References - جامعة الملك سعود

advertisement

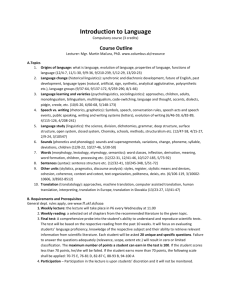

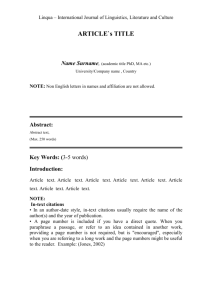

بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم جامعة الملك سعود كلية اللغات و الترجمة قسم اللغات األوروبية و الترجمة برنامج اللغة اإلنجليزية نموذج وصف مقرر دراسي رقم المقرر و رمزه 944 :نجد الوحدات الدراسية المقررة9 : الوحدات الدراسية الفعلية9 : اسم المقرر :المشروع المستوى4 : المتطلب السابق :جميع مقررات المستوى الرابع وصف المقرر: يأتي هذا المقرر بمثابة تتويج للمهارات التي اكتسبها الطالب من خالل دراستهم لكافة مواد الترجمة .يتوقع من الطالب ترجمة مائة صفحة من كتاب إلى في أحد المجاالت التالية: الترجمة العملية ،الترجمة التطبيقية ،نظريات الترجمة ،اللسانيات التطبيقية أو النظرية ،المجال القانوني الديني، التجاري ،السياسي اإلعالمي. متطلبات المقرر: تتم الترجمة من اإلنجليزية إلى العربية بحيث يقدم الطالب عشرة صفحات أسبوعيا ً تتم مناقشتها مع بقية الطالب لالستفادة من سلبيات وإيجابيات الترجمة .يخضع الطالب إلى اختبار نهائي ( ) %04وإلى تقويم مستمر لألداء على مدى الفصل الدراسي (.)%04 التقييم: %60الحضور والمشاركة %53العمل المترجم %9االمتحان الشفهي %04االمتحان النهائي Project in Translation Course Title: Project in Translation Course number: 499 Level: Nine Course Code: Najd Contact Hours: 4 DESCRIPTION: This course crowns the students’ competence in translation activities. Their acquired skills and translation techniques are expected to be displayed through a thorough translation assignment. A book that is relevant to translation theory or translation performance, applied linguistics, theoretical linguistics, law, science, religion, commerce or any related topic of interest to the student translator is assigned. The student is supposed to translate a hundred pages of the chosen book. PROCEDURE: The student is expected to turn in ten pages translated from English into Arabic. Students’ translation is discussed, corrected, and finalized with the participation of other students and the supervision of their tutor. COURSE REQUIREMENT: A translation of a hundred pages from English into Arabic; continuous grading on weekly basis, final exam (40%) and 60% is assigned to the final translation product. EVALUATION: 16% Attendance 35% Final Translation Product 09% Oral Exam 40% Final Exam Guidelines for Papers in Linguistics Estonian Institute of Humanities Department of English Lumme Erilt 1997 Introduction The purpose of these guidelines is to be an aid for the students of Linguistics at the Estonian Institute of Humanities in designing their scholarly papers, i.e. essays, proseminar papers, seminar papers and graduation theses. The guidelines will introduce the main standards generally used by contemporary linguists in documenting their primary and secondary bibliographical sources and give some advice for increasing the general readability of the paper. It should be made clear from the very beginning that there do not exist common documentation standards which apply both to literary scholars and linguists. The former use a standard known as the MLA style, standardised by the Modern Language Association of America. Most publications in humanities and literature use this style. As an introduction to it, see ki. The documentation standard commonly used for English-language publications in linguistics is the so - called LSA style sheet that was devised by the Linguistic Society of America, formerly known also as the Harvard style. This style sheet is somewhat similar to the APA standard (by American Psychological Association), and both are frequently used by social and natural scientists too. Language Use formal English when writing a paper, i.e. avoid colloquialism, slang, jargon and officialese. Do not use any contractions (e.g. I'm, we're, he'd). Be careful not to use sexist language or any other expressions that might be humilating or discriminatory. Avoid excessively long sentences: the average sentence length in English academic writing is 22 words. Prefer a shorter word structure to longer expressions, active speech to passive, verbs to nouns (substantivity). As the syntactic and lexical variety helps to hold readers' attention, avoid boring repetition. At the same time, try to make your text logical and clear and explain everything that is necessary for your reader to follow your argument. Therefore keep the academically minded reader in your mind while you put down your thoughts. Structure To increase the readability of your paper you should structure it properly by presenting your material as explicitly as possible. In the following part certain conventions are introduced. Non-obligatory sections are given in brackets. Title page Estonian Institute of Humanities Department of English TITLE Seminar paper Your name Supervisor: Prof. X Y/ X Y, Assoc. Prof./Lecturer/Asst. Lect. in English Tallinn 2000 (Acknowledgements) If the author wants to thank people who have helped him or her during the work or point out a scholarship or any other stipend used in support, this is usually mentioned here. Sometimes acknowledgements are given under the heading Preface after the summary. (Preface) The Preface is usually used for giving the outline of one's paper, its aims and goals, in the form of a summary of each chapter. For a longer overview of the problems that are discussed in the paper, the section Introduction is used. Contents / Table of Contents Here all the sections of the paper (incl. the Acknowledgements and the Preface, though they precede the Table of Contents) are listed. Page numbers of the section titles are given at the right hand margin of the same line as the titles. Introduction Introduction should present the background knowledge for your paper and help the reader to place your work in the proper context, e.g. a particular field or theory of linguistics. Brief overview of the earlier studies written on your topic might be given, main primary and secondary sources could be listed and the importance and novelty of your research should be brought out. Core chapters This is the main part of your paper, where you should present your research design, material (primary sources), hypotheses, method of the study (e.g. theoretical, empirical, quantitative, qualitative etc.), results and their analysis. Define unfamiliar terms and show their relevance to the theoretical framework you are using. Use tables and figures to illustrate your results, but do not forget to number them and to give clear titles of their informational content. Conclusion Give a general summary of your results and compare them with the results in the secondary sources that you have used. If your findings are different, try to explain why. Refer to your original aims and goals and state whether you could fulfil them. Indicate aspects or areas for further study, but do not use any new information, quotations or examples. References This section lists in alphabetical order of last names of authors all those sources that you have used in the compilation of your paper and referred to in the main body of your text. Sometimes primary sources and secondary sources are listed under separate headings. The works that you have consulted for your study, but have not cited, e.g. dictionaries and encyclopaedias, may be listed under general heading Bibliography or Works Consulted. (Appendices) There might be one Appendix or more, and the purpose of this section is to list long tables, word lists or questionnaires that are referred to in the main text but would be too long or otherwise inappropriate to include as a part of the main body of the text. (Abstract / Summary in Estonian) The Abstract is to give Estonian readers the main idea of your paper. It should contain the aim of your paper, methodology used, most important sources, summary of the analysis and conclusions. Key-words of your paper are also listed. An abstract is necessary in case of longer papers, e.g. your graduation thesis. It need not be bound with the rest of your thesis but may be added as a sheet of (A4) paper. Layout: Volume You will earn 1 credit for every 10 pages for your scholarly papers. Do not prefer quantity to quality, though. Papers that are longer than 25 pages should be presented in folders; others need not be bound. Spacing Use double spacing, to leave space for your supervisor's corrections and comments, except for long quotations - these should be single spaced and indented. Font size Use Times, point size 12 or Courier, point size 11. For headings, Times 14 or Courier 13 may be used. There are two possibilities you can choose from: 1. Use no indentation but leave blank lines between paragraphs. 2. Indent paragraphs about 3-5 spaces, but do not indent the first paragraph of a section or chapter. Be consistent about this throughout your paper. Style Use underlining or italics for emphasis and bold for headings. Linguistic examples should also be italicised. If the examples need translation, this should be given between single quotes, e.g. lingua Lat. `language'. Longer examples should be enumerated and indented, e.g. (1) Alma mater Lat. `university, liter. ``feeding mother''' Double quotes are used only for direct quoting of secondary sources. Margins Leave margins 2-2.5 cm on righthand, top and bottom. Left-hand margin should be 3-4 cm. If possible, justify the right-hand margins. Page numbering Page numbering begins from the title page, but no page number is marked there. All the other pages are numbered in the upper right hand corner of the page. Arabic numerals are used, except for long prefaces, which are numbered with ´´lower case'' Roman. Footnotes and endnotes In the standard used by linguists, bibliographical data is generally not given in footnotes, though sometimes footnotes or endnotes (esp. in case of shorter papers) are used for presenting secondary details. In this case a superscript number is placed in the text, usually after the punctuation mark ending the sentence. No parentheses are used. Headings Major headings are written in capitals, centred and placed at the top of the new page. Sub-headings need not start a new page, but three blank lines should be left before them. One blank line is left after each heading. If the headings are numbered, they are placed at the left-hand margin. No full stop is used after the last digit. References This section lists in alphabetical order of last names of authors all those sources that you have used in the compilation of your paper and referred to in the main body of your text. Sometimes primary sources and secondary sources are listed under separate headings. The works that you have consulted for your study, but have not cited, e.g. dictionaries and encyclopaedias, may be listed under general heading Bibliography or Works Consulted. In-text references In-text references are used in citing the sources that you use in your paper. LSA style in-text references are based on the author-plus-date system, plus page number when necessary. The year of publishing and the number of the page which is referred to are separated with a colon. References are usually given inside a sentence or passage before the full stop. NOTE PUNCTUATION! Reference to the author as a person within the sentence According to Lyons (1981:10), the aim of linguistics is... Itkonen (1991) proposes three different bases for... Tuldava has suggested (personal communication) that... Croft (in press) argues that the solution... Reference to the work itself within the sentence It is clear that both introspective theory oriented `armchair linguistics' (see Fillmore 1992) and... ...the change of language is not seen as a spontaneous transition from one steady state to another `attractor' state as in catastrophe theoretical approaches (cf. Ehala 1996a, 1996b), but... ...the scope of linguistic research has changed its focus from concentrating on minor details to studying language in terms of greater entities (Õim 1989:562). Reference outside the sentence For the diachronic point of view studies implying the correlation between the frequency rank and the ``age'' of vocabulary items provide interesting explanations. (Cf. e.g.Tuldava 1987: 151-164, Piotrovskii et al 1977:57-73) ...have been applied to explain causal determiners of language change. (See e.g. Ritt 1996a, 1996b) Bibliographical references The refernce list should be in the alphabetical order by author's surname. Each entry should be indented five spaces from the second line forward. NOTE punctuation, captalisation and italisation (equivalent to underlining). A book Lyons, John. 1981. Language and linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. A work by more than one author Francis, W. Nelson & Henry Kucera. 1982. Frequency analysis of English usage: lexicon and grammar. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. More than one work by the same author Halliday, M.A.K. 1991a. Corpus studies and probabilistic grammar. English corpus linguistics: Studies in honour of Jan Svartvik, ed. by Karin Aijmer & Bengt Altenberg, 30-43. London, New York: Longman. Halliday, M.A.K. 1991b. Towards probabilistic interpretations. Functional and systemic linguistics: approaches and uses, ed. by Eija Ventola, 39-62. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Halliday M.A.K. 1992. Language as a system and language as instance: The corpus as a theoretical construct. Directions in corpus linguistics: proceedings of Nobel symposium 82, Stockholm, 4-8 August 1991 , ed. by Jan Svartvik, 61-77. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter. An article in a journal or magazine Aristar, Anthony Rodrigues. 1991. On diachronic sources and synchronic pattern: an investigation into the origin of linguistic universals. Language 67: 1-33. An article in a collection of papers Salus, Peter H. 1976. Universal grammar 1000-1850. History of linguistic thought and contemporary linguistics, ed. by Herman Parret. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, 85-101. An article in a collection of papers with more than one editor Hickey, Raymond. 1994. Applications of software in the compilation of corpora. Corpora across the centuries: Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on English Diachronic Corpora, ed. by Merja Kytö, Matti Rissanen & Susan Wright, 165-186. Amsterdam, Atlanta, GA: Rodopi. A collection of papers Hawkins, John A. (ed). 1988. Explaining language universals. Oxford: Basil Blackwell A publication in series Tuldava, Juhan. 1995. Methods in quantitative linguistics. Quantitative linguistics. Vol 54. Trier: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier. A review Wikberg, Kay. 1986. Review of Discourse analysis by Gillian Brown & Georg Yule. Studia Linguistica 40:96-98. A dictionary Longman dictionary of contemporary English. 1978. London: Longman. A work which is not yet published Pintzuk, Susan & Ann Taylor. Forthcoming. Annotating the Helsinki Corpus: The Brooklyn- Geneva-Amsterdam-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English and the Penn- Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Middle English. Doctoral dissertations and Master's Theses Laasberg, Margo. 1997. Events and adverbial modification. Unpublished Master's thesis. Tartu: University of Tartu, Department of Philosophy. A work on CD-ROM Oxford English Dictionary. 1993. CD-ROM. Oxford: Oxford University Press. An on-line source Ritt, Nikolaus. Oct. 4, 1996. Language change as evolution: looking for linguistic `genes'. http://www.univie.ac.at/Anglistik/vinitst.htm An e-mail message Lõhkivi, Endla. 1997, April 7. Re: Muidasjutt. E-mail to Lumme Erilt: lumme@ehi.ee Presentation of primary data Primary data are the text you are analysing, a particular computer corpus or part of it, answers to a questionnaire that you have made up in order to study some phenomenon, audio and video tapes with interviews and the like. Primary data are used first and foremost in descriptive and empirical studies with inductive methodological approach. This means that the study does not look for proofs to a certain theory but tries to make an independent analysis and thereafter draw more or less theoretical conclusions. Do not forget to enumerate your examples and to give an abbreviated source for them. If the same examples are used many times, they need not be written out anew but the number of the example is referred to. Presentation of secondary data Secondary data are the works by other scholars to which you are comparing your ideas and whose earlier results and findings you are using. Secondary sources are referred to in full under bibliographical references at the end of the paper and in short form in the main text (see in-text references above). It is very important to keep your own ideas separate from those of other scholars and make clear distinction where one begins and the other ends. Doing this you can be sure that the readers of your paper cannot blame you for the mistakes and shortcomings of other people and that they can give full credit to your discoveries. At the same time you remain academically honest for not having stolen other people's ideas and for having avoided plagiarism. Therefore use different methods for direct quotations of other linguists' opinions and for paraphrasing their ideas. Note that paraphrasing is preferable and quoting should be used only when it is necessary for terminological purposes or for bringing out something very characteristic and important in the other author's writing. Quotation Short quotations should be included in the main text and put in quotation marks (double quotes). If you omit something, you should indicate that by three dots, and if you add something, you should put it in square brackets, e.g. Halliday (1991b:40) writes that ``in packing up for the move into the twenty-first century we are changing the way knowledge is organised, shifting from a disciplinary discipline towards thematic one[...]''. ...but as an ``interplay between chance and necessity'' (Köhler 1987: 255, emphasis added). Long quotes should be written as block quotations with single spacing and smaller font size. Quotation marks are not used: Halliday (1992:63-64) visualises lexicon as a continuum of words which has two ``ends'': ...at one end are content words, typically very specific in collocation and often of rather low frequency, arranged in taxonomies based on relations like `is a kind of' and `is a part of'; at the other end are function words, of high frequency and unrestricted collocationally, which relate the content words to each other and enable them to be constructed into various types of functional configuration. Paraphrase As mentioned above, it is better to try to paraphrase what the other scholar has written, to say it in your own words. After all, this is a skill that shows your merits too! Too close paraphrase remains plagiarism, so do not be afraid of your `bad English' and try to learn this skill. If you paraphrase a bigger part of the text, it quite naturally takes the form of a short summary. Halliday (1992) stresses the importance of probabilities in choosing one grammatical form rather than another. This means essentially the exclusion of those paradigmatic alternatives within a system that do not hold, the elimination of alternatives with smaller probability. Kõhler (1987:245-146) writes: It is sufficient to find just one single case where a phenomenon diverges from the prediction in order to reject a deterministic law. Most language laws, however, are stochastic. Such laws include in their predictions the deviations which ar e to be expected as a consequence of the stochastic nature of the language mechanisms concerned. Therefore, a stochastic law is rejected if the degree of disagreement between the theoretical ideal and empirical results becomes greater than a certain value , determined by mathematical methods according to a chosen significance level. A paraphrase: Kõhler (1987:245-146) argues that although one single counter-example can be used to show that a deterministic law does not hold, the situation is more difficult with language laws, because the majority of these laws are stochastic rather than determini stic. Thus we can say only with a smaller or greater probability that a certain fact may happen, and a law is rejected if the deviation from the law is greater than a certain mathematically determined value. Cohesion To make your text cohesive and yet not dull, use various verbal connectors in referring to the reported source. Some of them are listed here. ´´Reporting-verbs'' showing your approval Acknowledge, admit, add, confirm, demonstrate, emphasise, formulate, indicate, point out, prove, report, reveal, show. ´´Reporting -verbs'' which leave you room for disagreement Allege, argue, assert, believe, claim, comment, deal with, discuss, examine, find, imply, insist, list, mention, note, observe, postulate, propose, reject, remark, say, state, suggest, survey, write. HELP! When you need instant help with your work: Try this manual; Try jn; Use 'help' command on your word processor; Turn to your supervisor; Turn to a computer consultant :-) References Chesterton1995 Chesterton, Andrew et al. 1995. English department guidelines for essays and assignments... University of Helsinki, Department of English. Johannesson1990 Johannesson, Nils-Lennart. 1990. English language essays: Investigation method and writing strategies. Stockholm University: English Department. Kincaid1996 Kincaid, Arthur. 1996. Writing term papers in literature. Estonian University of Humanities, Department of English. Lund's manual1987 Lund's manual. 1987. How to write a term paper in english. Lund University, Department of English. Unpublished manual. Põldsaar1996 Põldsaar, Raili & Ülle Türk. 1996. Graduation thesis outlines. University of Tartu, Department of English. Tent1995, Feb. 13 Tent, Jan, 1995, Feb. 13. Citing e-texts summary. E-mail in LINGUIST List. About this document ... This document was generated using the LaTeX2HTML translator Version 96.1-h (September 30, 1996) Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, Nikos Drakos, Computer Based Learning Unit, University of Leeds. The command line arguments were: latex2html linguide.tex. The translation was initiated by Lumme Erilt on Thu May 14 17:01:35 EET DST 1998