European Diploma in Psychology

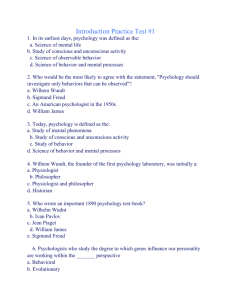

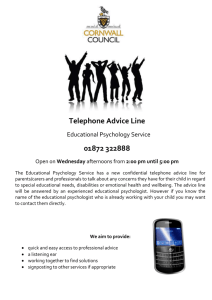

advertisement