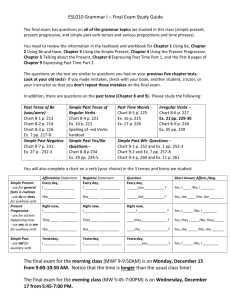

doc - Computing Services

advertisement