The literary and artistic merit of the graphic text as new textual genre

advertisement

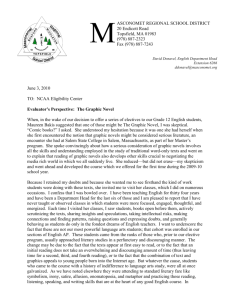

The literary and artistic merit of the graphic text as new textual genre and hybrid literary/artistic form Catherine Beavis, Griffith University Graphic novels as sophisticated multimedia form The emergence of the graphic text over recent decades as an increasingly significant literary and artistic form has led to considerable scholarly interest in many quarters. As a genre, it combines visual and verbal modes to create rich and complex narratives, managing sequence, space and time in ways that require significantly different forms of ‘reading’ than do primarily verbal forms, such as the novel. Graphic novels are one of a number of multimodal genres, where more than one meaning-making mode − writing, image, movement, sound etc. − is used to create the narrative world. Words, images, panels and the spaces between them are the core components of the genre, with graphic novels calling on the qualities or ‘affordances’ of print and drawing, in a sometimes parallel, sometimes seamless combination, where multiple forms of ‘reading’ are required. The specific qualities of the genre − the modes and affordances − enable forms of representation and storytelling that share family resemblances with older form, but function differently. Graphic novels are quintessentially multimodal, and require new ways of reading that call on conventions associated with both visual and verbal modes. It is the combination of text and image, words and lines, sequential panels and the ways in which the panels themselves are used, together with the spaces between them, that give graphic novels their particular power. In the hands of accomplished artists and writers, a ‘canon’ of graphic novels and graphic narratives is developing. Reflecting the subtlety and status of this work, the form has prompting growing interest, requiring what has been described as a ‘disciplinary reconfiguration’ (Gardner and Herman, 2011) among fields dealing with representation in various forms. To explore and understand graphic novels, perspectives are drawn from the fields of literature and art, fiction, narrative and history, each having something to contribute, and with graphic novels in turn prompting a re-examination of these categories. Before examining the ways in which graphic novels work as multimodal genre, however, and how the intersections between visual and verbal and the organisation of time and space work to create narrative, matters of definition and genealogy should be raised. Nomenclature and Definitions From a literary studies perspective, definitions of the graphic novel, or how to name what is currently understood by that term, are not yet settled. The challenge is to find a term that both encompasses the range of literature created in this form, including 1 nonfiction as well as fiction narrative forms, and acknowledge the comic book origins of the genre, with the attendant risk that to do so in some quarters will be seen to devalue the genre. The Oxford English Dictionary (1993) defines the graphic novel as ‘a narrative work in which the story is conveyed to the reader using sequential art either in an experimental design or in a traditional comics format’. Similarly, Tabachnick draws attention to form and provenance in defining the graphic novel as ‘an extended comic book that treats nonfictional as well as fictional plots and themes with the depth and subtlety we have come to expect of traditional novels and extended nonfiction texts’ (2009, p. 1). As some of the most sophisticated texts are concerned with the representation of historical and political events, the term ‘graphic narrative’ is sometimes used. The term ‘comics’, as a singular noun, is also used by many in the field, to refuse distinctions between high and low culture, and incorporates the full spectrum from popular comic strips to complex literary/aesthetic forms. Key characteristics The graphic novel or narrative: (i) is a hybrid word-and-image form in which two narrative tracks, one verbal and one visual, render temporality spatially (ii) moves forward in time through the space of the page, through its progressive counterpoint of presence and absence (iii)comprises packed panels (also called frames) alternating with gutters (empty space) (iv) is highly textured in its narrative scaffolding (v) does not blend the visual and the verbal − or use one to simply illustrate the other − but is rather, prone to present the two non-synchronously (vi) requires the reader to not only fill in the gaps between the panels, but to also work with the often disjunctive back and forth of reading and looking for meaning (adapted from Chute, 2008, p. 4). Genealogy Genealogies of the graphic novel variously emphasise longstanding early forms of pictorial sequential storytelling, such as some Egyptian hieroglyphic sequences, the Bayeux tapestry, Trajan’s column, and pre-Columbian picture manuscripts; etchings, paintings and other forms in which a sequence of images are presented in narrative form, such as Blake’s poems and drawings of heaven and hell, etchings and paintings by Hogarth; and the more narrowly specific evolution of comic books in Europe, America and the UK, traced back to the ‘picture novels’ developed by Topffer in the early 19th century. At least three different traditions of the genre are discussed: the French/European, as epitomized by Asterix and The Adventures of Tintin, the manga tradition in Japan, and American popular culture, including the superhero form. While some seek to distance graphic novels from these antecedents, others see this heritage as an important component of the form; the ways it works and the ways it is understood. Humour and the mass media provenance, and the expectations they marshal, remain important elements in the ways in which graphic texts are approached by creators and readers alike. ‘In the graphic narrative’, according to Chute, ‘we see an embrace of 2 reproducibility and mass circulation as well as a rigorous, experimental attention to form as a mode of political intervention.’ (Chute, 2008, p. 10) Multimodality and elements of the genre To be fully literate in the contemporary world entails being literate with respect to both print and multimodal forms, and to have the capacity to be able to both create and analyse multimodal texts at a high level. Words and images have different logics, and the design or organisation of page and screen work differently: ‘The logic of (alphabetic) writing’, argues Kress, ‘is the logic of time and sequence; the logic of image, on the other hand, is the logic of space and simultaneity’ (p. 140). Where ‘the elements of writing unfold in time and are related by sequence … the elements of the image are present in spatial arrangements, and they are ordered by spatial relations’ (Kress, 2003, p. 140). Pages in graphic novels and graphic narratives are made up of words and images within panels, the panels themselves, and the gaps or spaces formed between panels. In graphic novels, word and image work together, but their integration entails something other than the parallel existence of these two logics separately. To the key elements of words and images, McCloud (1993) adds ‘time’, as the combinations and layers of image and words within and between panels use space and relationships to create a sense of sequencing and time. This is part of what makes graphic narratives unique. No other medium, as Crutcher (2011) argues, ‘can present time in the myriad ways’ the genre makes possible. Single frames ‘may or may not depict singular moments, illustrators can adjust time through spacing and framing and detail.’ Further, ‘pages can exist in multiple temporal places at once,’ and ‘motion can be represented … as vividly as in film’ (Crutcher 2011, p. 55-6). The medium ‘offers range and versatility with all the potential imagery of film and painting plus the intimacy of the written word’ (McCloud 1993, p. 212). Readers build connections between the panels, with these elements (words and images, panels and spaces, the organisation of the page) together using space to create a sense of sequence or time, through a variety of representational means. In seeking to determine what distinguishes the genre from all other forms, from a visual arts point of view, intrinsic to the ‘drawn’ nature of the narrative, attention constantly comes back to two key factors – the spaces between the panels, and the line. The most powerful examples of the genre use these qualities to create rich and nuanced narratives unreproducible in other forms. As Crutcher (2011) argues, they mean that graphic novels ‘can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels or traditional films, and therefore deserve critical and scholarly attention’ (p. 69). This complexity comes through: (a) the medium: the way writers, inkers, colorists and others involved in the production of a graphic novel impose control, create layering, build atmosphere, and highlight artistic craft; b) stories: how graphic novels work well beyond the superficial, delving into the human condition, political and cultural subversion, psychology, and the duality of the persona; and c) character: creating and sustaining icons that cross myriad temporal, visual, and setting ranges while paradoxically remaining coherent’ (p. 69). 3 Three examples 1. Atmosphere, the aberrant and the line The Japanese manga novel Adolf deals with militarism and nationalism in Japan and Germany prior to World War II. The role of the line is evident in creating an atmosphere of sinister menace, through the driving rain, the darkness and the shadows. Also in evidence are unexplained non sequiturs between each panel − broken shop signs, a body huddled in a doorway, an anonymous well-dressed figure, his face masked by the umbrella, his unexplained presence in the rain. The reader takes all this in via a complex visual process: filling gaps, building connections, asking questions and incorporating unexpected elements as best they may, taking in the mood of bleakness, dereliction and decay (Adams 1999, p. 71). 2. Aesthetic conventions and visual metaphor 4 Figure 1: Barefoot Gen: The Day After by Keiji Nakazawa (2004, p. 181). Barefoot Gen, another Japanese manga novel, is set in the period immediately following the bombing of Hiroshima, describing events from the perspective of a child. The drawing of the child incorporates familiar elements from the kiwame (cute) aesthetic of much Japanese popular culture, with wide eyes and Disneyesque drawings, but a very different sensibility that eschews sentimentalism and presents the children as persevering in the face of the bombing of Hiroshima, the incomprehensibility of what has happened, and the seeming impossibility of rebuilding any form of society. Of particular interest is panel 2 (see Figure 1), and the image of the sun − its simplicity and burning intensity linking it simultaneously to the atomic explosion that has caused this devastation (Adams 1999, pp. 72-3). The seeming non sequitur between this panel and those around it intensifies the complexity of both narrative and mood, forcing the reader to actively ‘fill in’ connections between them all, in their own creation of the narrative. 3. Competing and non-synchronous narratives: the multilayering of time Spiegelman’s Maus II epitomises the ways in which panels weave together multiple narratives, contexts and times. ‘Speigelman toys with narrative expectations of temporal moments’, Chute argues. ‘As historical enunciation weaves jaggedly through paradoxical spaces and shifting temporalities, comics − as a form that relies on space to represent time − becomes structurally equipped to challenge dominant modes of storytelling and history writing’ (p. 456). ‘In competing and nonsynchronous narrative layers of comics [Speigelman] creates an intense level of self-reflexivity’ (p. 457). The form is ‘a structurally layered and double medium that can proliferate historical moments on the page, (… concentration camp corpses wordlessly invade a present day SoHo studio)’ (p. 459). The suitability of graphic novels for study as a new form of literary representation in multimodal form in senior secondary English curriculum As the field has matured, a canon of sophisticated, multilayered graphic novels and narratives has developed, well worthy of study at senior secondary English alongside other forms of literature in more familiar print and multimedia genres. By virtue of its capacity to represent time and motion, in single moments or simultaneously, to draw on the advantages of both print and visual forms to mobilise the qualities of each, to reference intertextually, and to incorporate other media such as maps, photographs, narrative and testimony in representing, for example, history. In its richest form the genre has developed a number of aesthetically innovative and highly sophisticated multidimensional narratives that deal with complex matters in nuanced and multilayered ways − and all this within and between the panels, and the basic two-dimensional layout of the page. References Adams, J 1999, ‘Of Mice and Manga: Comics and Graphic Novels in Art Education’, Journal of Art and Design Education, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 69-75. Chute, H 2008, ‘The Changing Profession, Comics as Literature: Reading Graphic Narrative’, PMLA: Publications for the Modern Language Association of America, Vol. 123, No. 2, pp. 452-65. 5 Crutcher, P 2011, ‘Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium’, The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 53-72, 55-6. Gardner, J & Herman, D 2011, ‘Graphic Narratives and Narrative Theory: Introduction’, SubStance, vol. 40, no. 124, pp. 3-13. Kress, G 2003, ‘Interpretation or design? From the world told to the world seen’, in Styles, M & Bearne, E (eds.) Art, Narrative and Childhood, Trentham Books, pp. 13753, Stoke on Trent. McCloud, S 1993, Understanding Comics: the invisible art, Harper Collins/Kitchen Sink Press, New York. Nakazawa, K 1989, Barefoot Gen: Life After the Bomb. A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima, vol. 3 of Barefoot Gen, New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island. Tabachnick, S 2009, Teaching the Graphic Novel, The Modern Language Association of America, New York. Speigelman, A 1991, Maus II: A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles Began. New York: Pantheon. Tezuka, O 1996, Adolf: An Exile in Japan, Cadence Books, Canada. 6