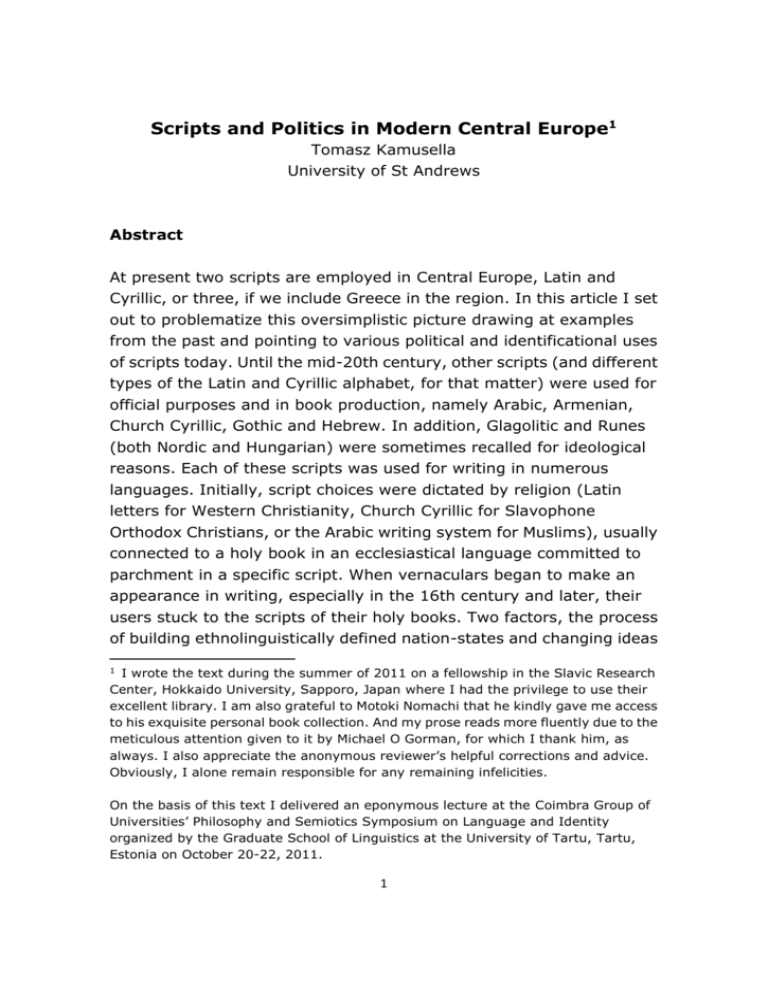

Coimbra Group of Universities

advertisement