Source A - Education Scotland

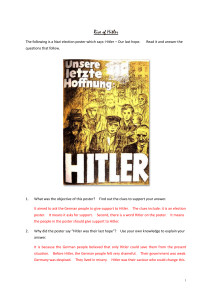

advertisement