surnames. They came into being fairly generally in the eleventh century, though some were formed as early as the year 1000. Brian Boru, high king of Ireland, who died at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, is often erroneously credited with decreeing that the use of surnames should become a requirement among his subjects. In fact the system developed spontaneously in Ireland, as it did elsewhere, as a result of the need for personal identification in an increasing population. Prior to the adoption of surnames, the Irish had a system of tribal grouping that went under formal names. These included, among others, Cenel Conaill, located in the north-east and traditionally descended from Conall Gulban, son of Niall of the Nine Hostages. Cenel Eoghain, located in Tyrone and Derry and traditionally descended from Eoghan, son of Niall of the Nine Hostages. Cenel Fhiachadh, located in the midlands and descended from Fiacha, third son of Niall of the Nine Hostages. Dal gCais or Dalcassians, descendants of Cas and located in Thomond - counties Clare and parts of Limerick and Tipperary. Eoghanacht, centered in south Munster and descended from Eoghan, son of Oilioll Olum, King of Munster. Siol Muireadhaigh or Silmurray, located in north Connacht. Uí Fiachrach, two groups, Uí Fiachrach Muaidhe, located in north Mayo and Sligo and Uí Fiachrach Aidhne in south Galway. Uí Maine or Hy Many, located in east Galway and South Roscommon. These groups were often parts of others and also subdivided so the situation is not as simple as it might seem. For example, Uí Neill or Ua Neill was a collective name for all the descendants of Niall of the Nine Hostages. It included the northern Uí Neill (which in turn included Cenel Conaill and Cenel Eoghain) and the southern Uí Neill (which in turn included Cenel Fiacha and others). The existence of these named groups indicates a predisposition among the ancient Irish towards family grouping and naming and so it is not surprising that the development of personal and hereditary surnames was little more than a natural extension of this tribal system. Prior to the coming of surnames, individuals were identified by means of a personal name, sometimes with the addition of a nickname referring to some deed or physical attribute, for example Con Cead Cathach (Con of the hundred battles), Feargal Ruadh (red haired Fergal), Roisin Dubh (dark haired Rose) and so on. The people of the time must have also used patronymics, Eoin Mac Brian (John son of Brian), etc., but names were not hereditary, for instance, Eamonn, the son of Eoin Mac Brian, would be known as Eamonn Mac Eoin (son of John) rather than Eamonn Mac Brian (Brian). However, as surnames gradually became hereditary, these patronymics remained constant from one generation to the next. Patronymics form the great majority of Gaelic-Irish surnames. They are formed by adding the prefix "Mac" or "O" to the personal name of an ancestor. "Mac" literally means "son" and "O" means grandson, but in surnames, both are usually taken to signify "descendant of" rather than their literal meaning. The great Irish patronymics give us quite an insight into the popular personal names of the day, Neill, Connor, Murchadh (hence Murphy), Aodh or Hugh (hence McKay, McHugh, O Hea, etc.), Conall, etc. I should mention that the use of the form Mac, Mc, M', Mag, etc. is of no significance. All are simply variants of the Gaelic word "mac". I should also mention that these prefixes are gender sensitive, Mac and O being masculine. Their feminine equivalents are Ní (Nic if followed by a vowel) and Uí. Apart from patronymics, the other three great sources of all surnames, not just in Ireland, are, occupational, nicknames and locative. Surnames based on nicknames abound among the Irish. O Sullivan is from "suil amhain" meaning one-eyed, Deeny is from "duibhne" meaning disagreeable, Roe from "ruadh" meaning red haired, Duff, Duffy, Deegan and several other surnames are all derived from the root word "dubh" (pronounced duvv or duw) meaning black. Occupational names are somewhat less common. Clery is "O Cleirigh" from the Irish word for clerk and McGowan (Mac Gabhan) is from the word for smith. Locative surnames (derived from the bearer's place of birth or where they lived), are far less common among the Irish than the English or Normans. However, there are some examples for instance De Gallbhaille (Galbally). There are two other types of Irish surname that I should mention, both derived by the addition of a prefix. In the first case the prefix is "Giolla" which means "follower of", "devotee of" or "servant of". This prefix has given rise to a large number of familiar names start with Gil... or Kil... For example, Gilmore is from Mac Giolla Mhuire (devotee of Mary), Kilbride from Mac Giolla Brighde (devotee of St. Bridget, Gildea or Kildea from Mac Giolla Dhe (servant of God), Gilleran from Mac Giolla Eanain (Eanain's servant). The second case relates to the prefix "maol" which can have the same meaning as "Giolla", i.e. devotee, etc. but which may also be derived from "mal" meaning leader or chief. From this prefix we get a whole series of names beginning Mul... Mulcahy from O Maolcathach (leader of battles), Mulderrig from O Maoildeirg (red chief), Mulhall from O Maolchathail (follower of Cathal), Mulholland from O Maolchalann (devotee of Saint Calann), and many more. And so it was that by the end of the twelfth century, names derived as explained above existed all over Ireland. However, a major event was about to happen. In 1170, the Anglo-Normans arrived in Ireland and over the course of a hundred years mingled and intermarried with the native Irish. With them came a whole new selection of names and conventions. The Anglo-Normans were mainly French speaking. Many of them were grandchildren or great-grandchildren of those who made up the force, which under William the Conqueror, subjugated the native English in 1066. Some of them had already taken surnames based on their exploits in England. For example, the leader of the invading force, Richard de Clare, better known as Strongbow, had already derived his name from a place in England. Other family, the D'Exeters derived their name from that town. However, over time, a large number of these families adopted Irish ways and Irish names. For example, the descendants of one Jordan D'Exeter adopted the patronymic Mac Suirtain, later to become anglicised as Jordan. The great family of Burke (de Burgo, de Burgh, de Burca) split into several sub-septs with names like MacHugo, MacGibbon, MacSeoinin (Jennings), MacRedmond, Mac Uilic (MacGillick) and more. The Normans also gave birth to the famous Fitz... names, the prefix being derived from the French "fils" meaning son. The Fitzgeralds, Fitzsimons, Fitzgibbons, Fitzhenrys and so on, all adopted Irish customs and became "more Irish than the Irish themselves". It is worth mentioning that not all Fitz... names are Irish. Among the Normans of England a similar practice arose and the Fitzalans, Fitzcharles's, Fitzgeffreys, etc. of that country are as blue blooded as any English family, many having no connection whatsoever with Ireland. I should also quickly mention the Fitzpatricks who are the exception to the rule. This family is Gaelic-Irish, being Mac Giolla Phadraigh (devotee of Saint Patrick). The name was first anglicised Gilpatrick, but, perhaps in an attempt to make a fashion statement, the main family adopted the Fitzpatrick form, though they have no French connection. Gallowglasses were mercenary soldiers, imported by the Irish clan chiefs, both Gaelic and Norman, mainly in Ulster but also further afield, to aid in the defence of their clan territories. The first recorded arrival of Galloglasses was in 1259. Prince Aedh O Connor of Connaught, son of King Feidhlim married a princess, daughter of Dubhgall MacRory King of the Hebrides. As part of her dowry she brought with her a force of 160 Galloglasses. They came for the most part from Inse Ghall (The Hebrides) and were Gaelic speaking Scots interbred with Vikings. Because of their Viking blood they earned the name from the words gall (foreign) and óglaigh (a warrior). The Scots themselves were Irish, mainly the Dal Riada from Northern Ireland who had traveled to Western Scotland and Hebrides. A fifteenth century account of them states: "They, the Irish, have one sort of footmen which can be harnessed in mail and basinettes, having every man of them a kind of battle-axe and they be named gallowglasses. These sort of men be those that do not lightly abandon the field, but bear the brunt to the death. These men are commonly wayward by profession than by nature, big of limb, burly of body, well and strongly timbered, chiefly feeding on beef, pork and butter." They earned their reputation the hard way, and were one of the reasons the chieftains of Ulster and Connaught slowed the English advance northward from the Pale several hundred years. Many of them got grants of land from the Irish chiefs and went on to found some of the most respected septs of the island. The best known of therese are MacSuibhne (MacSweeney), MacDomhnaill (MacDonnell), MacSíothaigh (MacSheehy), MacDubhgaill (MacDougall), MacCaba (MacCabe) and MacRuari (MacRory). Lesser known Galloglass families include MacSorley, MacNeill, MacGreal, MacAnGhearr (Short / Shortt / McGirr), MacAnGallóglaigh (MacGallogly / English), MacClean(MacAlean / MacLean / MacClane), MacAilín (MacCawell / Campbell / MacCampbell / Allen / MacEllin), MacAlister (MacEllistrum / MacAllister / MacAlistrum), MacAlexander, Agnew (O Gnimh / O Gnimha / O Gnive) and MacPháidín (MacFadden). The native Irish and the now naturalised Normans led a normal, if not totally peaceful co-existence for several hundred years, during which time many new surnames came into existence as the fortunes of families and septs waxed and waned. Up until the sixteenth century, many emigrant families settled in Ireland from England, Wales, Scotland and the continent. Many of these came to escape persecution in their native lands and they added to the growing list of "Irish" surnames. When Henry VIII broke with Rome, many catholic English fled to Ireland despite the fact that Henry had declared himself King of Ireland. On a side note, it is worthy of mention that Henry VIII declared that the coat of arms of Ireland should be "Azure a Harp Or" (a gold harp on a blue background) thus changing it from the famous three crowns motif (as on the current arms of Munster), which he felt might be construed as representing the triple tiara of the Pope. Henry, is known to have considered a plantation of Ireland with loyal subjects as a method of subduing the native Gaels and the rebellious Anglo-Normans. However, he gave up on the idea for reasons of finance. When Queen Mary, a Roman Catholic, came to the throne in 1553, she repealed the anti-Rome laws and made England Catholic again. This was welcomed by the Irish, but Mary did not seem to regard her common religion as any reason to treat Ireland any more kindly than her Protestant predecessor. She sent her army into what is today counties Laois and Offaly in 1556 and forcibly removed most of the native Irish from the area and gave it to English (and mainly Catholic) settlers. The counties were renamed as Queen's County and King's County. For 50 years, the Irish who had been removed relentlessly attacked the settlers and it wasn't until 1600 that the attacks faded away. By then, many new English surnames were well established in the area. In 1558 Elizabeth I came to the English throne and made England Protestant again. Although she was funding colonies in the vast, newly discovered, land to the west across the Atlantic she still regarded Ireland as a much more convenient place to colonise, being so much closer and of similar climate to England. Her reign was dogged by rebellions in Ireland. An attack by the O Neills of Tyrone was defeated in 1561 and two revolts by the FitzGeralds of Cork and Kerry were put down in 1575 and 1580 respectively. Elizabeth took advantage of the defeat of the FitzGeralds in Cork and began a plantation in Munster. Promising people the same kind of wealth that people were finding in the Americas, many English came and settled in what had been FitzGerald land. The land was quickly farmed, towns developed and the colony was prospering by 1587. However, the colony was devastated in 1598 by a co-ordinated Irish attack from which it never recovered, although many English remained in isolated areas. By 1598, Ulster was the last bastion of pure Celtic life in Ireland. The genetics and culture of most of the rest of Ireland had mingled with Viking, Norman and then English settlers and was a now hybrid containing cultural components of Celtic, Viking, Norman and English origins. Ulster was largely shielded from these changed because it was defended by strong clans, particularly the O Neills in Tir Eoghain. It wasn't until 24 December 1601 at the battle of Kinsale that O Neill's army was defeated. The English decided to plant Ulster with Protestant settlers. However, the lesson of previous plantations had been learned. In the Laois / Offaly plantations and particularly in Munster, the settlers had been badly affected by attacking Irish. So this time the settlers were to live in specially built fortified towns known as Plantation Towns. In 1609 the English mapped out 4,000,000 acres of land and started gaving it out in 1610. Counties Down, Monaghan and Antrim were planted privately. Counties Derry and Armagh were planted with English. Counties Tyrone and Donegal were planted with Scots. Counties Fermanagh and Cavan were planted with both Scots and English. The vast majority of the settlers were Scottish, as it turned out, and they brought with them a new form of Christianity, Presbyterianism, which was different from both Roman Catholicism and the Church of England, although it is classified as Protestant. They also brought new farming methods and a Puritan lifestyle. This made north-east Ireland culturally very different from the rest of the island. Many native Ulstermen attacked the settlers and burned crops. Some were shipped to the continent. However many native Irish stayed and became employees of the settlers, and the Ulster Plantation became the most successful plantation to date. The plantation brought a whole influx of new surnames into Ireland. The new surnames of English origin were, at first, easily spotted, with Smiths, Taylors, Fleetwoods, etc. standing out from the established names. Some of the Scottish names had an Irish look to them, but the Johnstons, Armstrongs, Elliots, Irvines, Nixons, Croziers, and so on were easily spotted. The Norman-Irish lords -- now called "Old English" to distinguish them from "New English" settlers and the "Gaelic Irish" - were largely unaffected by the Ulster Plantation. However, after the execution of Charles I, Oliver Cromwell brought his army to Ireland and quashed a rebellion with a savagery that has become legendary. Cromwell and his Puritans spelled disaster for all Catholics, but particularly for the Norman-Irish. Puritans were virulently anti-Catholic, and England's traditional tolerance for the "Old English" (vis-a-vis "Gaelic Irish") quickly became extinct, with both communities now treated as Catholic enemies of England. The Cromwellian Plantation followed the war. It was the largest and most acrimonious of the confiscations, reducing Catholic ownership of land another 37%, from 59% to 22% Whereas the Ulster Plantation had confiscated land principally from the Gaelic-Irish, the Cromwellian Plantation took land largely from "Old English" Catholics, and transferred it to Cromwell's soldiers (in lieu of back pay) and to investors in the war effort. By the mid 1660s, the Cromwellian and Ulster Plantations had created a huge landlord class, including the oft-vilified absentee landlords, whose rental income often permitted them to lead lives of leisure, while backbreaking rents had thrust the native Irish into abject poverty, with 85% of the populace living at subsistence level. After the restoration of the monarchy in England, the old line Irish (the descendants of the pre-17th Century Irish, including both Gaelic-Irish and Norman-Irish Catholics) arose again when they took sides in a war between two claimants to the English Crown. They supported James II, against the man who had deposed him, William of Orange. At the Battle of the Boyne (July 1, 1690), William's army handily defeated James' forces. James immediately fled back to France, but the Irish (with some French support) continued the fight for more than a year before suffering a devastating defeat at Aughrim. Finally, Sarsfield negotiated an honorable surrender embodied in the Treaty of Limerick (1691) as a result of which Sarsfield and more than 10,000 Irish troops left Ireland for the Continent - the celebrated "flight of the 'Wild Geese - and became legendary soldiers in the armies of France and other continental powers. There ensued the third and final wave of 17th Century plantations (the "Williamite Plantation"), which reduced Catholic ownership of land from 22% to 14%. In 1603, before the Battle of Kinsale, about 95% of land in Ireland was owned by Catholics (the Gaelic Irish, the Norman Irish and the Old English); by 1701, less than a century later, only 14% was owned by Catholics, an aggregate transfer of 81% of all productive land in Ireland. Further, the percentage of non-Irish in the population had been increased from 5% to 25%. Further suppression of all things Irish, resulted in an insistence that all Irish names be given an anglicised form. This resulted in a general dropping of the "Mac" and "O" prefix and to a lesser, but still significant, extent "Mul", "Gil" and "Kil" started to disappear. In a country where the majority of the population spoke Irish rather than English, it was inevitable that English-speaking civil servants would create an amazing array of anglicised forms of the old Irish names. Some were anglicised phonetically and others by translation (or more often than not, mis-translation). So MacGabhain became both (Mc)Gowan (phonetic) and Smith (translation), Mac an Tuile became Tully (phonetic) and Flood (mis-translation). The last century has seen a resurgence in the use of Gaelic names in Ireland and abroad. This has resulted in a widespread readopting of Mac and O prefixes. However, this has not always been quite consistent with the original names. There are many examples of names that were original of the "Mac" type, being reborn with an "O" prefix. For example, Gorman was originally MacGorman, but when found with a prefix in Ireland today, it is usually (incorrectly) O Gorman. One absurd example is the case of the English name Odell (originally Odehull) being made O Dell. In summary, the majority of surnames found in Ireland today can be traced to one of four major sources. These are, native Irish, Norman, English planters and Scottish planters. There are of course others such as surnames from Wales and continental Europe. The locations of the ancient territories, which may be mentioned in the family histories, can be equated with modern counties as follows o o o o o o o o o o o o o o Breffny (Breifne): Counties Cavan and West Leitrim Corca Laoidhe: Soutwest Cork Dalriada: North Antrim Decies (Deise): West Waterford Desmond (Deasmhumhan): Kerry and much of Cork Iar Connacht: West Connaught, mainly Connemara Meath (Kingdom of): Counties Meath and Westmeath with parts of Offaly, Kildare, Wicklow, Dublin and Louth. Muskerry (Muscraidhe): Northwest and Central Cork Oriel (Orghialla): Armagh and Monaghan with parts of South Down, Louth and Fermanagh Ormond (Urmhumhan): Much of counties Kilkenny and Tipperary Ossory: County Kilkenny and adjoining parts of bordering counties Thomond (Tuathmhumhan): Most of Clare with adjacent parts of Limerick and Tipperary Tirconnell (Tir Chonaill): Donegal Tirowen (Tir Eoghain): Tyrone with adjacent parts of Derry. Based on Matheson's Census of 1890, the one hundred most common surnames in Ireland, with their origins, at that time were 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. (O)Murphy (Gaelic Irish) (O)Kelly (Gaelic Irish) (O)Sullivan (Gaelic Irish) Walsh (Norman) Smith (Gaelic Irish from Mc- and O Gowan and also English) (O)Brien (Gaelic Irish) (O)Byrne (Gaelic Irish) (O Mul)Ryan (Gaelic Irish) 9. (O)Connor (Gaelic Irish) 10. (O)Neill (Gaelic Irish) 11. (O)Reilly (Gaelic Irish) 12. Doyle (usually Norse also a form of McDowell which is Scottish gallowglass) 13. (Mc)Carthy (Gaelic Irish) 14. (O)Gallagher (Gaelic Irish) 15. (O)Doherty (Gaelic Irish) 16. (O)Kennedy (Gaelic Irish) 17. Lynch (Norman and Gaelic Irish) 18. (O and Mc)Murray (Scottish and Gaelic Irish) 19. (O)Quinn (Gaelic Irish) 20. Moore (Gaelic Irish from O More and also English) 21. (Mc)Loughlin (Gaelic Irish also substituted for the Gaelic name O 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. Melaghlin) (O)Carroll (Gaelic Irish) (O)Connolly (Gaelic Irish) (O)Daly (Gaelic Irish) (O)Connell (Gaelic Irish) Wilson (English and Scottish (O)Dunne (Gaelic Irish) (O and Mc)Brennan (Gaelic Irish) Burke (Norman) Collins (usually Gaelic Irish but also English) Campbell (Scottish but also Gaelic Irish - Mac Cathmhaoil) Clarke (usually Gaelic Irish from O Cleary but also English and Scottish) Johnson (usually Scottish but also from the Gaelic Irish McShane) Hughes (often English or Welsh but also a form of the Gaelic Irish O hAodha - Hayes) (O)Farrell (Gaelic Irish) Fitzgerald (Norman) Browne (Norman) Martin (Norman) Maguire (Gaelic Irish) (O)Nolan (Gaelic Irish) (O)Flynn (Gaelic Irish) Thompson (Scottish and English) (O)Callaghan (Gaelic Irish) (O)Donnell (Gaelic Irish) (O)Duffy (Gaelic Irish) (O)Mahony (Gaelic Irish) (O)Boyle (Gaelic Irish) (O)Healy (Gaelic Irish) (O)Shea (Gaelic Irish) White (usually English sometimes used for several different Gaelic Irish names) (Mc)Sweeney (Gaelic Irish) Hayes (usually Gaelic Irish from O hAodha sometimes Norman e.g. de la Haye) Kavanagh (Gaelic Irish) Power (Norman) 55. (Mc)Grath (Gaelic Irish) 56. (O)Moran (Gaelic Irish) 57. (Mc)Brady (Gaelic Irish) 58. Stewart / Stuart (Scottish) 59. (O)Casey (Gaelic Irish) 60. (O)Foley (Gaelic Irish) 61. Fitzpatrick (Gaelic Irish) 62. (O)Leary (Gaelic Irish) 63. (Mc)Donnell (Scottish gallowglass in Antrim and Gaelic Irish in Thomond and west Ulster) 64. (O and Mc)Mahon (Gaelic Irish - two distinct septs of McMahon and 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. 71. 72. 73. 74. 75. 76. 77. 78. 79. 80. 81. 82. 83. 84. 85. 86. 87. 88. 89. 90. 91. 92. 93. 94. 95. 96. 97. 98. 99. at least one O Mahon) (O)Donnelly (Gaelic Irish) (O)Regan (Gaelic Irish) (O)Donovan (Gaelic Irish) Burns (usually Scottish in Ulster but also used for Gaelic Irish names including Byrne, Beirne, etc.) (O)Flanagan (Gaelic Irish) (O and Mc)Mullan (Gaelic Irish and Scottish - from McMillen) Barry (Norman) (O)Kane (Gaelic Irish) Robinson (English) Cunningham (usually Scottish sometimes Gaelic Irish O Cuinneagain) (O)Griffin (Gaelic Irish) (O)Kenny (Gaelic Irish) (O)Sheehan (Gaelic Irish) (Mc)Ward (usually Gaelic Irish sometimes English) (O)Whelan (Gaelic Irish) Lyons (Gaelic Irish with multiple origins, also English and Scottish) Reid (usually English but also the anglicised forms of several Gaelic Irish surnames) Graham (usually Scottish but also the anglicised forms of several Gaelic Irish surnames) (O)Higgins (Gaelic Irish) (O)Cullen (Gaelic Irish) (O and Mc)Keane (Gaelic Irish) King (usually English but also the anglicised forms of several Gaelic Irish surnames) (O)Meagher / Maher (Gaelic Irish) (Mc)Kenna (Gaelic Irish) Bell (Scottish and English) Scott (mainly Scottish sometimes English) (O)Hogan (Gaelic Irish) (O)Keeffe (Gaelic Irish) Magee (mainly Gaelic Irish sometimes Scottish) (Mc)Namara (Gaelic Irish) (Mc)Donald (usually Scottish but sometimes from the Gaelic Irish McDonnell) (Mc)Dermot (Gaelic Irish) (O)Moloney (Gaelic Irish) (O)Rourke (Gaelic Irish) (O)Buckley (mainly Gaelic Irish, O Buachalla, but also English) 100. (O)Dwyer (Gaelic Irish) Top