- SOAS Research Online

advertisement

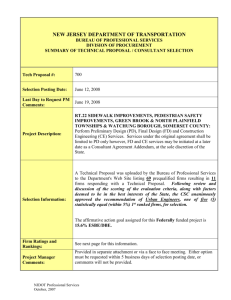

Explaining Partial Privatization of Public Service Provision: The Emergence of Mixed Ownership Water Firms in Italy (1994-2009) Dr Alberto Asquer Draft Abstract Within the area of study of privatization, some attention has been placed on the emergence of mixed public-private ownership firms for the provision of public services. Mixed ownership firms pose an important theoretical issue, i.e., why do governments open up part of their ownership of public service providers to private operators and investors rather than giving up full ownership of public service providers or establishing a contractual relationship with the private partner? This paper aims to address this issue by analyzing the case of the emergence of mixed ownership firms for the provision of water services in Italy. The analysis of the case shows that partial privatization of public service providers is especially related to characteristics of the historical and institutional context as well as to features of the privatization policy process. Key words: Privatization, mixed ownership, water sector. 1 Explaining the Partial Privatization of Public Service Provision: The Emergence of Mixed Ownership Water Firms in Italy (1994-2009) INTRODUCTION A growing amount of scholarly attention has been recently devoted to the emergence of mixed public-private ownership firms for the provision of public services (Albalate et al., 2012a, 2012b; Bel and Fageda, 2010; Boardman and Vining, 1998; Bognetti, and Robotti, 2007; Brandsen and Karré, 2011; Cruz and Marquez. 2012; Marra, 2006, 2007). In a type of scenario, mixed ownership firms arise as a temporary arrangement within the privatization of government-owned companies, when the government sells non-controlling stakes of the company first and the rest of the shares later on (Gupta, 2005). Such mixed ownership firms exists provisionally during an intermediate stage between full public ownership and final full privatization. In another type of scenario, instead, mixed ownership firms are established as an enduring form of public-private partnership. Such mixed ownership firms or 'institutionalized public-private partnerships' (iPPPs; Cruz and Marques, 2012; Marques and Berg, 2011) originate from a deliberate design for organizing the provision of public services through firms that are jointly owned by public authorities and private operators or investors. Why do governments open up part of their ownership of public service providers to private operators and investors rather than giving up full ownership of public service providers or establishing a contractual relationship with the private partner? This paper aims to address this issue by analyzing the implementation phase of the policy cycle to privatize Italy's (drinking and waste) water sector in the period 1994-2009. Moving from status quo conditions that included diffuse public ownership of water firms and high fragmentation of the water industry, the implementation of the privatization of the water sector in Italy led to a massive consolidation of water service providers and to some partial privatization of local government-owned water firms. At the end of the implementation episode, about two thirds of Italy's water sector was retained under full public ownership, but about one fourth of the country's water service providers were partially opened to private operators (including major French water multinationals) and investors. In a very few cases only were water franchises awarded to fully privately owned companies. The analytical issue at stake, then, is why were water services privatized to mixed ownership firms in a minor part of the country's water industry. The analysis of the case will contrast and compare the trajectory that led to the formation 2 of mixed ownership firms in some parts of the country with the one that resulted in the maintenance of full public ownership water service provision in the rest of Italy. The comparative analysis of reform implementation trajectories is conducted in a processual approach, a method of analysis that is especially attentive to the role of time, path dependency, and changing context conditions in affecting the path and outcome of public policy (Kingdon, 1984) and organizational (Pettigrew, 1997) processes. The case study will show that the emergence of mixed ownership water firms in Italy can be explained by the joint combination of initial conditions of the water industry, changed features of the water reform content, and characteristics of the policy process (especially, the diffusion of ideas about partial privatization drawn from early experiences of the water reform implementation). The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Next section will review the scholarly literature on privatization, with particular attention to research works that especially have been concerned with the political economy of the policy-making stage of privatizing public service providers. Section three will present the research design of this study. The fourth section will narrate the implementation of the privatization of the water sector in Italy in the period 1994-2009. Section five will analyze and discuss the case and the research findings. Finally, the last section will draw the conclusions of this study. THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF (PARTIAL) PRIVATIZATION There is a vast literature on privatization, broadly defined as the deliberate sale by a government of corporate entities (state-owned enterprises or SOEs) or public assets (Bös, 1991; Megginson and Netter, 2001; Vickers and Yarrow, 1988). Most theoretical and empirical works have focused on the rationales, forms, and performance effects of privatization in general (Clifton et al., 2006; Donahue, 1989; Feigenbaum et al., 1998; Kolderie, 1986; Lundqvist, 1988; Sappington and Stiglitz, 1987; Starr, 1988; Vickers and Yarrow, 1988, 1991; Yarrow et al., 1986). Relatively less attention has been placed, instead, on the particular type of (partial) privatization that takes place when the government deliberately retains a share of ownership of the firms or assets that have been put on sale. Yet, mixed ownership firms pose several issues, especially related to the governance and to the performance effects of such form of enterprise, that call for attentive scholarly work. From an economic perspective, partial privatization can be conceived as a solution to the problem of designing efficient organizations. Works done within the scholarly literature on transaction cost economics (Williamson, 1991, 1985, 1975), in particular, highlighted that 3 organizational and governance forms are selected in order to minimize the cost of ‘frictions’ in contractual relationships that especially arise from information asymmetries, asset-specificity, bounded rationality, and moral hazard. Mixed ownership firms constitute a ‘hybrid’ institutional arrangement that provides a framework for organizing transactions while minimizing shirking (minimizing efforts unless properly supervised) and cheating (inflating prices and/or reducing quality) costs (Hennart, 1993). For example, Bel and Fageda (2010, 2008) showed that mixed ownership firms are established in response to pragmatic concerns when public authorities deal with contradictory pressures related to transaction cost considerations, financial constraints, and private interests. Warner and Bel (2008) related the presence of ‘hybrid public/private firms’ in Spanish municipalities to the benefits that such firms receive from both market engagement and economies of scale available under monopoly production. Marra (2007) showed that the establishment of mixed ownership firms allows the public owner to gather more information about the management of the partially privatized firm than under full privatization and contractual or regulatory arrangements. Brown and Potoski (2003) offered a transaction cost economics explanation of the choice of governments on how to deliver services to citizens. Other works especially focused on the role of political factors in the making of mixed ownership firms. From a political perspective, partial privatization can be understood as a type of process related to so-called ‘pro-market’ regulatory reforms, that is, public policies that aim to enhance general welfare by exposing operators to competitive pressures (Bienen and Waterbury, 1989; Clarke, 1995; Landy et al., 2007; Suleiman and Waterbury, 1990). Of course, the privatization of public service providers, by itself, does not necessarily imply any increase of competitive pressures, if the effect of privatization on the industrial structure of the reformed sector is merely the one to replace a public monopoly with a private or mixed ownership one. ‘Pro-market’ regulatory reforms should typically contain policy measures that liberalize access to the market and provide measures against collusive agreements and the abuse of dominant positions. ‘Pro-market’ policies, however, may also take the form of institutional and regulatory arrangements that include some form of market-based discipline on the conduct of public service providers. Mixed ownership firm can provide such sort of market-based pressure, because the private partner should expect that the firm attains a level of profitability that is higher than alternative forms of investments with commensurate risk, else private capital could be more profitably employed. Several works highlighted the role of political factors in the making of mixed ownership firms. Early studies by Brooks (1987) and Heald (1988), for example, highlighted that the creation of mixed ownership firms is driven by political considerations that especially relate to the pursue of public policy 4 objectives. Wollmann (2012, 2010, 2004, 2000) highlighted similarities and differences in privatization trends – including the creation of mixed ownership firms – across countries that especially included the role of political and ideological inclinations. RESEARCH METHOD This paper aims to address the question of what accounts for the creation of mixed ownership firms for the provision of public services. This question is tackled through the case study (Ragin and Becker, 1992; Stake, 1995; Yin, 2003) of the implementation episode of the policy cycle to privatize Italy's (drinking and waste) water sector in the period between 1994, when a policy reform provided the re-regulation, liberalization, and privatization of water services in the country, and 2009, when the water reform was substantively reversed. In 2009, a public protest mounted against legislation that mandated to privatize public sector water firms that did not attain financial self-sufficiency. The protest resulted in a plebiscite (held in 2011) that repealed the rules that allowed the management of local public services to be entrusted to the private sector and the regulation that determined the tariff for water supply (that included a return on capital invested). Other legislation passed in 2009 abolished the local water regulatory authorities. The selection of the case is justified by the distinguishing features of the case path and outcome – in particular, the presence of within-case variation between paths and outcomes of the reform implementation process across the country. The emergence of mixed ownership water firms took place during the period 2001-2003, while in the periods 1994-2001 and 2003-2009 local governments generally retained full ownership of water firms. In addition, the episode contains a ‘sub-case’ of trajectory of partial privatization of water services in the area of Alto Valdarno (Tuscany region), where local governments partially privatized their water firms in the period 19941999, i.e., at much faster pace than elsewhere in the country. The analysis will take advantage of these features of the episode for comparing the trajectories of the privatization process across time (i.e., the partial privatization in the period 2001-2003 with respect to the preservation of full public ownership in 1994-2001 and 2003-2009) and space (i.e., the partial privatization in Alto Valdarno in 1994-1999 with respect to the rest of the country in the same period). Data were collected from primary, secondary, and tertiary sources. Primary sources included parliamentary minutes, official reports and other documents issued by the national water regulatory agency (Comitato di Vigilanza per l'Uso delle Risorse Idriche or Supervising Committee on the Use of Water Resources), and 20 interviews with informants based in the Supervising Committee on the Use of Water Resources (4), in the local regulatory authorities (11), in water firms (3), in the 5 association of water firms Federgasacqua (1), and in the research centre Istituto Ricerche Sociali (1). Secondary sources included reports issued by the water research centers Proaqua, Astrid, and Utilitatis, proceedings of the yearly conferences ‘H2Obiettivo 2000’ organized by the water firms' association Federgasacqua (renamed Federutility from 2005), and articles from the business press Il Sole 24 Ore (546 total). Tertiary sources included various scholarly works done on the reform of water services in Italy (Anwandter and Rubino, 2006a, 2006b; Bognetti and Robotti, 2007; Citroni and Lippi, 2006; Citroni et al., 2007; Gilardoni and Marangoni, 2004; Guffanti and Merelli, 1997; Lippi et al., 2008 ; Marra, 2006, 2007; Massarutto, 2005, 1993). The Appendix provides more detailed information about documentary and interview sources. The analysis of data followed a processual approach for explaining the path and outcome of the privatization process (George, 1979; Bennett and George, 1997; George and Bennett, 2005; Kingdon, 1984; Pettigrew, 1997). A processual analytic method enables us to develop explanatory arguments that are especially attentive to time, path dependency, and changing context conditions (Mahoney, 2000; Pierson, 2000, 2004; Barzelay and Gallego, 2006). A distinguishing feature of this approach is the use of social mechanisms (Hedström and Swedberg, 1998; McAdam et al., 2001) as theoretical resources for explaining empirical instances of the process under consideration. Variously conceived as interpretations (Schelling, 1998) or hypothetical causal models (Gambetta, 1998) or plausible hypotheses that could be the explanation of some social phenomenon (Hedström and Swedberg, 1998) or frequently occurring and easily recognizable causal patterns (Elster, 1998) about the behavior of entities at different levels (e.g. individuals) rather than the main entities being theorized about (e.g. a group or a social process), social mechanisms provide (either in isolation or in concatenations; Gambetta, 1998) hypothesized social interactions which are believed to cause the observable effects that are cast in the role of explananda. Within the present case study, social mechanisms have been employed to help developing, in analytical inductive approach, a historically grounded theoretical account of the partial privatization process. The present work, therefore, falls into the category of ‘heurisitc’ case study within the classification proposed by Thomas (2011) (that also included atheoretical, disciplined-configurative, theory testing, plausibility probe, and crucial case studies). THE PRIVATIZATION OF THE WATER SECTOR IN ITALY (1994-2009) Initiating the privatization process (1994-2001) In late 1993, the Parliament of Italy passed a legislation containing the reform of the country's water sector (Act 36/1994). The reform mainly intended to improve water sector 6 performance (in such terms as cost efficiency and service quality) by consolidating a very fragmented industry (that counted about 23,500 operators in the country), eliciting competitive pressures for the award of water franchises, and attracting private operators and investors. The water reform provided that the regions passed legislations that defined the boundaries of new water administrative jurisdictions (called Ambiti Territoriali Ottimali or Optimal Territorial Areas, henceforth OTAs) and the specification of various details of the new regulatory system. Additionally, local governments were required to establish local regulatory authorities (Autorità d'Ambito or OTA Authorities) that would award water franchises to either mixed ownership firms or to business companies selected through tender offer competitions. After the water reform came into force, sub-national governments spent several years to set up the new regulatory system, with the effect that the privatization of water service provision was considerably delayed. In part, the delay to implement the water reform originated from a sense of discontent towards the ‘marketization’ of water that was diffused among part of the population and championed by leftist parties. In part, obstacles to water reform implementation also related to the resistance of local politicians to privatize the water firms, because control of water service provisions often enabled them to exert influence on water-related jobs and public contracts and, therefore, to cultivate the electoral support of local constituencies. This view was illustrated by Francesco Bosco, manager of ACEA, in this way: “The water reform affected the vicious circle between politicians, water firms' managers, and the voters. The mayor loses power if water is managed by someone else outside the local government, because water has always been important for electoral purposes. We can recall a movie, 'The Postman' [1994], where a local politician gains the votes for his election by promising to bring water supply to the town. [Local government-owned] water firms were afraid to lose their role and not to be protected, while local politicians perceived that the water reform could spoil them of their power” (interview, September 2001). Part of the water sector, however, was favorably inclined towards the implementation of the water reform. Since early 1990’s, several local government-owned public service firms had been reincorporated as municipal companies after the central governments passed legislation that prohibited public funding of their deficits. Within these municipal companies, executives and water professionals developed a shared view that water services could be efficiently managed with an ‘entrepreneurial’ spirit. This attitude circulated and consolidated through the network of water 7 policy experts that had formed around the national association of water and gas utility firms, Federgasacqua, especially on the occasions of the yearly conferences ‘H2Obiettivo 2000’. Some local politicians openly supported the reorganization of water service providers, such as, for instance, Lido Scarpetti, mayor of Pistoia, who argued: “We aim to pool together the resources and managerial capabilities [of local government-owned water firms] that we accumulated in the past, in order to enter the market in a strong position, and to be ready for the opportunities that arise from the institutional changes [in the water sector]. Nowadays there is a trend towards overcoming particularism and achieving economies of scale in order to optimise costs and services” (Il Sole 24 Ore, 24th April 1997). Establishing a mixed ownership water firm in Alto Valdarno During the period 1994-1999, one mixed ownership water firm only was established by local governments located in the area called Alto Valdarno in Tuscany. The partial privatization of water services in Alto Valdarno originated from negotiations that had been conducted in 1990 by the gas firm Coingas, owned by the municipality of Arezzo, and various local governments of the same area for merging with other municipal companies that operated in the gas and water industries (Caselli and Peruzzi, 1996; Lobina, 2005). Having gained the support of the center-left parties which backed the city executive, in October 1992 Coingas submitted a plan which provided that the firm would be reincorporated as a business company and would be assigned the water franchise of Arezzo (that directly managed water services at that time) and of 24 other neighboring local governments. Support for the Coingas plan dissolved in 1995 after the formation of a new centerleft coalition executive in Arezzo, chaired by the mayor Paolo Ricci. Following the political orientation of the regional branch of the leftist Democratici di Sinistra party (DS) at that time, Ricci rather favored the formation of mixed ownership firms for the management of local public services. After the Coingas plan was overruled on the basis of the lack of transparency related to crosssubsidization between gas and water activities and the firm's modest experience in managing water services, in February 1996 the city council of Arezzo approved Ricci's proposal to establish a local government majority-owned water firm, called Nuove Acque. In July 1997, Nuove Acque was awarded the water franchise by the OTA Authority of Alto Valdarno and local governments of the area decided to tender out a minority share (46%) of this company to private operators. On 21 st March 1999, finally, the minority share of Nuove Acque was assigned to a consortium of companies led by Suez-Lyonnaise des Eaux. 8 The award of water franchises to mixed ownership firms (2001-2003) In December 2001 the Parliament passed a reform (Act 448/2001) that provided the general rule that local public services should be contracted out to private operators through tender offer competitions. Special provisions, however, allowed to postpone tender offer competitions in the water sector up to 10 years, if particular conditions (such as merging water firms into larger operators and opening up ownership to private operators or investors) were met (Petretto, 2001). After the Parliament passed the 2001 reform, some local governments (especially, those neighboring Alto Valdarno and that had been preparing to implement a partial privatization scheme similar to the one of Nuove Acque), rushed to make the OTA authorities award the water franchises to their water firms within the few weeks’ time before the 2001 reform came into force. In this way, local governments could bypass the requirement to award water franchises through tender offer competition imposed by the 2001 legislation. After the 2001 local public services reform came into force, local governments started to restructure local water service arrangements with the intention of postponing tender offer competitions whenever possible. First, local governments made their water firms merge and reincorporate in order to match the size and other requirements set by the legislation, then they made the OTA authorities award water franchises to the local government-owned merged firms, and finally they made the water firms partially open up their ownership to private operators or investors. When following this partial privatization scheme, local governments also realized that, far from completely giving up their influence on the water industry, they could retain considerable sway by appointing the company management and maintaining a strong voice on key organizational processes. This view was succinctly expressed, for example, by Alessandro Antichi, mayor of Grosseto, in this way; “We mayors know well that a tight control on third entities, such as the companies which provide local public services, is actually more effective than the one we have on our own managers, that we find in a local authority because they won a public selection, they chair a division which is only respondent to them, and, as a matter of fact, for us it is much easier to manage through the companies than through the managers [of the local governments]” (Federgasacqua conference, Trieste, 24-26 September 2003). 9 Awarding water franchises to full public ownership firms (2003-2009) In September 2003, the central government passed another reform (Legislative Decree no. 269, later partially amended by Act 350/2003) that restated that local public services should be contracted out to private operators through tender offer competitions. The reform also allowed, however, that franchises of local public services could be legitimately awarded either to mixed ownership firms, where the private partner had been selected through tender offer competitions, or to firms fully owned by local governments, provided that these firms deliver most of their services to the same local governments, and that local governments exercise on these firms a control as tight as the one exerted on their own divisions (so-called ‘in house’ arrangement). After the 2003 reform came into force, several OTA authorities started awarding water franchises to ‘in house’ firms, that, albeit established as business companies, secured local governments' close control on local water industries. Such ‘formal privatization’ scheme was exploited by local governments as a way to bypass the tender offer competition rule or the requirement to partially open the ownership of the water firms to private operators or investors. The implementation of the water reform led, by late 2000's, to some degree of industrial reorganization and privatization of the water sector. A survey of the water sector in 2009 showed (Table 1) that water franchises had been awarded in about two thirds of the OTAs (67 out of 92), and that most of them had been granted to ‘in house’ firms (i.e., without opening up ownership to private operators or investors and without any tender offer competition). About one fourth of water franchises, however, had been awarded to water firms whose ownership had been partially opened up to private operators (in the form of minority share of mixed ownership firms) or investors (in the form of share ownership of companies floated in the stock exchange) during the period 2001-2003. < insert Table 1 about here > EXPLAINING THE EMERGENCE OF MIXED OWNERSHIP FIRMS IN THE WATER SECTOR IN ITALY Before analyzing the trajectory of the water reform implementation, we briefly discuss how the decision to privatize water service provision was made. An important factor, in this respect, is the regulatory governance system of the OTA authorities. Local governments established the OTA authorities as organizations that they owned and controlled, rather than as independent agencies. By designing the local water regulatory authorities in such a way, local governments anticipated that they could retain influence on the decisions made by the OTA authorities, including those related to 10 how water services would be privatized. Neither the water reform statute nor general legislation on the provision of local public services mandated that the OTA authorities should be established as independent agencies – a design option that could have made the OTA authorities less exposed to local governments' influence, but that never gained any serious consideration within local governments' political circles. Why, then, did local governments not make the OTA authorities award the water franchises in the first period of the episode? In order to answer this question, we take into consideration the role played by initial conditions of the water policy subsystem (diffused local government ownership of water service providers and local governments' ownership and control of the OTA authorities), features of the policy content (especially the provisions that each OTA authority would award water franchises to one water company only), and features of the policy process (the provisions that local governments were required to agree on the establishment of the OTAs before the regions could pass the legislations for enforcing the water reform at the regional level). In explaining how these conditions resulted in the stability of the water ownership structure after the enactment of the reform, an important role could be played by the mechanism of sequential attention to goals. Sequential attention to goals (Cyert and March, 1963) holds that, because of cognitive limitations and conflicting interests, problem-solving in organizational contexts is mainly driven by ‘satisfying’ rather than ‘optimizing’ criteria, including a stepwise approach to complex issues. Indeed, features of the policy content and the policy process made local governments face the complex issue of attaining multiple goals (i.e., consolidating water services, centralizing regulatory functions, and privatizing the water industry) under conditions that included deep interdependences between each component part of the water reform and the several actors involved. Cognitive and organizational factors, therefore, may help explaining local governments' delay to execute the policy reform mandate in the years immediately after its coming into force. While the implementation of the water reform generally faltered in the country, the OTA authority of Alto Valdarno carried out the partial privatization of water services in relatively short time. In this sense, part of Tuscany deviates from the general ‘inertia’ pattern in the country during this period. In exploring why this within-case variation took place, we especially take into considerations initial conditions of the water policy subsystem in Alto Valdarno, that included previous events that had led to the formation of an agreement between local governments located in this part of Tuscany over the consolidation of water and gas services in one firm only and over the partial privatization of the local municipal company. This event resulted in conditions that contributed favoring the partial privatization of water services in this part of Tuscany. Initial 11 conditions also included particular features of the local water industry, in the form of the presence of municipal companies for the delivery of local public services. As an organizational form, municipal companies possess particular institutional features (such as statutory autonomy with respect to the municipal owner) the make them enjoy relatively more ‘freedom to act’ with respect to alternative entities, such as municipal departments and local government consortia. In other words, municipal departments and consortia encounter more sources of ‘institutional inertia’, in such forms as statutory or legislative constraints, that could have played against the feasibility of privatizing water services. For explaining why these conditions were conducive to the privatization of water services in Alto Valdarno, we can call into play the role of the mechanisms of organizational appropriation, understood as the exploitation of existing entities for mobilization of action (McAdam et al., 2001), and committed interpretation, conceived as the development of an open justification for one's behavior based on past public actions (Weick, 2001). The past agreement to centralize gas and water services into a municipal company provided an organizational ‘vehicle’ that local actors could appropriate for implementing the partial privatization of water services. Indeed, most of the design work for reconfiguring the provision of water services in Alto Valdarno had already been negotiated when the water reform came into force. In addition, past commitment to privatize gas and water services constituted an open policy orientation that local governments could hardly disowned or postpone. These mechanisms, then, may account for how, differently from the rest of the country, particular initial and context conditions in Alto Valdarno were especially propitious for the privatization of water services in the form of establishing a mixed ownership firm. Next issue is why the partial privatization of the water services progressed in the period 2001-2003. The explanation for this part of the water reform implementation trajectory calls into play the role of changed context conditions (especially, features of the 2001 legislation) and initial conditions (especially, the presence of municipal companies for the provision of water services). In order to explain this part of the trajectory, we consider the role played by the mechanisms of attribution of opportunities and threats and of network diffusion. The 2001 legislation provided local governments with the opportunity (McAdam et al., 2001), in the form of special provisions for the water sector, to retain influence on the local water industries. This opportunity, however, could be hardly exploited without the propelling role of the diffusion of ideas about the beneficial effects of the partial privatization scheme. Sources of resistance against the privatization of water services were partially overcome because of changed beliefs towards the expected consequences of privatizing water services, which were triggered by the diffusion of ideas within the national 12 network of water policy professionals. In general, the mechanism of network diffusion (Hedström and Swedberg, 1998) refers to how actors' beliefs are affected by perception of the behavior of others. In situations where consequences of actions are uncertain, evidence of what other actors do signals to others the value or necessity of such actions, so that others are induced to behave accordingly. Water policy professionals may have helped overcoming cognitive and organizational barriers to accept the partial privatization scheme, especially by spreading evidence of early partial privatization on the occasion of the yearly conferences of the national water firms' association Federgasacqua. Finally, the last issue is why, from 2003 onwards, water services were generally awarded to ‘in house’ firms rather than privatized (an outcome that amounts to ‘formal’ rather than ‘substantive’ privatization). In order to explain this final ‘twist’ in the trajectory of the privatization episode, we again need to take into account the role played by changed context conditions (especially, features of the 2003 legislation) and initial conditions (diffused local government ownership of water firms and local governments' stakes in the water industry). The mechanisms of attribution of opportunities and threats and of certification, that consists of the validation of actors, performances, or claims from external authorities (McAdam et al., 2001), help shedding some light on how preservation of the position of incumbent water firms was attained. The 2003 legislation changed features of the policy content that local governments framed as an opportunity to retain full ownership of water firms if they were merged together in order to gain an scale adequate for proving water service in the whole OTAs). In addition, the 2003 legislation provided a source of validation of full public ownership of water service providers, that local governments conveniently invoked for blocking the privatization process. CONCLUSIONS The present case study suggests that multiple factors need to be taken into account for explaining the trajectory of the water privatization process, especially the emergence of mixed ownership firms (Table 2). The explanation for the halting part of the trajectory of the water reform implementation in the period 1994-2001 focuses on the causal role played by diffused local government ownership of water service providers, local governments' ownership and control of the OTA authorities, and reform provisions that included that each OTA authority would award water franchises to one water company only and that local governments were required to agree on the establishment of the OTAs before the regions could pass the legislations for enforcing the water reform at the regional level. The partial privatization in the period 2001-2003 is explained by the 13 joint combination of features of the water industry, changed features of the policy content brought about by the 2001 legislation, and policy feedback effects. The award of water franchises to ‘in house’ firms after 2003 is explained by taking into account the causal role played by the diffused local government ownership of water service providers, the stakes of local government in the water industry, and changed features of the policy content brought about by the 2003 legislation. Within this case study, therefore, multiple factors contribute articulating an explanation for the partial privatization of water service provision within the process of implementing the 1994 water reform. < insert Table 2 about here > With respect to existing theoretical arguments about the political economy of privatization, this study especially places importance to the combination of features of the historical and institutional context. Rather than explaining the obstacles encountered in opening up water firms to private operators or investors just on the basis of local government's interest to protect their stakes in the water industry, this case study suggests that we should pay attention to the causal role played by initial conditions, reform content features, and reform process features – including how these conditions may change over time in relation to contemporaneous events. While this case study does not deny the importance of actors' stakes and their inclination to make decisions according to canons of instrumental rationality, it also highlights that stakes and interests are not sufficient explanatory factors for the trajectory of the privatization process. If we take into account the features of the historical and institutional context, instead, we gain a better understanding of why, depending on context conditions, privatization does not take place, or it takes the form of mixed ownership firms, or it is merely conducted in the form of ‘formal’ reincorporation under companies laws while public authorities retain full ownership of the public service providers. The emergence of mixed ownership firms for the provision of public services is not limited to the water sector in Italy, of course. Instances of mixed ownership firms abound across other sectors (e.g., gas, urban waste, public transport) and countries, especially in the EU (Cruz and Marquez, 2012; Marra, 2006; Warner and Bel, 2008). In some countries, mixed ownership firms have long seized an important place within the industrial landscape of public service provision, such as the French Sociétés d’économie mixte. Other countries, instead, hold a long tradition of full local government ownership of local utilities, such as the German Stadtwerke, that seems to persist despite an apparent upsurge of mixed ownership firms (Wollmann, 2012). The issue as to whether the design of ownership structure relates to the performance effects of mixed ownership firms with 14 respect to full public ownership remains, in this respect, elusive. The findings of this study suggest, however, that historical and institutional conditions are important to account for the persistence of existing forms of ownership of public sector providers, and that deviations from established ownership patterns may be explained by particular and contingent circumstances. 15 REFERENCES Albalate, D., G. Bel and J. Calzada. 2012a. 'Governance and regulation of urban bus transportation: Using partial privatization to achieve the better of two worlds', Regulation & Governance, 6, 1, 83100. Albalate, D., G. Bel and X. Fageda. 2012b. 'Beyond pure public and pure private management models: Mixed firms in the European Airport Industry', University of Barcelona, Research Institute of Applied Economics Working Paper No. 201221. Anwandter, L. and P. Rubino. 2006a. 'Perché la finanza privata asseta il settore idrico? Sette proposte per sette regioni', Mercato, Concorrenza, e Regole, 1, 197-228. Anwandter, L. and P. Rubino. 2006b. 'Rischi, incertezze e conflitti d'interesse nel settore idrico italiano: analisi e proposte di riforma', Materiali Unità di Valutazione degli Investimenti Pubblici. Rome. Barzelay, M. and R. Gallego. 2006. 'From 'New Institutionalism' to 'Institutional Processualism'. Advancing Knowledge about Public Management Policy Change', Governance, 19, 4, 531-557. Bel, G. and X. Fageda. 2008. ‘Local Privatization, Intermunicipal Cooperation, Transaction Costs and Political Interests: Evidence from Spain’, Research Institute of Applied Economics, Working Paper 2008/04. Bel, G. and X. Fageda. 2010. ‘Partial Privatization in Local Services Delivery: An Empirical Analysis of the Choice of Mixed Firms’, Local Government Studies, 36, 1, 129–149. Bennett, A. and A. L. George. 1997. 'Process Tracing in Case Study Research', paper presented at the MacArthur Foundation Workshop on Case Study Methods, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (BCSIA), Harvard University, October 17-19. Boardman, A. E. and A. R. Vining. 1989. 'Ownership and Performance in Competitive Environments: A Comparison of the Performance of Private, Mixed, and State-Owned Enterprises', Journal of Law & Economics, 32, 1-33. Bognetti, G. and L. Robotti. 2007. ‘The Provision of Local Public Services through Mixed Enterprises: The Italian Case’, Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 78, 3, 415–37. Bös, D. 1991. Privatization: A Theoretical Treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Brandsen, T., and P. M. Karré. 2011. 'Hybrid Organizations: No Cause for Concern?', International Journal of Public Administration, 34, 13, 827-836. Brooks, S. 1987. 'The Mixed Ownership Corporation as An Instrument of Public Policy', Comparative Politics, 19, 2, 173-191. Brown, T. L. and M. Potoski. 2003. ‘Transaction Costs and Institutional Explanations for Government Service Production Decisions’, Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory, 13, 4, 441-468. Caselli, R. and P. Peruzzi. 1996. I servizi idrici: regolazione e riorganizzazione in Toscana. Milan: Franco Angeli. Citroni, G. and A. Lippi. 2006. 'La politica di riforma dei servizi idrici. Istituzioni, processi, e poste in gioco', Regione e governo locale: Le istituzioni del federalismo, 2, 239-275. Citroni, G., N. Giannelli, A. Lippi and S. Profeti. 2007. ''Chi governa l'acqua?': regolazione, potere 16 locale, e arene di rappresentanza nella governance del servizio idrico integrato', SISP Conference, Catania, September 20-22. Clifton, J., F. Comín and D. Díaz Fuentes. 2006. 'Privatizing public enterprises in the European Union 1960–2002: ideological, pragmatic, inevitable?', Journal of European Public Policy, 13, 5, 736-756. Cruz, N. and R. Marques. 2011. ‘Viability of Municipal Companies in the Provision of Urban Infrastructure Services’, Local Government Studies, 37, 1, 93–110. Cruz, N. and R. C. Marquez. 2012. 'Mixed Companies and Local Governance: No Man Can Serve Two Masters', Public Administration, 90, 3, 737-758. Cyert, R. M. and J. G. March. 1963. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. NJ: Englewood Cliffs. Donahue, J. D. 1989. The Privatization Decision. New York: Basic Books. Elster, J. 1998. 'A plea for mechanisms' in P. Hedström and R. Swedberg (eds) Social Mechanisms: An Analytical Approach to Social Theory, 45-73. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Feigenbaum, H. B., J. R. Henig and C. Hamnett. 1998. Shrinking the State: The Political Underpinnings of Privatization. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Gambetta, D. 1998. 'Concatenations of Mechanisms', in P. Hedström and R. Swedberg (eds), Social Mechanisms: An Analytic Approach to Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 102-125. George, A. L. and A. Bennett. 2005. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Gilardoni, A. and A. Marangoni. 2004. Il settore idrico italiano: strategie e modelli di business. Milan: Franco Angeli. Guffanti, L. and M. Merelli (eds). 1997. La riforma dei servizi idrici in Italia: riflessioni e spunti comparativi. Milano: Egea. Gupta, N. 2005. 'Partial Privatization and Firm Performance', The Journal of Finance, 60, 2, 9871015. Heald, D. 1988. 'The United Kingdom: Privatisation and its political context', West European Politics, 11, 4, 31-48. Hedström, P. and R. Swedberg (eds). 1998. Social Mechanisms: An Analytic Approach to Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Hennart, J.-F. 1993. ‘Explaining the Swollen Middle: Why Most Transactions Are a Mix of “Market” and “Hierarchy”’, Organization Science, 4, 4, 529-547. Kingdon, J. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston, MA: Little, Brown. Kolderie, T. 1986. 'The Two Different Concepts of Privatization', Public Administration Review, 46, 4, 285-291. Landy, M. K., M. A. Levin and M. Shapiro. 2007. Creating Competitive Markets: The Politics of Regulatory Reform. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Lippi, A., N. Giannelli, S. Profeti, and G. Citroni. 2008. 'Adapting public-private governance to the local context', Public Management Review, 10, 5, 619-640. Lobina, E. 2005. D11 Watertime case study: Arezzo, Italy. www.watertime.net. 17 Lundqvist, L. J. 1988. 'Privatization: Towards a Concept for Comparative Policy Analysis', Journal of Public Policy, 8, 1, 1-19. Mahoney, J. 2000. 'Path Dependence in Historical Sociology', Theory and Society, 29, 4, 507-548. Marques, R. and S. Berg. 2011. ‘Public–Private Partnership Contracts: A Tale of Two Cities with Different Contractual Arrangements’, Public Administration, 89, 4, 1585–1603. Marra A. 2006. 'Mixed Public-Private Enterprises in Europe: Economic Theory and an Empirical Analysis of Italian Water Utilities', Bruges European Economic Research Papers, College of Europe, paper No. 4. Marra, A. 2007. ‘Internal Regulation by Mixed Enterprises: The Case of the Italian Water Sector’, Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 78, 2, 245–75. Massarutto, A. 1993. Economia del ciclo del'acqua. Milan: Franco Angeli. Massarutto, A. 2005. 'La legge Galli alla prova dei fatti: riflessioni su una riforma incompiuta', Economia delle fonti di energia e dell’ambiente, 3, 87-110. McAdam, D., S. Tarrow and C. Tilly. 2001. Dynamics of Contention. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Megginson, W. L. and J. M. Netter. 2001. 'From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on Privatization', Journal of Economic Literature, 39, 2, 321-389. Petretto, A. 2001. 'Processi di riorganizzazione industriale e liberalizzazione dei servizi pubblici locali: problemi e prospettive', Paper n.01/39, Rome: Proaqua. Pettigrew, A. M. 1997. 'What Is a Processual Analysis?', Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13, 4, 337-348. Pierson, P. 2000. 'Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics'. The American Political Science Review, 94, 2, 251-267. Pierson, P. 2004. Politics in Time. History, Institutions, and Social Analysis, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Ragin, C. C. and H. S. Becker. 1992. What is a Case? Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry. Cambridge University Press. Sappington, D. E: M. and J. E. Stiglitz. 1987. 'Privatization, Information, and Incentives', Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 6, 4, 567-579. Schelling, T. C. 1998. 'Social Mechanisms and Social Dynamics', in P. Hedström and R. Swedberg (eds), Social Mechanisms: An Analytic Approach to Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 32-44. Stake, R. E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Starr, P. 1988. 'The Meaning of Privatization', Yale Law & Policy Review, 6, 1, 6-41. Thomas, G. 2011. ‘A Typology for the Case Study in Social Science Following a Review of Definition, Discourse, and Structure’, Qualitative Inquiry, 17, 6, 511-521. Vickers, J. and G. K. Yarrow. 1988. Privatization: An Economic Analysis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Vickers, J., and G. Yarrow. 1991. 'Perspectives on Privatization', Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5, 2, 111-132. 18 Warner, M. E., and G. Bel. 2008. 'Competition or Monopoly? Comparing Privatization of Local Public Services in the US and Spain', Public Administration, 86, 3, 723-735. Weick, K. E. 2001. Making Sense of the Organization. Malden, MA: Blackwell Scientific. Williamson, O. E. 1991. ‘Comparative Economic Organization: The Analysis of Discrete Structural Alternatives’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 2, 269-296. Williamson, O. 1985. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting. New York: The Free Press. Williamson, O. 1975. Markets and Hierarchies. New York: The Free Press. Wollmann, H. 2012. 'Public Services Provision in European Countries from Public/Municipal to Private Sector – and back to municipal?', paper presented at the Symposium on 'Neither Public nor Private: Mixed Forms of Service Delivery around the Globe', University of Barcelona, May 17-18. Wollmann, H. and G. Marcou (2010) (eds), The Provision of Public Services in Europe: Between State, Local Government and Market. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Wollmann, H. 2004. 'Local Government Reforms in Great Britain, Sweden, Germany and France: Between Multi-Function and Single-Purpose Organisations', Local Government Studies, 30, 4, 639665. Wollmann, H. 2000. 'Local government systems: from historic divergence towards convergence? Great Britain, France, and Germany as comparative cases in point', Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 18, 33- 55. Yarrow, G., M. King, J. Mairesse and J. Melitz. 1986. 'Privatization in Theory and Practice', Economic Policy, 1, 2, 323-377. Yin, R. 2003. Case Study Research. Design and methods, 3rd ed. London: Sage. 19 Appendix Interviews: Marisa Abbondanzieri, General Manager OTA “Marche Centro – Ancona” Authority, April 2009. Enrico Asquer, manager ESAF, December 2001. Luciano Baggiani, Chairman Associazione Nazionale Autorità ed Enti d'Ambito, October 2008. Claudio Boldori, General Manager OTA “Cremona” Authority, April 2009. Francesco Bosco, manager ACEA, September 2001. Carlo Casadei, General Manager OTA “Rimini” Authority, April 2009. Stefano Cima, researcher, Istituto Ricerca Sociale, October 2002. Renato Cocchi, member of the Supervising Committee on the Use of Water Resources, October 2002. Diomira Cretti, General Manager OTA “Lodi” Authority, April 2009. Giancarlo Galli, former Christian Democrat MP, former member of the Supervising Committee on the Use of Water Resources, October 2002. Giovanni Gravante, General Manager OTA “Savonese” Authority, April 2009. Renato Drusiani, Chairman Federgasacqua, June 2002. Marco Moselli, General Manager OTA “Bologna” Authority, April 2009. Prof. Gilberto Muraro, Chairman Supervising Committee on the Use of Water Resources, July 2002. Prof. Angelo Nardozza, Chairman OTA “Basilicata” Authority, April 2009. Valter Pallano, manager AMGA, October 2001. Francesco Peri, Manager OTA “Mantova” Authority, April 2009. Paolo Peruzzi, member of the Supervising Committee on the Use of Water Resources, October 2002. Alessandro Piotti, Manager OTA “Lazio 2” Authority, April 2009. Carlo Robutti, General Manager OTA “Piemonte 2” Authority, April 2009. Documents: ASTRID (2008) Infrastrutture e servizi a rete tra regolazione e concorrenza. Le infrastrutture idriche. Rome: Associazione per gli Studi e Ricerche sulal Riforma delle Istituzioni Democratiche e sull'innovazione nelle amministrazioni pubbliche. Rome. CIPE (2002), Risorse idriche. Analisi di settore. Unità Tecnica Finanza di Progetto. Rome. CISPEL Toscana (2001), Rapporto sui servizi pubblici in Toscana. Florence. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (1997-2009), Reports to the Parliament on the State of Water Services. Rome. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2000), Audizione presso la VIII Commissione permanente (Ambiente, territorio e lavori pubblici) Camera dei Deputati. Rome, 12th 20 October. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2000), Audizione presso la XIII Commissione permanente (Ambiente, territorio e lavori pubblici) Senato della Repubblica. Rome, 18th October. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2001), Rapporto sui Piani di Ambito, May. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2001), The State and the Reform of Water Services, Memorandum for the OECD ERP Mission. 25th September. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2001), Audizione presso la VIII Commissione permanente (Ambiente, territorio e lavori pubblici) Camera dei Deputati. Rome, 18 th December. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2002), Incontro con la Conferenza dei Presidenti delle Regioni e delle Province autonome. Rome, 9th January. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2002), Lo stato dei servizi idrici – Secondo rapporto sulle ricognizioni disponibili al 31/12/02, sulle opere di adduzione, distribuzione, fognatura e depurazione, May. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2002), La convenzione tipo del servizio idrico integrato nella legislazione e nella normativa regionale, November. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2003), Lo stato dei servizi idrici: secondo rapporto sulle ricognizioni disponibili al 31/12/2002, sulle opere di adduzione, distribuzione, fognatura e depurazione. Rome, May. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2003), Secondo Rapporto sullo stato di avanzamento della legge 5 gennaio 1994, n.36, July. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2004), II rapporto sui piani d'ambito. Rome, March. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2004), Secondo rapporto sui Piani di Ambito, May. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2004), Terzo Rapporto sullo stato di avanzamento della legge 5 gennaio 1994, n.36, July. Comitato per la vigilanza sull'uso delle risorse idriche (2005), Audizione presso la VIII Commissione permanente (Ambiente, territorio e lavori pubblici) Camera dei Deputati. Rome, 10 th March. Federgasacqua (renamed Federutility since 2005) (1989-2009), Proceedings of the conferences H2Obiettivo 2000, Rome. Proaqua (1995), Struttura della regolamentazione economica in applicazione della legge 36/94. Paper n. 95/01. Proaqua (1995), La remunerazione del capitale investito nel quadro della determinazione delle tariffe idriche: alcune riflessioni. Paper n. 95/02. Proaqua (1996), Efficienza e produttività nel settore idrico. Paper n. 96/03. Proaqua (1996), L'attività di controllo sulla gestione dei servizi idrici. Paper n. 96/05. Proaqua (1997), Studio di fattibilità sull'attuazione della legge 5.1.1994, n. 36. Paper n. 97/11. Proaqua (1998), Servizi idrici tra regolazione e mercato. Paper n. 98/19. 21 Proaqua (1998), La legislazione regionale in materia di servizi idrici. Paper n. 98/22. Proaqua (1999), La legislazione regionale in materia di servizi idrici. Paper n. 99/28. Proaqua (1999), Aspetti economico-finanziari della regolazione dei servizi pubblici locali. Paper n. 99/30. Proaqua (2001), Il finanziamento degli investimenti nel settore idrico. Paper n. 01/37. Proaqua (2001), Processi di riorganizzazione industriale e liberalizzazione dei servizi pubblici locali: problemi e prospettive. Paper no. 01/39. Proaqua (2001), La selezione mediante gara del fornitore di un servizio pubblico locale. Paper n. 01/40. Proaqua (2001), Regolazione e controllo nella convenzione di gestione del servizio idrico integrato. Paper n. 01/43. Utilitatis (2007), Bluebook: I dati sul servizio idrico integrato in Italia. Rome: Utilitatis and ANEA. Utilitatis (2008), Bluebook: I dati sul servizio idrico integrato in Italia. Rome: Utilitatis and ANEA. 22 Tables Firms traded in stock exchange or Safeguarded public owned by financial sector firms institution Regions No. OTAs which have awarded concessions (No. OTAs established) “in house” firms Mixed publicprivate ownership firms Piemonte 6 (6) 17 3 Valle d'Aosta 0 (1) Lombardy 6 (12) 8 1 Veneto 7 (8) 12 Friuli Venezia Giulia 1 (4) 1 Liguria 2 (4) 4 22 (35) 42 (78%) Emilia Romagna 9 (9) 1 Tuscany 6 (6) 1 5 6 Umbria 3 (3) 1 2 3 Marche 4 (5) 3 Lazio 4 (5) 1 Abruzzo 6 (6) 4 Molise 0 (1) Total northern regions Total central regions 4 (7%) 2 11 13 5 6 (11%) 2 (4%) 6 3 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 1 54 10 3 6 1 4 2 6 0 Campania 2 (4) 1 1 Puglia 1 (1) Basilicata 1 (1) 1 Calabria 3 (5) 2 Sicily 5 (9) Total 24 1 8 (22%) Interregional OTAs 4 Total 1 12 (33%) Total southern regions Private firms in negotiated transitory regime 1 32 (35) Sardinia Private firms selected through tender offer competition 7 (19%) 8 (22%) 1 (3%) 0 (0%) 36 2 1 1 1 1 1 4 3 5 1 (1) 1 13 (21) 5 (38%) 2 (15%) 0 1 (8%) 4 (31%) 1 (8%) 13 1 58 14 13 11 5 1 102 0 (1) 67 (92) Table 1. Distribution of the types of firms which were awarded water concessions, per region, 2009 (Source: Supervising Authority on Water Resources and Urban Waste, 2008; web sites of the OTAs, last access in December 2009). 23 Component parts of the water privatization process Initial conditions Inertia part (1994-2001) Alto Valdarno part (1994-1999) Features of the water regulatory governance system (OTA authorities owned and controlled by local governments) Negotiated agreement on reforming water service provision (consolidating water services and opening up access to private operators and investors) Features of the water industry (diffused local government ownership of water service providers) Mixed public-private ownership privatization part (2001-2003) “Formal” privatization part (2003-2006) Features of the water industry (municipal firms) Features of the water industry (diffused local government ownership of water service providers) Stakes of local governments in the water industry Features of the water industry (municipal firms) Stakes of local governments in the water industry Policy content features Policy mandate (consolidating water services, centralizing regulatory functions, opening up access to private operators and investors) Policy mandate (consolidating water services, centralizing regulatory functions, opening up access to private operators and investors) Policy process features Policy statutory procedure (required agreement between local governments) Trajectory of the policy reform Persistence of full public ownership Hypothesized social mechanisms Sequential attention to goals (Cyert and March, Organizational and/or social appropriation 1963) (McAdam et al., 2001) Changed features of the policy content (compulsory tender offer competitions, provisions for mixed ownership firms) Changed features of the policy content (compulsory tender offer competitions, provisions for ‘in house’ firms) Policy feedback (diffusion of ideas) Partial privatization of water services Committed interpretation (Weick, 2001) Table 2. Components of the explanatory argument. 24 Partial privatization of water services ‘Formal’ rather than ‘substantive’ privatization Attribution of opportunities and threats (McAdam et al., 2001) Attribution of opportunities and threats (McAdam et al., 2001) Network diffusion (Hedström and Swedberg, 1998) Actor certification (McAdam et al., 2001)