Taking Retention to the Next Level - Council for Christian Colleges

advertisement

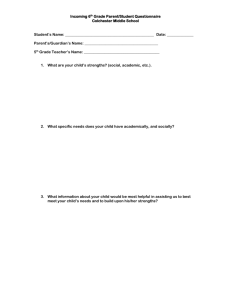

Taking Retention to the Next Level: Of Strengths and Sophomores Laurie A. Schreiner, Ph.D., Associate Dean and Professor of Psychology, Eastern College (PA) While most CCCU institutions have experienced an increase in their retention rates over the past three years, many are not seeing a corresponding increase in our graduation rates. This has led us to take a closer look at when student attrition is occurring. Normally, attrition is highest from the first to second year of college, and attrition rates are typically cut in half each subsequent year. Thus we would expect to see the sophomore-to-junior attrition to be about half of what the first-year-to-sophomore attrition rate was. As an example, if CCCU institutions on the average lose 24% of their students from the first year to the sophomore year, we would expect them to lose about 12% of their students between the sophomore and junior year, then 6% between the junior and senior year, resulting in a graduation rate of about 58%. But the average CCCU graduation rate is only 46.5%. When we look at what is happening in the data, we notice that sophomoreto-junior attrition is much higher than the expected 12% – it is actually 20%, when data are averaged across CCCU institutions. And the higher-than-expected attrition is not the only symptom of the “sophomore slump.” Even for those who remain enrolled, it is not uncommon to see lower levels of motivation, lower grades and a lack of intellectual engagement. In the process of putting together a monograph entitled, Visible Solutions for Invisible Students: Helping Sophomores Succeed, Jerry Pattengale (Indiana Wesleyan University) and I engaged in a number of conversations with sophomores and with higher education professionals who work with sophomores. From these conversations and other research done for the monograph, five factors have emerged as possible contributors to this “sophomore slump:” 1. A decline in institutional attention. The institution which invested so much attention in these students as first-year students now considers them a “success,” and attention shifts to a new crop of incoming students. Over and over we have heard students say that sophomores receive the least amount of institutional attention of any group on campus. Stephanie Juillerat, associate professor of psychology at Azusa Pacific University, uses the analogy of the “middle child syndrome” in her chapter on research with sophomores. Not yet fully into their majors, sophomores do not attract significant attention from faculty. And not yet experienced enough for campus leadership positions, sophomores do not attract significant attention from student development staff. But Juillerat also notes that sophomore expectations are often the highest of any group on campus–especially for advising and for the quality of teaching and service excellence we deliver. We may have done so well with these students in their first year that we have created high expectations for continued attention–at the very time when they are least likely to get it. Thus, in our successful attempt to improve first-tosecond- year retention, we may have simply postponed the attrition to the sophomore year. 2. Entrance into the academic “twilight zone.” A close examination of sophomores’ course schedules reveals that many of them are taking all the general education courses they avoided in their first year and cannot put off any longer. At the same time, they are not fully into a major, have yet to decide on a major, or are taking the major courses which are typically the “weeding out” courses for the major. As a result, their curriculum has intensified in its rigor, but too often is not inherently interesting or motivating to the student. As Chip Anderson, from UCLA and Azusa Pacific University, notes, a lack of “aliveness” can be seen in sophomores when nothing has aroused their curiosity or stimulated their passion. This lack of intellectual engagement then leads naturally to reduced motivation. 3. Waking up to academic reality and not having “Plan B.” It is often in the sophomore year that a student begins to realize that his or her plans to become a physician will probably not materialize if he or she can’t pass Biology. Too often students’ choice of a major reflects their parents’ or peers’ ambitions rather than their own, and waiting much beyond the sophomore year to figure out Plan B is costly. Mike Boivin, from Indiana Wesleyan University, also notes that sophomores are weathering a developmental crisis: the crisis of meaning and purpose. The glow of the first year has faded and students must find some purpose in continuing their college education, and a meaning in life that transcends their parents’ goals for them. When we look at what is happening in the data, we notice that sophomore-tojunior attrition is much higher than the expected 12% - it is actually 20%, when data are averaged across CCCU institutions. 4. “Trading up” to a more prestigious institution. John Gardner, founder of the FirstYear Experience Center, notes that some students enter a Christian college because their parents want them to get a year or two of Christian education before moving on to what they really want to do. He also suggests that a common pattern in students recently is to begin their college education at a less rigorous, less expensive institution, and then transfer into the more costly and prestigious institution from which the student wanted to graduate all along. 5. Not knowing what they want to do with their lives. But perhaps the most common phrase we hear from sophomores who leave Christian colleges is this: “I can’t justify spending this amount of tuition when I don’t know what I’m doing with my life.” Even though college is the ideal place for students to figure out what to do with their lives, too many conclude that they can’t afford to do that when the tuition is so high. This seems to be an ideal point of intervention for Christian colleges in particular. What would happen if we were able to help every student identify his or her talents and strengths and discover what God has called them to do with their lives? Would this not signal an important distinctive of Christian higher education– and one worth the cost? This research with sophomores has led us towards an emphasis on helping students identify their strengths and through that process discover their calling in life. Many national education experts are recommending that students’ academic success should be linked to helping students “come alive to the possibilities of lifelong learning, growth and development” (Anderson & McGuire, 1997, p. vii). In their judgment, the best means of helping students succeed is found in a strengthsbased talent development approach which “advocates that attention and effort be directed toward strengths and to the full development of those strengths. Full development of strengths is the most effective and efficient means of promoting achievement” (pp. vii). -This research with sophomores has led us towards an emphasis on helping students identify their strengths and through that process discover their calling in life. Yet few institutions have embraced this approach in a comprehensive way, partly because higher education has traditionally focused on helping students overcome their deficits (e.g., through remedial programming) as the key to helping students succeed. Recent attention to these remedial programs has shown that most are not achieving their goals of increased student success. In an article entitled “The Consequences of Remedial Education,” Koplik (1999) reflects that, in fact, many of these programs are having the opposite effect of “dumbing down” the intellectual climate of the campus. However, students — even those entering college underprepared — are more likely to be motivated to achieve when their strengths are affirmed and they are encouraged to develop their abilities. Psychologist Claude Steele (1999) refers to this as “wise schooling” and points out that “what doesn’t work is saying, ‘You need remedial work.’ What does work is saying, ‘You may be somewhat behind at this time but you’re a talented person. We’re going to help you advance at an accelerated rate’” (p. 23). He further asserts that this is particularly true for minority students and that the “challenge and the promise of personal fulfillment, not remediation (under whatever guise), should guide the education of these students” (p. 24). So how do we cultivate a campus climate that is strengths-based? In an effort to answer this question, Eastern College (PA) and Greenville College (IL) have collaborated on a FIPSE (Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education) grant to spend the next three years cultivating a strengths-based campus environment. As part of the grant, they will be sponsoring a conference at Eastern College October 26-27, 2001 to report on their results and provide assistance for other institutions wanting to adapt their programs. At least three additional institutions will receive funding from FIPSE to bring a strengths-based approach to their own campuses. Based on the research conducted so far, here are some suggestions for cultivating a strengths-based campus climate: 1. Determine the best way for your institution to identify strengths. There are numerous instruments available, and Eastern and Greenville are each using different ones to determine if the instrument itself makes the difference, or whether it is the program supporting the instrument that is more important. The CCCU has negotiated with three different companies to provide strengths instruments at reduced costs. These three companies are: • The Gallup Organization – their instrument, the Strengths Finder, is an internetbased inventory that identifies five “signature themes” out of a possible 35 strengths. A workbook for students is available and Chip Anderson can conduct workshops on campus to raise awareness of strengths and train faculty and staff to use a strengthsbased approach. Greenville College is using this instrument; for more information contact Dr. Karen Longman, Vice President for Academic Affairs at 618-664-7021 k l o n g m a n @ greenville.edu. • The Career Quest Corporation – their instrument, Career Quest, is Internet-based but can also be obtained as workbooks. There are five inventories that assess personality style, learning style, thinking style, values, and career choices. Each inventory outlines the strengths of the various styles, as well as a potential “shadow side” and ways of communicating and working together effectively. There are workbooks and exercises for students, inventories for faculty and staff, a CD-ROM training program, and consultants available for workshops. Eastern College is using this approach; for more information contact Dr. Laurie Schreiner, Associate Dean: lschrein@eastern.edu or 610-341-5868. • People Management, Inc. – their approach is not instrument-based, but rather is a narrative approach. Each strengths program is carefully customized to meet the needs of a particular campus, and consultants from the company work with faculty and staff in the creation and delivery of the approach. Students are taught to listen to one another’s stories and identify strength themes. Union University is using this approach; for more information contact Dr. Jimmy Davis, Associate Provost, jdavis@uu.edu or 731-6615461. 2. Begin by identifying the strengths of your faculty, staff and administrators. Using the same basic approach that you will use with your students, identify the strengths in your campus personnel as well. Work with them to understand how their teaching, management or work style strengths might enhance their work with students. Greenville College held a campus-wide workshop on strengths, including all faculty, staff and administrators and their spouses. Eastern College held separate workshops for staff and faculty, geared to the interests and needs of each. Whatever method fits your institution, a campuswide emphasis on strengths is a necessary first step toward cultivating this climate. 3. Identify the strengths of all incoming students. Both Eastern and Greenville are using the strengths instruments in their first-year seminar. Modules have been added to the seminar to help students begin a discussion of strengths. All academic advisors have been trained in a strengths-based approach to advising. First-year seminar faculty are the students’ advisors, so there is a natural overlap between the class discussions, the assessment of strengths, and the use of that information in the advising relationship to nurture students’ strengths and capitalize on them as the student makes decisions about course selection, major and career, life goals and activities in which to become involved. 4. Focus on leadership development, calling and the career planning process in the sophomore year. While a strengths-based approach to advising continues with sophomores, here is an increased need for them to understand what a “calling” is–and that a Christian college is a great place to journey toward that calling. Gerald Sittser, from Whitworth College (WA), writes in his recent book The Will of God as a Way of Life, “our calling is inseparable from the journey. In one sense, it is the journey....We discover our calling, not by trying to plan our life out ten years in advance, but by being attentive to what God is doing through immediate circumstances and in the present moment. Over time our sense of calling unfolds simply and, naturally, as scenery unfolds to backpackers hiking their way through the mountains. Rarely will we be able to see the whole pathway stretched out before us at any one time. Sometimes we will only be able to see far enough ahead to keep going” (Sittser, 2000). The advising relationship is one of the primary mechanisms for this discussion with students. It is important to emphasize to students that, with some notable exceptions, most of the time it does not matter what they major in. They will change careers multiple times in life, and many careers they may have later have not been invented yet! A broad preparation in the liberal arts is their best option. Strengths often provide clues to how God is using this student already. Help them understand that knowing who they are is the biggest step toward fulfilling their calling. 5. Provide juniors with a practical application of the strengths-based approach in service learning and cross-cultural settings connected to the major. Research indicates that service learning and cross-cultural experiences that are tied to the major have the greatest impact on students’ identity development (Bussema, 1999). Both Greenville and Eastern have committed to designing service learning courses and/or cross-cultural experiences for juniors in the major that begin with a recognition of the students’ strengths before an assignment to a particular location or experience is made. 6. Provide seniors with a capstone experience that contains a chance to reflect on the development of their strengths and uses their strengths in the selection of internship experiences. Too often, internship experiences are designed for the “typical” student in the major or are based on what is available in the surrounding community. A strengthsbased approach encourages a careful matching of student strengths to internship opportunities and helps the student capitalize on his or her strengths throughout the experience. In addition, there can be senior capstone courses or experiences that can enable a student to write a “strengths autobiography,” or reflect on how the educational experiences of the past four years have cultivated his/her strengths. This not only provides students with an important time for reflection on the meaning of their education, but can also provide valuable insights to the institution about the impact of education on students’ lives. This “strengths initiative” is a new development– within the CCCU and within higher education as a whole. There are very few institutions which have committed to a campus-wide emphasis on strengths-development. This is an opportunity for us as Christian colleges and universities to lead the way in American higher education. The grant awarded to two of our institutions by the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education has enormous potential for funding dissemination efforts not only within the CCCU but beyond. If you are interested in these efforts, contact Dr. Laurie Schreiner or Dr. Karen Longman, project directors, to be placed on our mailing list. And we hope to see you at the conference in October! While a strengths-based approach to advising continues with sophomores, there is an increased need for them to understand what a “calling” is–and that a Christian college is a great place to journey toward that calling.