Afraid of the Dark Reading Circle Initiative

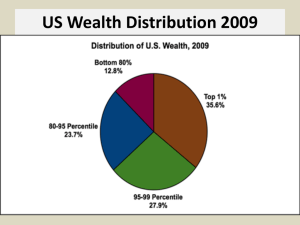

advertisement

Afraid of the Dark: What Whites and Blacks Need to Know About Each Other Dialogue Guide & Workbook Foreword to the Dialogue Guide & Workbook Jim Myers, author of Afraid of the Dark: What Whites and Blacks Need to Know About Each Other Afraid of the Dark was published in April 2000, but little in American race relations or in attitudes about race seems to have changed since then. The issues along the color line that the book describes still exist in the 21st century, reinforced in some cases by new incidents that give credence to old racial attitudes, doubts and fears. Perhaps, America was lulled into thinking that race no longer would be the great divide in American society in the new millennium. Our national government, under Republican dominance, put less emphasis on racial issues. The United States may have had a black secretary of state for the first time. Yet the focus on black-white relations as a national preoccupation seemed further supplanted by a 2003 announcement by the U.S. Census Bureau that Hispanics had become the nation’s largest minority group. Still, in August 2005, the images of thousands of stranded black victims in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina once again put a focus on racial inequities. A black-white perceptual divide, last seen most notably at the time of the 1995 O.J. Simpson trial, clearly re-emerged in polls about the Katrina disaster. When Pew Research Center pollsters asked if the Katrina images “show racial inequality [is] still a major problem,” 71 percent of blacks said, “yes,” race is still a problem, while 56 percent of whites said, “no,” it is not. In a CNN poll, six in ten blacks said the government was slow to react to the Katrina disaster because the stranded victims were black, but only one in eight whites agreed. Meanwhile, prior to the hurricane, an ABC News poll found evidence to claim that positive social contact between blacks and whites was on the rise – even if the rise was relatively small, perhaps even a statistically insignificant change from polls on the subject in the 1990s. The 2005 polls found that 52 percent of Americans said they’ve had a person of another race into their home for dinner. But again there was a racial divide in the answers. Sixtythree percent of blacks said they’d had whites to dinner, while only 48 percent of whites said they’d had blacks to dinner. At the same time, there appeared to be little evidence that blacks and whites were increasingly discussing the doubts and fears that have long arisen along the color lineissues like the overall fairness in society or the negative attitudes that individuals might quietly still harbor. Do blacks and whites discuss sensitive issues like crime or the legacy of slavery in interracial settings? No, rather it seems that social and professional contacts between blacks and whites are predicated on the proposition that difficult issues that divide us will not be discussed. So when I heard about the Reading Circles project undertaken by the Urban League of Greater Kansas City – and that they were using Afraid of the Dark as the means to more penetrating discussions between blacks and whites – I was, of course, thrilled. “It’s helped people bring up the subjects that blacks and white have kept pretty much to themselves,” said Gwen Grant, president of the Urban League of Greater Kansas City. “It’s a great catalyst for dialogue across the color line.” I am convinced that the unease about race will continue unless we address the attitudes and uncertainties that trouble us in more direct discussion. Yet the prospect of talking about such matters is an aspect of race relations about which many Americans are wary, believing such discussions will inevitably be fractious and unpleasant. I’ve also found that this is not the case. Having led or participated in black-white discussions around the country since Afraid of the Dark was published, I’ve seen repeated evidence of goodwill in these discussions – and it comes from both sides of the color line. Yes, we may be wary about what will happen in discussions about race, but many Americans also have a desire to speak sincerely on the subject and hear what others have to say. Many whites want to know what blacks think, and many blacks welcome any indication that whites are listening to what they have to say. Eventually, the interaction between blacks and whites, the give and take, and the sharing of sincere feelings can become a valuable end in itself – not only a key to better relations but as close to a magic fix on race issues as we’re likely to find. Introduction: How We Can Learn from Our Discussions Gwendolyn Grant, president and CEO Urban League of Greater Kansas City and Founder of the Afraid of the Dark Reading Circle Initiative In 2004, one of my white friends, Carol Grimaldi, came by my office to talk to me about this great book she had read along with some members of her predominately white church, Second Presbyterian in Kansas City, and members of a predominately black local church, Blue Hills Church of the Nazarene. This unusual union began in 2002 when members of Second Presbyterian wanted to develop a relationship with a church of color. In the formative stage, a group from the two churches met once a month on Saturdays. After about a year of monthly meetings that involved informal discussions and other assorted activities, they began to wonder what to do next. The monthly activities were okay, but they wanted the time they shared to have more focus. They were contemplating whether they should take on a joint service project when a white member of Second Presbyterian suggested they begin reading Afraid of the Dark. They soon agreed to read the book and meet once each month to discuss their feelings. When Carol first told me about the book, she shared how the group faithfully met once a month for a year and discussed the book chapter by chapter. In her view, this dialogue was the most productive time they shared. Through discussions, they learned more about themselves and each other. Carol said reading the book and talking with blacks about the sensitive issues that blacks and whites don’t talk about together caused her to have an epiphany. She told me that what most opened her eyes was the discussion on slavery and reparations. She said: “As a white American, I’d never thought about the effect of slavery today. Then I wondered why my black friends hadn’t talked to me about this. I remember saying to my group that I wasn’t around 200 years ago, but I have a responsibility to understand. I am sorry it happened, and I am sorry I don’t know more. I want to know more.” One of the blacks in the group had tears in her eyes and said this was the first time in her life that she’d heard a white person say she was sorry about slavery. Carol gave me a copy of the book and told me that I should consider using it as a tool to support the Urban League’s efforts to improve race relations. But honestly, as she was raving about this book and her “epiphany,” I thought to myself, “Yeah, yeah, sure.” Yet I can see how such an experience might cause Carol to have an epiphany. She is someone who has had many interactions with blacks. She is a self-reflective, continuous learner who isn’t afraid to get in the mix with people of color and make a mistake now and then. She is someone who is open and inclusive in her work in the community; she knows how important it is that blacks and Latinos are represented at the table when plans are discussed and decisions are made that will impact them. And finally, she is a white person with a personal commitment to helping her community grapple with tough issues. But knowing Carol as I do, I was skeptical about what impact this Afraid of the Dark book would have on whites who haven’t traveled down the same road as she. After reading the book, however, I was impressed with its simple approach. Most books about race are written from a scholarly, academic framework laced with lots of complex and intricate explanations and theories about why whites and blacks are so divided. Afraid of the Dark defines with such clarity and simplicity so many of the issues that have created this gulf between blacks and whites. It brings to the forefront the stuff that we talk about within our black and white circles, but seldom, if ever across the color line. Because of the book’s straightforward style, it occurred to me that if we could get blacks and whites reading this book together and talking openly with one another, that we might be able to make some movement with the seemingly intractable issue of black/white race relations in America. As a black person, one important lesson I’ve learned about race over the years is that it is non-productive for blacks to “go off” on white people in conversations about race. When blacks “go off” whites back off. They retreat to their comfort zones and inner circles where they talk to one another about how angry, irrational and aggressive blacks are and how they don’t want to be preached to. On the flip side, when whites find themselves in conversations with blacks about race issues, they have to stop behaving like they have to defend or rationalize the actions and behaviors of their forefathers and other whites. When they stop personalizing the issues, then they may not feel like they’re being preached to by blacks who consider themselves merely pointing out the many disparities and inequities they regularly experience, but which appear to go unnoticed by whites. Both blacks and whites should exercise the Golden Rule and treat one another in the same manner that they would want to be treated, and with the same amount of respect, understanding, and patience. It is not rocket science. It really is that simple. But for some reason that is unknown to me, we scoff at the idea in search of some magical or scholarly remedy that will solve America’s color line dilemma. I am not naïve, but I do believe that simple solutions can sometimes be applied to complex problems. About Using the Dialogue Guide & Workbook We have designed the Afraid of the Dark Dialogue Guide & Workbook as a framework in which individuals, pairs, groups, organizations, and entire communities can think and talk about race issues in ways that help them to dig beneath the surface of political correctness to develop authentic relationships between blacks and whites. The Dialogue Guide & Workbook is not intended to serve as the cure-all for everything that is wrong between blacks and whites. It is intended to provoke thinking, ignite dialogue, build new relationships between blacks and whites, and strengthen existing ones. It is designed on the premise that the more blacks and whites interact in positive situations, the higher the likelihood that we will begin to establish more meaningful relationships with each other. Authentic relationships in which blacks and whites see and treat each other as equals will move us closer to achieving an inclusive society that embraces the attributes and contributions of everyone – blacks and whites alike. The Afraid of the Dark Dialogue Guide & Workbook is for people who want to learn, especially while gaining a better understanding of themselves and others. It is for people who want to contribute to the effectiveness of their organizations and create a more inclusive community. In short, the Dialogue Guide & Workbook is for people who want to make a difference. Sample Questions from Chapter One What makes you feel comfortable or uncomfortable talking openly and honestly with whites, Latinos or blacks? What are your reservations? What subjects make you feel uneasy? Describe some experiences you’ve had discussing tough issues with blacks, whites. or Latinos. Sample Questions from Chapter Two How often do you interact with or encounter blacks/whites/Latinos outside of the workplace? What is the nature of these interactions? How do you feel when you’re the only black, Latino or white person (or one of a few) in the room? What do you do? Sample Questions from Chapter Three As a child, what, if anything, did you hear that might have made you think that blacks and/or Latinos are inferior to whites? As an adult, do you see evidence that supports these ideas you heard as a child? If so, please describe. How have your views on race changed over the years? Why? Sample Questions from Chapter Four If more people of another race moved into your neighborhood, would you see this as a “positive” or “negative” change? And why? What would you do—if anything? If you woke up tomorrow and found your neighborhood was suddenly 50 percent black, Latino or white – or 75 percent or 90 percent, how would you feel? Would you be alarmed, mildly worried, or happy? Why? What would you do—if anything? Sample Questions from Chapter Five Where do you get much of your understanding of what blacks, Latinos or whites are like? Do you think what you see on TV or read in the newspaper is an accurate or distorted portrayal of either blacks, Latinos or whites? Do you think positive or negative racial stereotypes appear in any or all of this programming? If so, what are they? Sample Questions from Chapter Six How do you feel about the differences between blacks, Latinos and whites? Should we focus only on what we have in common as the basis for forming relationships? Why or why not? Why do you think the differences between blacks, Latinos and whites are perceived to be negative? Sample Questions from Chapter Seven Can you agree that there could be more than one perspective on American History? What are your thoughts on this? How do you feel when it’s said that America is a nation divided in black and white? Is it true, partially true or without foundation? Sample Questions from Chapter Eight How do you feel about the use of the word nigger? What are your thoughts about the double standard – it’s okay for blacks to use the word and not okay for whites? Without being too offensive, what are the worst things you’ve heard said about blacks , Latinos or whites? Sample Questions from Chapter Nine What is your biggest fear about discussions on the subject of race? Explain. If you’re white, are you ever afraid something you say could cause you to be labeled a racist? Why? Has this ever happened to you? Describe the situation? If you’re black or Latino, are you afraid to speak your mind with whites when talking about race? Why? Are you ever wary that you will be accused of being angry or “having an attitude”? Has this ever happened? Explain. Sample Questions from Chapter Ten What did you learn about slavery in school or college? Do you believe the mere fact that slavery is part of our history perpetuates beliefs that blacks and whites are not inherently equal? Why or why not? Sample Questions from Chapter Eleven Do you believe all men (and women) are equal regardless of their race or ethnicity? Or, do you believe that individuals of different races are more different than they are the same? Explain. What are your thoughts about The Bell Curve theory of intelligence? Sample Questions from Chapter Twelve As a black or Latino person, is there anything about being black or Latino that limits what you can do or achieve in our society? If so, please describe. As a white person, do you have any inkling of what it might feel like to find yourself repeatedly in the minority? Have you had such an experience even briefly? How did you feel and what did you do? Sample Questions from Chapter Thirteen As a black or Latino person, are there things you identify as black culture? What are they? Are you proud of them? Are there other things that are identified as “black” or “Latino” that are embarrassing or that you wish weren’t so? What are they? How has hip-hop culture – rap music, dress styles, flamboyant behavior – influenced your feelings, fears, and perceptions about young blacks and Latinos? Sample Questions from Chapter Fourteen How do you feel about interracial marriage? How would you react to the news that your son or daughter plans to marry someone of another race? Sample Questions from Chapter Fifteen How much of what you think about race comes from watching sports? Explain. It’s said that sports is also an activity in which racial stereotypes are perpetuated. What are your observations? Do you agree, for example, that stereotypes about intelligence or leadership are used, or have been used to limit opportunities for black athletes to play quarterback? Explain. Give some examples to support your point of view. Sample Questions from Chapter Sixteen If it is true that many whites are inexperienced in dealing with black and Latino people, what should Latinos and blacks do – help these whites get a better understanding or let whites live in ignorance? Explain your thoughts. What do you think we need to do to solve the race problem in America? Do you think the problem can be solved? Why or why not? Sample Questions from Chapter Seventeen Why do we reject the notion of the Golden Rule as the best solution to the race problem in America? What solutions do you suggest we apply to bridge the racial divide between blacks, Latinos and whites? Sample Questions from Chapter Eighteen Statistics show that the social and economic gap between blacks, Latinos and whites is narrowing in some areas. Therefore, since some things are getting better, blacks and Latinos should be patient. What are your thoughts about this issue? What ideas do you have for more aggressively narrowing the black/brown-white equality gap? Urban League of Greater Kansas City Afraid of the Dark Dialogue Circle Rules of Engagement 1. Listen actively, respectfully, and sincerely try to understand the other person’s perspective. 2. Speak from your own experience instead of generalizing (“I” instead of “they,” “we,” and “you”). 3. Be honest. Try not to withhold your real thoughts and opinions. 4. Do not be afraid to respectfully challenge one another by asking questions, but refrain from personal attacks – focus on ideas and issues - not personalities and individuals. 5. Participate to the fullest of your ability – community growth depends on the inclusion of every individual. 6. Instead of invalidating somebody else’s story with your own spin on their experience, share your own story and experience. 7. The goal is not to agree – it is about hearing and exploring divergent perspectives. Let’s agree to disagree. The purpose of dialogue is not to reach a consensus, nor to convince each other of different viewpoints. Rather, the purpose of dialogue is to reach higher levels of learning by examining different viewpoints and opinions. 8. The purpose of the dialogue circle is to generate greater understanding about different issues. In expressing viewpoints, try to raise questions and comments in a way that will promote learning, rather than defensiveness and conflict in other circle members. 9. Ask questions and make statements in such a way that will promote greater insight into and awareness of topics as opposed to anger and conflict. Example of a question that may put someone on the defensive: Why do you insist on calling yourself Hispanic? That’s wrong. It seems to me that Latino is the correct term? Can you explain to me why you insist on using the term Hispanic? Example of a non-defensive question: I don’t understand. What is the difference between the terms Hispanic and Latino? 10. Suspend judgment. Try not to jump to conclusions or begin formulating your response while a circle member is speaking. Listen, reflect, and then respond.