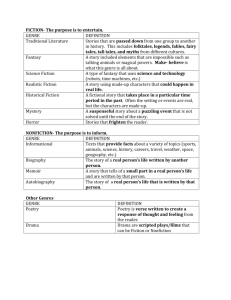

genres

advertisement

TERMS RELATED TO LITERARY STUDIES: GENRES The three KINDS of literature (“kind of literature” means here “műnem”) are: FICTION (epika) POETRY (líra) DRAMA (dráma) Within poetry, fiction and drama alike we talk about GENRES (“műfaj”); so genres are subcategories within the larger categories of fiction, poetry and drama. FICTION (Narrative) fiction (= epika in Hungarian). Please note that “epika” in English is not “epic” [which is the English word for the genre of Homer, “eposz”], neither is it “prose” [“prózanyelv”, that is, a language that does not follow a particular poetic meter, does not rhyme, and is not broken up into lines]) Fiction refers to the fact that these texts are “invented”. Thus, a history book, although it is narrative, does not belong to the category of narrative fiction. Please remember that the English adjectives “fictive” and “fictional” mean “invented” (“kitalált”, “fiktív”) as opposed to “actual”. On the other hand, “fictive” and “fictional” do not mean “fantastic” or “irreal”; Julien Sorel is a fictional character, although he is not fantastic or irreal. KINDS OF FICTION (WITH EXAMPLES) The most frequent error is the mixing up of the basic terms because the Hungarian words here are somewhat misleading. So please remember that a novel means a longer, book-length work of narrative fiction in prose (“regény”) (a novelist is a writer of novels) a novella today means a somewhat shorter, but still quite substantial work of narrative fiction in prose, a short novel or novelette (“kisregény”) a short story is the English for a short work of narrative fiction: “elbeszélés”, “novella” (“novellista” in English is a short story writer) FABLE: a narrative (could be in prose or verse) that teaches a moral lesson. The characters are frequently animals. E.g. the fables of Aesop or La Fontaine (like “The Cricket and the Ant”) FABLIAU (plural: fabliaux): a popular tale in the Middle Ages; makes of women, priests, the clergy in general. They show a striking contrast to legends and romances, their tone is rough and often vulgar. Their aim is to amuse, not to teach. Examples: the Miller’s and the Friar’s Tale in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. ROMANCE (“románcos történet”): in English-language criticism, romance is most often defined as the opposite of the novel (please note that the Hungarian equivalent is not “románc”, which is a kind of love song, as in the poetry of the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca). The novel is usually seen by English critics as a fundamentally realist genre, a genre that attempts to 2 represent the everyday world as we see it. The romance, in contrast, is a fictional narrative genre (in verse or prose) that is not realistic: it is often set in distant times and/or in an ideal world (for instance, medieval chivalric romances that dealt with the heroic deeds and love adventures of knights). Romances tend to present unrealistic, black and white characters: ideally perfect, beautiful and brave heroes and heroines, and demonically evil villains. The plot is often full of unlikely adventures, turns of fate, magical spells, supernatural events and creatures (magicians, dragons, etc); the plot is often structured around a quest: that is, a voyage in search of something (some valuable treasure, a magic object, or a kidnapped heroine). While reading or watching a romance, we suspend our disbelief, our expectations are not based on our everyday experience. In this sense, it is not only fantasy tales (like Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings) that belong to the category of romance, but also texts like Danielle Steele’s prose works, Julia and Harlequin romances, or Latin-American soap operas (or Dallas): in these cases, although the stories do not contain fantastic events, the distance between the represented world and the world of the readers/viewers is almost cosmic. PICARESQUE NOVEL: the earliest type of the novel, appearing in 16th-century Spain. It is a novel about the adventures of a likeable rascal, the picaro. The picaro, the protagonist, who is usually also the narrator, is always on the road, travelling about, serving different masters, having all kinds of odd jobs (some of them not legal) and adventures often both bloody and funny, moving at the periphery of respectable society, trying to be admitted into it. The structure is episodic, the adventures loosely connected through the figure of the picaro. The first picaresque novel was the Spanish text Lazarillo de Tormes (1553), the author of which is unknown (or perhaps Diego Hurtado de Mendoza). Cervantes’s Don Quijote (1605), which is a parody of the chivalric romance, also has a picaresque structure, although the protagonist is not a picaro. The genre was popular in the 18th century: LeSage: Gil Blas (1715); Tobias Smollett: Roderick Random (1748); Daniel Defoe: Moll Flanders (1722). Famous 20th-century examples include Thomas Mann’s Confessions of Felix Krull (Egy szélhámos vallomásai, 1954), Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March (1953), or Umberto Eco’s latest novel called Baudolino (2002). In film, the picaresque genre is represented by road movies (Easy Riders, Natural Born Killers, etc). EPISTOLARY NOVEL (levélregény): a novel written in the form of a series of letters, usually letters written by several characters. The genre was very popular in the 18th century. E.g. Goethe: The Sufferings of Young Werther (1774); Samuel Richardson: Pamela (1740) and Clarissa (1747); Laclos: Les Liaisons Dangereux (“Veszedelmes viszonyok”, 1782); Kármán József: Fanni hagyományai (1796) NOVEL OF MANNERS: a novel that is mainly concerned with the manners of a given society or group of people. Manners is an untranslatable word, referring to the codes of behaviour and contact (contact between individuals and between social classes) in a given society. (The term perhaps could be translated as “etikettregény”.) The tone of such novels is usually comic, in this case they can be referred to as comedies of manners (dramatic works dealing with the same issues are also called comedies of manners). The novel of manners is a typically English fictional genre, given the importance of the highly complex class system and the fascination or even obsession of the English with their class system. Jane Austen’s novels belong to this category (Pride and Prejudice, Emma, etc). The genre is still alive; a late 20th-century representative is Barbara Pym (Jane and Prudence, The Sweet Dove Died, etc) BILDUNGSROMAN (German: “novel of formation/education”). Also called apprenticeship novel: a novel concerned with the development and coming of age of its main character, 3 following his/her story usually from childhood to young adulthood. The genre was very popular in 19th-century fiction. E.g. J.W. F. Goethe: Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (“Wilhelm Meister tanulóévei”, 1795-96); Charlotte Brontëe: Jane Eyre (1847); Charles Dickens: Great Expectations (1861) and David Copperfield (1849-50); Thomas Mann: The Magic Mountain (“A Varázshegy”, 1924) KÜNSTLERROMAN (German: “artist-novel”): a kind of novel that is concerned with the development and coming-of age of an artist (of any kind: painter, writer, musician, etc), from childhood to adulthood, to the moment when the protagonist recognises his/her artistic vocation. Many Bildungsromane are concerned not with the development of the artist but the the problems of being an artist. Famous examples: James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916); Marcel Proust: A la recherche du temps perdu (Az eltűnt idő nyomában, 1913-27); Thomas Mann: Doktor Faustus (1947). Kosztolányi’s Esti Kornél might be considered as an example of the Künstlerroman. HISTORICAL NOVEL: a novel that reconstructs a personage, a series of events, a movement or the spirit of a past age, with special attention to the facts of the age that is recreated. The classic formula of a historical novel is when two cultures are in conflict, one dying and the other being born. Into this cultural conflict, fictional or real personages are introduced who participate in actual historical events. The impact of historical events is experienced by the characters, with the result that a picture of a bygone age is given in personal and immediate terms. (This “classic” formula of the historical novel was laid down by Walter Scott, a nineteenth-century Scottish writer, the first historical novel writer.) Examples: Walter Scott: Waverley; Alexandre Dumas’s works, Leo Tolstoy: War and Peace; Robert Graves: I, Claudius and Claudius, the God. GOTHIC NOVEL: a kind of novel originating in England in the 18th century, and a popular genre ever since. Gothic novels are tales full of mystery and horror; the setting is often a mysterious, medieval castle (frequently haunted), where the heroine goes through all kinds of suffering at the hands of the mysterious villain, until, at the end, she is rescued by the brave hero. Gothic stories use techniques of suspense, frequent themes and motifs include doubles, incest, occultism, ghosts, etc. Early Gothic novels include The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole (1764) and Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). In a more general sense, gothic is used to describe an atmosphere of fear and mystery, for instance in the short stories of the German Romantic writer E.T.A Hoffmann (The Golden Pot – “Az arany virágcserép”, “The Sandman” – “A homokember”), of Edgar Allan Poe in the mid-19th century (“The Fall of the House of Usher”, “The Golden Bug”, etc), or Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1895). A typical popular gothic romance is Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938; the film version was made in 1940 by Alfred Hitchcock, the Hungarian title of both book and film is “A Manderley-ház asszonya”). Gothic fiction is widely used today, for instance in some novels of the British novelist Iris Murdoch (The Unicorn, 1963) or in the novels of the contemporary British writer Patrick McGrath (e.g. The Grotesque, 1989). UTOPIA: not just a fictional genre; it is the description of an ideal, perfect world, set in the future or in some unknown continent or planet. The word “Utopia” was first used in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), but the genre goes back to Plato’s Republic (4th cent. B.C.). Modern utopias include William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890) and H. G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia (1905). A satire on the genre of utopia is Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1874; read backwards: Nowhere) 4 DYSTOPIA (ANTI-UTOPIA): the description of a terrible world, the opposite of utopia. Frequently, dystopias are based on certain negative tendencies in the present and predict a world in which these tendencies will dominate. This is a typically 20th-century genre; its most famous representatives include Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (“Szép új világ”, 1932), George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four (1949), J. G. Ballard’s The Drowned World (1962), and Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange (“Gépnarancs”, 1961). Hungarian dystopias include Karinthy Frigyes: Utazás Faremidóba (1916), Capillaria (1921), Déry Tibor: G. A. úr X-ben (1964). THESIS NOVEL: a novel that deals with some social, economic, political or religious problem in such a way that it suggests a thesis (a statement), usually in the form of a solution to the problem. Different sub-genres of the thesis novel are the sociological novel, the political novel, even the propaganda novel. Examples include Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Charles Dickens’s Hard Times (1854) and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954). NOVEL SEQUENCE (or ROMAN FLEUVE, literally “a river-novel”): a set or series of novels that share common themes, characters or settings, but each novel has its own title. Usually, what is longer than a trilogy (three novels) counts as a novel sequence. The case may be that the same story is continued throughout the volumes, but it may also happen that the parts are linked by a few common characters, situations or central motifs. The novel sequence is a typical product of the 19th century, but examples abound in the 20th century as well. Famous novel sequences are Honoré de Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine (“Emberi színjáték”; a set of nearly 100 books), Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu (“Az eltűnt idő nyomában”, 1908-22) or the English writer Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time (1951-75). INITIATION STORY (beavatási történet): a story (short story, novel, film, drama, etc) in which the protagonist is initiated into some secret or truth about life, about human nature, about sexuality, about himself, about society, etc. In an initiation story, the protagonist starts out in a state of innocence and ends up in a state of experience. (S)he has passed what are called the rites of passage (“az átmenet rítusai”), the necessary difficulties of entering a higher state of knowledge and experience, of becoming an adult. The climax of initiation stories is often a moment of EPIPHANY: originally, epiphany had a religious meaning (the manifestation of God for human beings), but it is generally used to refer to a moment of important revelation, a moment when something extremely important is revealed in a flash about life, death, sexuality, etc. For instance, Katherine Mansfield’s short story “The Garden Party” is epiphanic, the key moment (moment of epiphany) being the young protagonist’s encounter with death. POETRY The Hungarian word líra must be translated as lyrical poetry. Not all texts that are broken up into lines and follow a particular metre belong to the category of lyrical poetry. For instance, Shakespeare’s plays are written in blank verse and yet they belong to the category of dramatic literature. Plays that are written in the form of poetry are called verse plays. Homer’s epics or Pushkin’s Onegin are in verse and yet they are narrative works. Such works that is, narratives written in the form of poetry are called verse narratives. “Verse” may mean poetry, but very rarely. It may also mean a stanza in a poem, but most frequently it refers to a particular formal method of writing poetry, thus we speak about rhymed verse, blank verse or free verse (‘verselés’). (Lyrics means the text of a pop or rock song.) 5 KINDS OF POETRY (WITH EXAMPLES) EPIC (eposz): a genre of narrative verse. A long narrative poem, usually about the deeds of warriors and heroes. Epics have a national significance, embodying the myths, desires and past of a nation on a really grand scale. The hero is an important person, on whose deeds the fate of the nation depends. The importance of the central conflict is indicated by the fact that divine powers (gods, angels etc) are also involved. There is a supernatural machinery, some supernatural forces helping the hero(es) and other powers trying to thwart them (e.g., in the Odyssey, Athene supports and assists Odysseus in his efforts to get home, whereas Poseidon tries to prevent him from arriving back home). Epics have a number of traditional features, generic conventions. Thus, epics open with an invocation to the muse, that is, asking for the muse’s help in completing the task of narrating the epic poem; the beginning of the story is in medias res, that is, we plunge right into the middle of events and the details of what happened earlier are supplied later on. There is usually an enumeration, a lengthy introduction of the opposed forces/armies. Conflicts are usually resolved by means of deus ex machina, that is, divine intervention in the action. Main characters are usually referred to by means of epithets, that is, recurrent adjectives. MOCK-EPIC (mock-heroic epic): a work that makes fun of the traditional, serious epic. It usually works by means of travesty, applying the elevated and earnest language and the traditional features (invocation, enumeration, deus ex machina, supernatural machinery, epithets) of the epic to a trivial subject. The most perfect example of the mock-epic is Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1712-14, “A fürtrablás”), where the main conflict is caused by the cutting off of a lock of the heroine’s hair. The best Hungarian examples are Csokonai’s Dorottya and Petőfi’s A helység kalapácsa. BALLAD: a genre that has features of poetry, narrative fiction and even drama. Ballads usually tell a tragic story (although there are comic ballads, too) in a characteristic way: the beginning is abrupt, much of the story is told through dialogue, the story is told in a fragmented and elliptic way so the reader has to piece it together. The story is dramatic: it is condensed around a few key events, one or two episodes of crisis and climax. Ballads often use refrains and the device of incremental repetition: repeating the same line in a slightly modified way, with the meaning of the line changing between repetitions and becoming more and more dramatic. There are two basic types of ballads: the folk ballad is anonymous, part of the oral tradition, spreading by word of mouth. Folk ballads include “Sir Patrick Spence”, ballads about Robin Hood, or “Kádár Kata”. The literary ballad is composed and written down by poets, imitating the features of folk ballads. Literary ballads include works by Sir Walter Scott, or, in Hungary, the ballads of Arany János (“Tetemrehívás”, “Vörös Rébék”, “A walesi bárdok”, etc). ODE: a lyrical poem with a highly patterned structure, serious in subject matter, earnest in tone. There are two basic kinds of ode. The Pindaric ode (from the name of the Greek poet Pindar) is about a public subject (the fate of the nation, tribute to a famous person, celebration of an event, etc). In contrast, the Horatian ode (from the name of tha Latin poet Horace) is more private and meditative in tone and subject matter. Examples of Pindaric ode include Berzsenyi Dániel’s two odes, both called “A magyarokhoz” or Arany János’s “Széchenyi emlékezete”; Horatian odes include John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” or Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind”. ELEGY: today, an elegy is a lyrical poem in which the speaker mourns for the loss of somebody or something (the death of a friend, the loss of youth or of a better world). Elegies are 6 tranquil poems, often in a pastoral setting, in which the quiet pain over the loss of something specific usually leads to a more general musing about loss and death in general. Famous elegies include Shelley’s “Adonais”, Tennyson’s “In Memoriam” (1850). In Hungarian literature, Janus Pannonius’s “Midőn a táborban megbetegedett”, Berzsenyi’s “A közelítő tél”, or József Attila’s “Elégia”. ECLOGUE: a pastoral poem in the form of a dialogue between shepherds. E.g. Edmund Spenser: The Shepherd’s Calendar (1579); Radnóti Miklós: Eklogák HYMN: a lyrical poem, in elevated style, written in celebration of and addressed to a person or a God or an idea: a god, a saint, a king, an art, etc. E.g. medieval Latin hymns to Mary. Please remember that the English word for “nemzeti himnusz” is not hymn but national anthem. EPIGRAM: a very short poem, usually a witty statement. E.g. Janus Pannonius’s “Egy dunántúli mandulafához”, Kölcsey Ferenc’s “Huszt”. In English poetry, John Donne and Alexander Pope were masters of the epigram. EPISTLE (episztola): a poem in the form of a letter addressed to somebody. E.g. Petőfi Sándor’s epistle to Arany János, or Berzsenyi’s many epistles to other poets and intellectuals (e.g. “Vitkovics Mihályhoz”) HAIKU: a Japanese verse form. It consists of seventeen syllables arranged in three lines of five, seven and five syllables respectively. It is like a miniature snapshot in verse. Its most famous representative was the 17th-century poet called Basho. In the early 20th century, Western poets began to use the principles of haiku (Ezra Pound, Robert Frost, etc) DRAMATIC MONOLOGUE: a genre of poetry; a poem in which a speaker is addressing someone in a certain situation that has to be reconstructed entirely from the speaker’s words. The most famous representative of the genre was the 19th-century English poet Robert Browning (e.g. “My Last Duchess”, “Fra Lippo Lippi”, etc) PATTERN POETRY (képvers): in such poetry, the lines are arranged so that their physical arrangement resembles an object, or suggests a mood or a movement (e.g. Apollinaire: “A megsebzett galamb és a szökőkút”) DRAMA Drama as a kind of literature (mint “műnem”) is drama in English. One particular piece of dramatic art, however, is usually called a play (“színdarab”) the artist who writes plays is called a playwright or a dramatist (“drámaíró). KINDS OF DRAMA (WITH EXAMPLES) MYSTERY PLAY (“misztériumjáték”): medieval plays based on events from the Bible, evolving out of dramatisations of the Latin liturgy and first performed in the churches (usually in times of religious festivals, like Christmas and Easter). From the 14th century, mystery plays moved outside the church, and were performed in long cycles. These cycles represented scenes 7 from the Bible, or the events of the Bible from Creation to the Last Judgment, often lasting several days, each scene played one of the wagons that were going around the cities in a fixed order. Famous English mystery cycles (that is, collection of plays) include the cycles of York and Chester. MIRACLE PLAY (“mirákulum”): medieval religious plays about the lives of saints and the miracles performed by these saints MORALITY PLAY (“moralitás”): medieval plays, appearing later than mystery and miracle plays. Morality plays were allegorical religious dramas in which the forces of Good and Evil (Virtues and Sins) were fighting for and in the human soul. Forces of Good and Evil (Virtues and Sins) were allegorically represented by characters on the stage (e.g the Seven Deadly Sins, Temptation, etc).The action of the plays usually followed the life of a character who represented humanity in general (he was called Mankind, Everyman, Homo, etc): man, born in sin, first indulges in a sinful life but later sees the light of truth and tries to achieve salvation by living a life of virtue. The most famous morality play is called Everyman (ca. 1500). The ending of morality plays is often a danse macabre (French expression; „dance of death”). The danse macabre was also a separate medieval genre in its own right both in painting and literature (and not just drama): the allegorical figure of Death takes people by the hand, inviting them all to dance with Him, in order of age, occupation, social standing. The danse macabre wanted to warn everyone of the nearness of death, and often it emphasised the fact that the rich and the poor, the king and the peasant all become finally equal in death. TRAGEDY: in drama, a tragedy is a play that recounts an important and casually related series of events in the life of a person of significance. The events culminate in a catastrophe and the whole topic is treated with seriousness and dignity. According to Aristotle, the purpose of tragedy is to arouse pity and fear in the audience, and thus clean their soul (“catharsis”). The two key factors that lead to the downfall of the protagonist, according to Aristotle, are hubris (arrogance, pride), that is, a characteristic trait and hamartia (error, tragic deed). These two factors are the sources of the sequence of peripeteia, anagnorisis and pathos (see lecture). We might speak about different sub-genres such as revenge tragedy, heroic tragedy, domestic tragedy (“polgári szomorújáték”). Examples: Shakespeare’s Hamlet or Othello. COMEDY: compared with tragedy, comedy is a lighter form of drama with the primary aim to amuse the audience and which ends happily. Since comedy wants us to smile and laugh, both wit (“szellemesség”) and humour are used. In general, the comic effects may arise from some incongruity of speech, action, situation or character. This incongruity may be verbal (a play on words), bodily or satirical when the comic effect is provided by the fact that the audience is able to perceive a discrepancy between fact and pretence. In contrast to tragedy, where characters are idealised, comedy presents people as human beings with their flaws, limitations and their bodily nature. Thus, comedy is often seen as more realistic that tragedy. Examples: Shakespeare’s As You Like It or A Midsummer-Night’s Dream. FARCE (“bohózat”): a kind of low comedy in which the emphasis is on physicality. Its plot is fast, it uses exaggerated physical action, exaggerated characters, unlikely comic situations, a great deal of slapstick (“börleszk”: comic effects of the most physical type, like falling off ladders and throwing cakes). There are farcical episodes in some of Shakespeare’s plays (Comedy of Errors, The Taming of the Shrew). A famous writer of farces was the French dramatist Feydeau (e.g. A Flea in the Ear, 1907). 8 COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE: a kind of comedy that arose in 16th-century Italy, played by travelling professional actors. The plots were usually based on love intrigues; the plays were only sketchily written, there was a great deal of improvisation, slapstick, pantomime, vulgar humour, and farce. Commedia dell’arte used recurrent types, stock characters, always wearing the same stylised masks and costumes, and spoke in strong dialect. Some of the most famous commedia dell’arte characters are: Arlecchino (Harlequin), a clown figure, a merry, naïve and somewhat awkward servant figure, who acts inconsiderately and therefore runs into all kinds of problems; Brighella, the clever, scheming servant who is usually the driving force of the plot; Pulcinella, the other clownish figure, the unhappy, cuckolded, physically awkward male figure; Pantalone, the rich, greedy, tight-fisted and lecherous old merchant, wearing a long, crooked nose, and red trousers; Capitano, the bragging soldier - miles gloriosus. Commedia dell’arte elements were later used in the plays, for instance, of Moliere, or of Ben Jonson (Volpone, or the Fox, 1606). COMEDY OF HUMOURS: a term applied to the special type of realistic comedy that developed in the 17th century. The comedy derives from characters whose behaviour is controlled by some special whim or humour (itt:“szeszély”). The term goes back to the medieval concept of the human body, when it was thought that one’s mood is determined by the balance of liquids in the body. These liquids were called “humours.” There were four basic liquids: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. The dominance of these liquids determined a character type, so there were sanguinic, phlegmatic, choleric and melancholic characters, corresponding to these liquids. (Thus, “comedy of humours” does not mean a “humorous comedy”.) In a comedy of humours every character is driven by some sort of whim or hobbyhorse, thus the comedy arises out of their narrow-mindedness, eventually. The champion of the comedy of humours was Ben Jonson, his famous plays are Every Man in his Humour (1598) and Volpone or the Fox (1605). PROBLEM PLAY: a problem play is similar to a “thesis novel” in fiction in that it raises a problem, a dilemma (usually of social or ethical nature) and provides an answer for this dilemma. In some sense, Shakespeare’s King Lear is a problem play (a tragedy) and also Measure for Measure (a comedy in form), because they raise an issue that is not satisfactorily solved by the end. More specifically, a problem play is a type of drama evolving in the late 19thcentury that dealt with important social issues like marriage, the situation of women, capitalism, the relationship of money and ethics, etc. Famous examples are Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House or G. B. Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, but such problem plays were also written throughout the twentieth century about various political and social issues. (36)