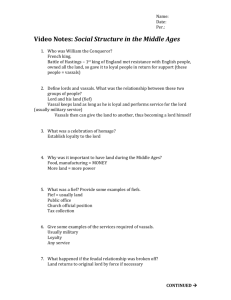

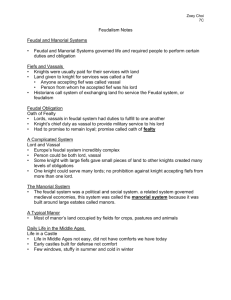

Feudal - Ms. Coates

advertisement

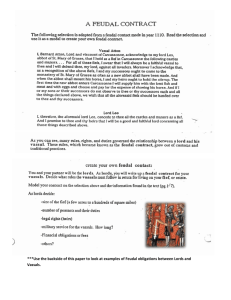

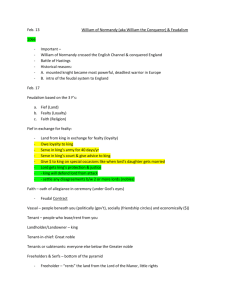

FIEF FAITH FEALTY Your task, both as a small group and in your home-group pairs, is to become experts on your component. The steps below will help guide you through this process. Remember to think both broadly and deeply while being as precise and as specific as you can. Step 1: As a small group (everyone here), clarify what your component means, and brain storm what could be part of it (how your component fits into the Feudal System). Step 2: As a small group, brainstorm a list of good questions that could guide your research into your component. Step 3: Using the questions your group brainstormed, I home-group partners, research the topic. Be sure to consider all the sources available to you. Your notes can be point form, diagrams, charts, drawings…. Any styles that will help you take in, process, and remember the material and will help you teach it to the rest of your group. Step 4: Return to your home-group and teach the other pairs about your component. FEALTY Medieval Sourcebook: "Feudal" Oaths of Fidelity There is increasing uneasiness among scholars about the concept of feudalism as a term to describe non-monetized relationships between the land-holding aristocracy. Still various aspects of lordship and vassalage are documented. Here is are two typical oaths of fidelity.. I: An Anglo Saxon Form of Commendation [from Schmidt: Gesetze der Angelsachsen, p. 404] Thus shall one take the oath of fidelity: By the Lord before whom this sanctuary is holy, I will to N. be true and faithful, and love all which he loves and shun all which he shuns, according to the laws of God and the order of the world. Nor will I ever with will or action, through word or deed, do anything which is unpleasing to him, on condition that he will hold to me as I shall deserve it, and that he will perform everything as it was in our agreement when I submitted myself to him and chose his will. II: Acceptance of an Antrusian, 7th Century [from Roziere: Collection de Formules, No. VIII, Vol I, p. 8] It is right that those who offer to us unbroken fidelity should be protected by our aid. And since such and such a faithful one of ours, by the favor of God, coming here in our palace with his arms, has seen fit to swear trust and fidelity to us in our hand, therefore we decree and command by the present precept that for the future such and such above mentioned be counted with the number of antrustions. And if anyone perchance should presume to kill him, let him know that he will be judged guilty of his wergild of 600 shillings. from E. P. Cheyney, trans, University of Pennsylvania. Dept. of History: Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European history, published for the Dept. of History of the University of Pennsylvania., Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press [1898]. Vol IV, No: 3, 3-5 This text is part of the Internet Medieval Source Book. The Sourcebook is a collection of public domain and copy-permitted texts related to medieval and Byzantine history. (c)Paul Halsall Feb 1996 halsall@murray.fordham.edu Source: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/feud-oath1.html Vassals A Vassal in feudal society was one invested with a fief in return for services to an overlord. Some vassals did not have fiefs and lived at their lord's court as his household knights. Certain vassals who held their fiefs directly from the crown were tenants in chief and formed the most important feudal group, the barons. A fief held by tenants of these tenants in chief was called an arriere-fief, and, when the king summoned the whole feudal host, he was said to summon the ban et arriere-ban. There were female vassals as well; their husbands fulfilled their wives' services. Under the feudal contract, the lord had the duty to provide the fief for his vassal, to protect him, and to do him justice in his court. In return, the lord had the right to demand the services attached to the fief (military, judicial, administrative) and a right to various "incomes" known as feudal incidents. Examples of incidents are relief, a tax paid when a fief was transferred to an heir or alienated by the vassal, and scutage, a tax paid in lieu of military service. Arbitrary arrangements were gradually replaced by a system of fixed dues on occasions limited by custom. The vassal owed fealty to his lord. A breach of this duty was a felony, regarded as so heinous an offense that in England all serious crimes, even those that had nothing to do with feudalism proper, came to be called felonies, since, in a way, they were breaches of the fealty owed to the king as guardian of the public peace and order. The vassals' rights over the fiefs grew larger and larger in course of time, and soon fiefs became hereditary in the sense that investiture could not be withheld from an heir who was willing to do homage. The rules of inheritance tended to safeguard an undivided fief and preferred the eldest among the sons (primogeniture). This principle was far from absolute; under pressure from younger sons, parts of an inheritance might be set apart for them in compensation (appanage;). Vassals also acquired the right to alienate their fiefs, with the proviso, first, of the lord's consent and, later, on payment of a certain tax. Similarly, they obtained the right to subinfeudate, that is, to become lords themselves by granting parts of their fiefs to vassals of their own. If a vassal died without heir or committed a felony, his fief went back to the lord. Source: http://history-world.org/feudalism.htm homage and fealty, in European society, solemn acts of ritual by which a person became a vassal of a lord in feudal society. Homage was essentially the acknowledgment of the bond of tenure that existed between the two. It consisted of the vassal surrendering himself to the lord, symbolized by his kneeling and giving his joined hands to the lord, who clasped them in his own, thus accepting the surrender. Fealty was an oath of fidelity made by the vassal. In it he promised not to harm his lord or to do damage to his property. Although homage had to be rendered directly to the lord, fealty could be given to a bailiff or steward. The lord then performed a symbolic investiture of the new vassal, handing over to him some object representing his fief. The whole procedure was a recognition of both the assistance owed by the tenant to his lord and the protection owed by the lord to the tenant. Source: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/270032/homage FIEF fief, in European feudal society, a vassal’s source of income, held from his lord in exchange for services. The fief constituted the central institution of feudal society (see feudalism). It normally consisted of land to which a number of unfree peasants were attached; the land was supposed to be sufficient to support the vassal and to secure his knight service for the lord. Its size varied greatly, according to the income it could provide. It has been calculated that a fief needed from 15 to 30 peasant families to maintain one knightly household. Fief sizes varied widely, ranging from huge estates and whole provinces to a plot of a few acres. Besides land, dignities and offices and money rents were also given in fief. Source: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/206138/fief Feudalism Feudalism, the prevailing form of political organization in western and central Europe from 900 to 1300. After the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century A.D. it had become increasingly difficult for any government to rule effectively over a large area. Feudalism—a special method of local, rather than central, government—saved Europe from anarchy. Feudal government depended on personal agreements between a number of individuals who possessed military power. These individuals usually had landed estates. They owed loyalty not to a nation, but only to those individuals with whom they had made agreements. The methods by which they received the products of their estates and ruled their workers constitute another aspect of feudalism, called the manorial, or seignorial, system. Many historians believe that the term feudalism cannot be restricted to the government of medieval Europe. Russia, China, the Byzantine Empire, India, and, particularly, Japan had at certain times institutions resembling those of European feudalism. Features of Feudalism Feudal practices varied in different regions of Europe and at different times. The features of feudalism listed below are characteristic of 11th- and 12th-century France, and are considered typical. Lord and Vassal The feudal hierarchy was an arrangement of rank resembling a pyramid. At the top of the pyramid was the king. In the feudal relationship the king was the suzerain, or lord, of a group of dukes and counts who were his vassals. Each of these vassals was in turn lord to lesser vassals, who had even less important vassals. At the bottom of the pyramid were the knights, who had no vassals. Lord and vassal owed certain obligations to each other. The vassal pledged to perform certain services for his lord, and in return the lord granted him a fief, or fee.(The fief was also called a feud, or feod, from which historians derived the term feudalism.) The Fief A fief was anything that was considered useful or valuable. Usually, a fief was a piece of land, jurisdiction over the peasants who lived on the land, and ownership of the goods they produced. All fiefs were technically owned by the king, but a vassal held, in effect, all the rights of ownership of the fief as long as he performed the services required by his lord. (This method of holding another's land is called feudal tenure.) The entire kingdom was divided into fiefs, except for the land held by the king personally. Feudal tenure was hereditary. When a vassal died, his heir did homagefor his fief and swore an oath of fealtyto his lord, promising to be faithful and render service. In the ceremony of investiture, the lord handed his vassal some symbol—such as a sword or a clod of earth—in token of title, and promised to defend the vassal's fief. If a vassal died leaving a minor heir, the lord usually became the guardian of the fief and managed it. If the heir was an unmarried daughter, the lord could select a husband for her because only a male could perform the services of the fief. Feudal Services The services that a vassal owed his lord varied, but the following were common: Military, or Knight, Service. A vassal was expected to serve his lord in war. Usually he served 40 days a year at his own expense if engaged in an offensive action against his lord's enemy. In a defensive action the term of service was unlimited. A knight was expected to furnish only his horse and armor, but great vassals had to supply hundreds of knights and men-at-arms. Court Service. Vassals had to serve, when summoned, in the lord's court. They were called upon to give the lord advice. They also met in assembly to settle disputes between vassals. This was the origin of the principle of trial by a jury of peers, or equals. (Commonly, however, disputes between vassals were settled by combat.) Vassals were also summoned for ceremonial occasions, such as investitures. Financial Obligations. They included: A relief, or gift, to the lord when the fief passed to an heir. It amounted usually to a year's income. Aids, payments made by vassals when their lord needed additional resources. A common aid was to help ransom the lord when he was taken prisoner in war. Other aids were given when the lord's eldest daughter was married and when his eldest son became a knight. Obligation to entertain the lord when he paid a visit. A great lord would sometimes ennoble officials in his household and give them fiefs in return for their services. Among these officials were the sheriff, steward, bailiff, constable, marshal, butler, and chamberlain of a large estate. Their obligations consisted of the fulfillment of their responsibilities as household officials. They enjoyed the same feudal rights as other vassals. This type of tenure was called sergeanty. Feudal Warfare A powerful vassal who did not fulfill his obligations could usually withstand his lord's wrath if he owned a strong castle, since medieval castles were almost impossible to overrun. Forty days' service—the usual limit for knights in the attacking force—left insufficient time for siege operations. Private warfare between nobles who were neither lord nor vassal to each other was common in France, since the king could not control the vassals of his vassals. The church sought to limit strife by forbidding warfare on certain days of the week and during church festivals. Chivalry developed as a code of conduct for knights. The Manorial, Or Seignorial, System The social and economic organization of a fief was based upon the manor, a district held by a feudal lord (seigneur). A manor could be an entire fief or only part. Generally, it included a village and fields, barns, mills, granaries, and sources of water. From the manor's production, a lord derived the resources he needed to support his family and to meet his obligations to his lord. For peasants, the manor provided protection and basic necessities. The non-noble residents of a manor belonged to two main classes, freemanand serf.Various classes of peasants, at different times and in different places, were called villeins.Depending on time and place, a villein's status ranged from that of freeman to that of slave. Freeman. Freemen were tenants of the manor who paid rent, usually in produce. Sometimes they had to perform labor service for the lord. They were free to leave the manor, but while living there were subject to the lord's jurisdiction. Serf. Serfs were semifree peasants who worked a feudal lord's land and paid him certain dues in return for protection and the use of land. They were subject to the lord's jurisdiction at all times. A serf could not be married or leave the manor without the lord's consent. A serf's personal possessions could be taken by the lord as taxes. However, serfs were not slaves and could not be sold. Most peasants in western Europe during the Middle Ages were serfs. The Manorial Economy.The manor was a self-sufficient economic unit. Artisans made essential goods. The land was divided into closed(fenced) and common(shared) lands. Closed Lands consisted of two or three fields, one of which was left fallow in rotating order. The lord's land, called the demesne, was between one-third and one-half of the total. Serfs usually owed from one to three days a week labor on the demesne. The remaining area was divided into many strips and distributed among the serfs so that they could farm it for themselves. In all a typical serf had perhaps 30 acres (12 hectares) of farmland. A certain amount of the serf's crops went to the lord as rent. Common Lands included the meadows, pastures, and forests. The serfs harvested hay from the meadow for the lord's livestock and, in return, were permitted to harvest some for their own use. A similar arrangement existed for the gathering of firewood. If a serf's cow grazed on the pasture, the serf paid a fee to the lord in the form of meat or dairy products. The lord owned all the mills and ovens in the village. Operating a private mill or oven was illegal. Thus, peasants had no choice but to grind their grain in the lord's mills and bake their bread in his ovens. For each of these services, they had to pay a fee in the form of grain or bread. The standard of living on a manor was poor, even for nobles. Castles and manor houses were damp and poorly heated. Peasants lived in flimsy huts with dirt floors and no windows. Diet varied, but if the harvest was bad, the entire manor suffered. Seignorial Jurisdiction The lord was the sole authority over the residents of the manor. He presided over the manorial court, where disputes between serfs were settled and individuals accused of committing crimes were tried. The rank of a feudal lord was reflected in the types of punishments he was permitted to impose; low justicemeant that the lord was limited to ordering punishment for misdemeanors, while high justiceallowed him to order punishment for serious crimes. Lords in France could impose the death penalty. In England, only royal courts could impose this sentence. Source: http://history.howstuffworks.com/european-history/feudalism.htm/printable Common Resources The Feudal System: http://themiddleages.tripod.com/feudal_system.htm FAITH he Catholic Church was the only church in Europe during the Middle Ages, and it had its own laws and large coffers. Church leaders such as bishops and archbishops sat on the king's council and played leading roles in government. Bishops, who were often wealthy and came from noble families, ruled over groups of parishes called "diocese." Parish priests, on the other hand, came from humbler backgrounds and often had little education. The village priest tended to the sick and indigent and, if he was able, taught Latin and the Bible to the youth of the village. As the population of Europe expanded in the twelfth century, the churches that had been built in the Roman style with round-arched roofs became too small. Some of the grand cathedrals, strained to their structural limits by their creators' drive to build higher and larger, collapsed within a century or less of their construction. Monks and Nuns Monasteries in the Middle Ages were based on the rules set down by St. Benedict in the sixth century. The monks became known as Benedictines and took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to their leaders. They were required to perform manual labor and were forbidden to own property, leave the monastery, or become entangled in the concerns of society. Daily tasks were often carried out in silence. Monks and their female counterparts, nuns, who lived in convents, provided for the less-fortunate members of the community. Monasteries and nunneries were safe havens for pilgrims and other travelers. Monks went to the monastery church eight times a day in a routine of worship that involved singing, chanting, and reciting prayers from the divine offices and from the service for Mass. The first office, "Matins," began at 2 A.M. and the next seven followed at regular intervals, culminating in "Vespers" in the evening and "Compline" before the monks retired at night. Between prayers, the monks read or copied religious texts and music. Monks were often well educated and devoted their lives to writing and learning. The Venerable Bede, an English Benedictine monk who was born in the seventh century, wrote histories and books on science and religion. Pilgrimages Pilgrimages were an important part of religious life in the Middle Ages. Many people took journeys to visit holy shrines such as the Church of St. James at Santiago de Compostela in Spain, the Canterbury cathedral in England, and sites in Jerusalem and Rome. Chaucer's Canterbury Tales is a series of stories told by 30 pilgrims as they traveled to Canterbury. Source: http://www.learner.org/interactives/middleages/religion.html Middle Ages Religion Medieval Lives in the Middle Ages as dominated by the Catholic Religion In Europe during the Middle Ages the only recognised religion was Christianity, in the form of the Catholic religion. The lives of the Medieval people of the Middle Ages was dominated by the church. From birth to death, whether you were a peasant, a serf, a noble a lord or a King life was dominated by the church. Various religious institutions became both important, rich and powerful. The lives of many Medieval people were dedicated to to the Catholic church and religion. These are all detailed in the following links all of which relate to Middle Ages Religion. Religion during the Middle Ages The Great Schism Medieval Monks Religious Festivals Medieval Nuns Daily Life of a Monk in the Middle Ages Anchoress Daily Life of a Nun in the Middle Ages Monasticism Medieval Monastery Benedictine Rule Medieval Convent or Nunnery Benedictine Monks Middle Ages Religion - The Christian Religion (Christianity) The Christian religion, or Christianity, is the name given to the system of religious belief and practice which was taught by Jesus Christ in the country of Palestine during the reign of the Roman Emperor Tiberius (42 BC - AD 37). Christianity took its rise in Judaism. Jesus Christ, its founder, and His disciples were all orthodox Jews. The new Christian religion emerged based on the testimony of the Scriptures, as interpreted by the life of Jesus Christ and the teaching of His Apostles, which were documented in the Bible. Middle Ages Religion - The Rise of the Christian Religion (Christianity) in the Roman Era Christianity began among a small number of Jews (about 120, see Acts 1:15). Christianity was seen as a threat to the Roman Empire as Christians refused to worship the Roman gods or the Emperor. This resulted in the persecution of the early Christians, many of whom were killed and thus became martyrs to the Christian religion. The prosecution of adherents to the Christian religion ended during the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine. Emperor Constantine I (AD ca. 285 - AD 337) of the Roman Empire legalised Christianity and Constantine the Great proclaimed himself as an 'Emperor of the Christian people'. Most of the Roman Emperors that came after Constantine were Christians. Christianity then became the official religion of the Roman Empire instead of the old Roman religion that had worshipped many Gods. Middle Ages Religion - The Rise of the Christian Religion (Christianity) in the Dark Ages In the 5th century, the Roman empire began to crumble. Germanic tribes (barbarians) conquered the city of Rome. This event started the period in history referred to as the Dark Ages. The period of the Dark Ages saw the growth in the power of the Christian Church which was then referred to as the Catholic religion. Middle Ages Religion - The Catholic Religion During the Dark Ages and Early Middle Ages the only accepted Christian religion was the Catholic religion. The word Catholic derives from the Middle English word 'catholik' and from the Old French 'catholique' and the Latin word 'catholicus' meaning universal or whole. Early Christians, such as Saint Ignatius of Antioch, who was martyred in c110, used the term 'catholic' to describe the whole Church - the literal meaning being universal or whole. Any other sects were viewed as heretical. The Catholic religion was seen as the true religion. The Christian church was divided geographically between the west (Rome) and the east (Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch). Middle Ages Religion - The Power of the Catholic Church With it's own laws, lands and taxes The Catholic church was a very powerful institution which had its own laws and lands. The Catholic Church also imposed taxes. In addition to collecting taxes, the Church also accepted gifts of all kinds from individuals who wanted special favors or wanted to be certain of a place in heaven. The power of the Catholic Church grew with its wealth. The Catholic Church was then able to influence the kings and rulers of Europe. Opposition to the Catholic Church would result in excommunication. This meant that the person who was excommunicated could not attend any church services, receive the sacraments and would go straight to hell when they died. Middle Ages Roman Catholic Religion - The Great Schism and the Great Western Schism In 1054 there was a split between the Eastern and Western Christian Churches prompted by arguments over the crusades. This split was called the Great Schism. The Great Western Schism occurred in in Western Christendom from 1378 - 1417. This was caused by an Italian pope called Pope Urban IV being elected and establishing the papal court in Rome. The French disagreed with this and elected a French Pope who was based in Avignon. The schism in western Christendom was finally healed at the Council of Constance and the Catholic religion was referred to as the Roman Catholic Religion. Source: http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/middle-ages-religion.htm