Common Grammar Mistakes

advertisement

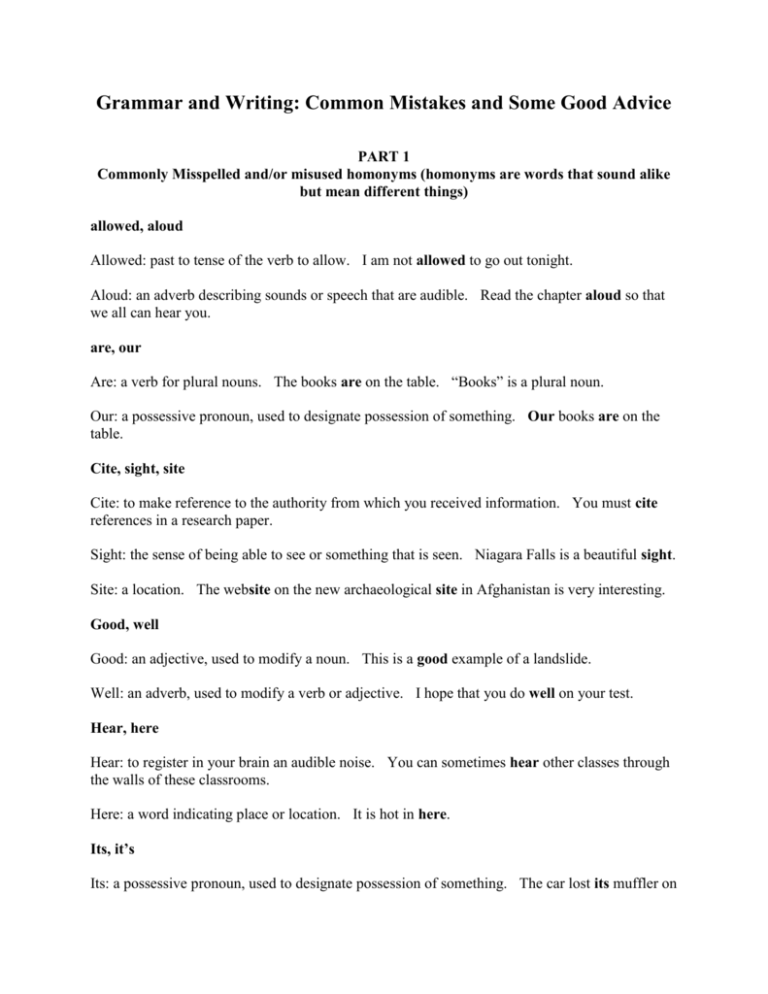

Grammar and Writing: Common Mistakes and Some Good Advice PART 1 Commonly Misspelled and/or misused homonyms (homonyms are words that sound alike but mean different things) allowed, aloud Allowed: past to tense of the verb to allow. I am not allowed to go out tonight. Aloud: an adverb describing sounds or speech that are audible. Read the chapter aloud so that we all can hear you. are, our Are: a verb for plural nouns. The books are on the table. “Books” is a plural noun. Our: a possessive pronoun, used to designate possession of something. Our books are on the table. Cite, sight, site Cite: to make reference to the authority from which you received information. You must cite references in a research paper. Sight: the sense of being able to see or something that is seen. Niagara Falls is a beautiful sight. Site: a location. The website on the new archaeological site in Afghanistan is very interesting. Good, well Good: an adjective, used to modify a noun. This is a good example of a landslide. Well: an adverb, used to modify a verb or adjective. I hope that you do well on your test. Hear, here Hear: to register in your brain an audible noise. You can sometimes hear other classes through the walls of these classrooms. Here: a word indicating place or location. It is hot in here. Its, it’s Its: a possessive pronoun, used to designate possession of something. The car lost its muffler on the way home today. It’s: a contraction of it and is. It’s (it is) too bad that the car lost its muffler. Sweet, suite Sweet: refers to a pleasant taste, smell, or sensation, commonly associated with sugar. Desserts are usually very sweet because the contain a large amount of sugar. Suite: a series of something that goes together or is intimately linked. Families often rent a suite of rooms for long vacations so everyone can have a sense of privacy. their, they’re, there Their: a possessive pronoun, used to designate possession of something. That is their car. They’re: a contraction of they and are. They’re (they are) getting into their car which is over there. There: denotes place or position. The car is over there. There is their car. To, too, two To: a preposition or used with the infinitive form of a verb (to go). I need to go to the store. Too: also, in addition. I need to go to the bank, too. Usually too is preceded by a comma. Two: a whole number, following one and before three. I need to go to the store to purchase two loaves of bread. who’s, whose Who’s: a contraction of who and is. Who’s (who is) going with me? Whose: a possessive pronoun, used to designate possession of something. Whose books are these? -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------PART 2 Commonly misused words and phrases effect, affect Effect: usually a noun, a consequence of something. The effect of good attendance is good grades. *less commonly, used as a verb also, to cause. Dedicated people can effect change on issues that they feel strongly about. Affect: usually a verb, to have an impact in something. Poor attendance will affect your grade. *less commonly, affect can also be used as a noun, a feature that a person adopts to create an image. The vintage clothes she wears are just an affect (sometimes affectation is used instead). This one is a little tough; however, remember that effect is typically a noun and affect is typically a verb. Conscious, conscience Conscious: alert, awake, aware, able to respond to stimuli. It is good to be conscious of your appearance when going to a job interview. It is also good to be conscious during class. Conscience: the little voice in your head that tells you the difference between right and wrong. Many people have white lies on their conscience. Your conscience should tell you that it is not good to miss class. Novel When using the word to refer to a written work, use novel to refer to works of fiction only. A book that is not fiction, like Silent Spring or Walden, is not a novel. Biographies and autobiographies and self-help books are not novels. ONLY fiction books are novels. Take it for “granite” instead of “granted” Granite: an igneous rock type rich in silica and composed of large crystals. The correct phrase is “take it for granted.” -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------PART 3 Common punctuation mistakes Proper punctuation of and, but, or Use of “and,” “but,’ “or” When writing a sentence that has two independent phrases, and should have a common preceding it. An independent phrase is one that can stand alone as a single sentence. Example: I am teaching Earth History, and later in the day I teach Environmental Geology. “I am teaching Earth History” and “Later in the day I teach Environmental Geology” are each stand-alone sentences. When writing a sentence that is composed of a stand alone phrase and a dependent clause (another word for phrase), don’t place a comma before the “and.” Example: I am teaching Earth History and later will teach Environmental Geology. “Later will teach Environmental Geology” is not a sentence. These same rules apply for the use of “but” and “or” to link sentences together. Punctuation of however, therefore, thus, nevertheless, consequently When any of these words is used, as well as some others not listed, they must be preceded by a semicolon and followed by a comma. Example: Textbooks are expensive; however, they enhance learning and are indispensable for some classes. Many students work full time; nevertheless, they excel in their classes. Notice that in these two cases, both phrases connected by the transition word are independent phrases; that is, they can stand alone. If one of the phrases is not independent, then punctuation is similar to that for “and.” Many students are registered for classes at KSU Stark this semester, therefore making class sizes larger. If one of the words is used as an introduction for a sentence, it must be followed by a comma. However, most people are happy that the campus is growing in size. Punctuation of questions At this stage in your academic career, you undoubtedly realize that questions are followed by a question mark instead of a period. However, many students pose rhetorical questions in essays, and end the sentence with a period. When you pose a question, even in an essay, end the phrase with a question mark. How could people have so needlessly polluted the environment? Or, reword so that the phrase is not a question. It is unbelievable how needlessly people polluted the environment. PART 4 Run-on sentences and sentence fragments Many students who are inexperienced writers use run-on sentences and sentences fragments. Run-ons and fragments are problematic because they can make essays and other written assignments very difficult to read and understand. Often a reader will not be able to determine what it was that you meant to say. 1. A run-on sentence is one that is composed of two or more phrases that are not separated by punctuation. In effect, the sentences or phrases run together. I am a student at KSU Stark I am taking four classes this semester. This run-on can be resolved in several ways: I am a student at KSU Stark. I am taking four classes this semester. I am a student at KSU Stark, and I am taking four classes this semester. I am a student at KSU Stark and am taking four classes this semester. I am a student at KSU Stark taking four classes this semester. Notice that each solution requires different punctuation. Why should we care about run-ons? After all, the above five versions all say the same thing. 1. Use of correct grammar and punctuation is expected when writing papers, manuscripts, and memos in a corporate or other job setting. Incorrect use of grammar and punctuation can (perhaps incorrectly, right or wrong) give people the impression that you are uneducated. 2. Some cases are more complicated than the simple one given here. Run-on sentences can be very difficult to decipher by those that are reading your paper (e.g., your professors). 3. Run-ons are often the result of poor proof-reading, which indicates that the writer did not care enough about the assignment to perfect it. Sentence fragments are phrases that are written and punctuated as sentences, but in fact are not complete, stand alone phrases. They lack either a subject or a verb, or they may be a single dependent clause. The book that was placed over on the table. This is not a sentence, because there is not verb that goes with the subject, “book.” When the EPA investigates an area for water pollution. This is not a sentence either, because phrases that begin with “when,” “what,” “who,” or other similar words are dependent clauses. They rely on the rest of the sentence, with a subject and a verb, to make any sense. As this phrase stands, it doesn’t convey a complete thought. What happens when the EPA investigates? The way the sentence is written, we’ll never know. Why should we care about sentence fragments? For the same reasons listed above, fragments are distracting and make written work difficult to read. PART 5 Scientific Punctuation: Common Mistakes and Things People Don’t Know There are a variety of punctuation and grammar rules that only apply to scientific writing. Some of these are actually rules, and some are protocols that are followed by convention. Following these rules and protocols indicates that you are familiar with scientific literature and conventions, thus making your work more credible and professional. Using formal scientific names for organisms. When using the formal genus and species name for an organism, the name must be italicized or underlined to differentiate it from the rest of the text. If it isn’t, it is technically spelled wrong. The formal name for humans is Homo sapiens. Canis lupus is the scientific name for the timber wolf. In the couplet Homo sapiens, Homo is the genus (or generic) name and sapiens is the trivial name. The generic name coupled with the trivial name is the species name. The species name must include the genus. “Sapiens” on its own does not mean anything; trivial names must ALWAYS be coupled with their generic name. Why? Generic names are unique; Homo only applies to a group of hominids with large brains. However, trivial names are not unique; there are many species with the same trivial name. For example, many crabs have the trivial name “granulosa;” the way to distinguish them is by the genus name. Another example is Palaeopinnixa rathbunae, Eriosachila rathbunae, and Zanthopsis rathbunae. All of these are named for Mary Jane Rathbun, a preeminent scholar in the field of crabs, but they are all different species. Generic names can be written without their trivial name, but trivial names are never written without their generic name. You can refer to several species of Homo, but you can’t refer to “sapiens” because by itself it has no meaning. You could be talking about any organism with the trivial name “sapiens.” Only by adding the generic name have you specifically (no pun intended) identified the organism. Within a paragraph, the generic name only needs to be spelled out entirely the first time it is used. After that, you can abbreviate it with its first letter. For example, if you have already used the term Homo sapiens in a paragraph, the next time you use it, you can write H. sapiens. There are only two exceptions. At the beginning of a sentence, spell out the generic name. Never start a sentence with “H. sapiens”. In rarer cases you might be comparing to species that have the same first initial. For example, if you were comparing the mudshrimp Callianassa sayi and Callianopsis clallamensis, you should spell out the generic name. Otherwise, it gets confusing. When you refer to an organism by its scientific name, there is no need to use the word ”the” before it. You would not write, “The Homo sapiens appears to have evolved in Africa,” nor would you write, “The Flexicalymene is an Ordovician fossil.” The species name is like a person’s name. You wouldn’t write “The William Bittle is the dean of this campus.” However, if you are referring to a specific specimen or fossil, use “the,” as in, “The Flexicalymene fossil is very well preserved”.