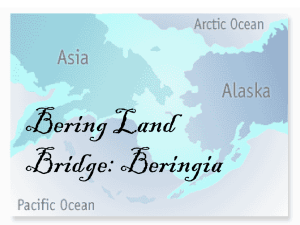

Beringia Land Bridge..

advertisement

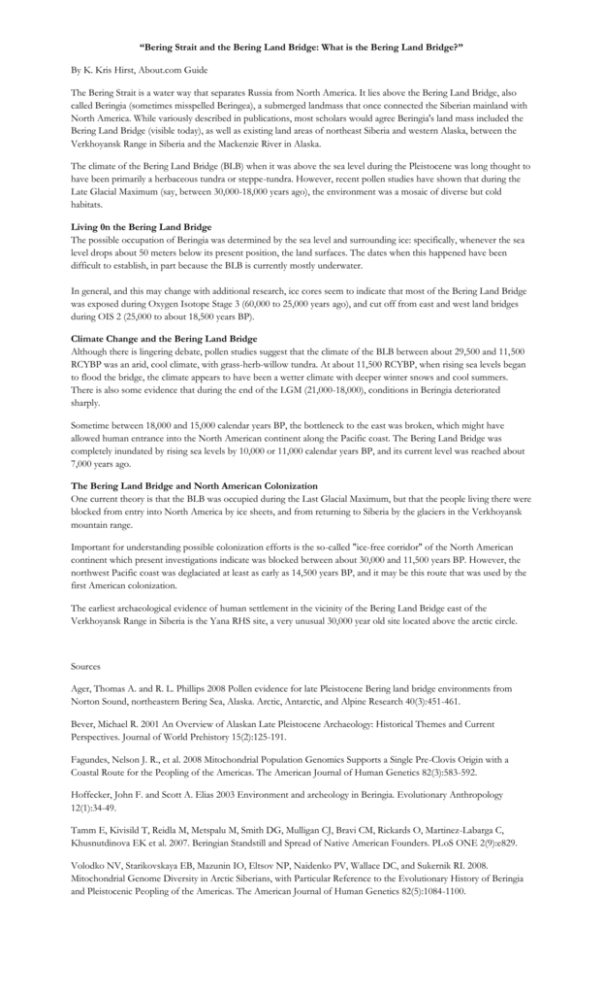

“Bering Strait and the Bering Land Bridge: What is the Bering Land Bridge?” By K. Kris Hirst, About.com Guide The Bering Strait is a water way that separates Russia from North America. It lies above the Bering Land Bridge, also called Beringia (sometimes misspelled Beringea), a submerged landmass that once connected the Siberian mainland with North America. While variously described in publications, most scholars would agree Beringia's land mass included the Bering Land Bridge (visible today), as well as existing land areas of northeast Siberia and western Alaska, between the Verkhoyansk Range in Siberia and the Mackenzie River in Alaska. The climate of the Bering Land Bridge (BLB) when it was above the sea level during the Pleistocene was long thought to have been primarily a herbaceous tundra or steppe-tundra. However, recent pollen studies have shown that during the Late Glacial Maximum (say, between 30,000-18,000 years ago), the environment was a mosaic of diverse but cold habitats. Living 0n the Bering Land Bridge The possible occupation of Beringia was determined by the sea level and surrounding ice: specifically, whenever the sea level drops about 50 meters below its present position, the land surfaces. The dates when this happened have been difficult to establish, in part because the BLB is currently mostly underwater. In general, and this may change with additional research, ice cores seem to indicate that most of the Bering Land Bridge was exposed during Oxygen Isotope Stage 3 (60,000 to 25,000 years ago), and cut off from east and west land bridges during OIS 2 (25,000 to about 18,500 years BP). Climate Change and the Bering Land Bridge Although there is lingering debate, pollen studies suggest that the climate of the BLB between about 29,500 and 11,500 RCYBP was an arid, cool climate, with grass-herb-willow tundra. At about 11,500 RCYBP, when rising sea levels began to flood the bridge, the climate appears to have been a wetter climate with deeper winter snows and cool summers. There is also some evidence that during the end of the LGM (21,000-18,000), conditions in Beringia deteriorated sharply. Sometime between 18,000 and 15,000 calendar years BP, the bottleneck to the east was broken, which might have allowed human entrance into the North American continent along the Pacific coast. The Bering Land Bridge was completely inundated by rising sea levels by 10,000 or 11,000 calendar years BP, and its current level was reached about 7,000 years ago. The Bering Land Bridge and North American Colonization One current theory is that the BLB was occupied during the Last Glacial Maximum, but that the people living there were blocked from entry into North America by ice sheets, and from returning to Siberia by the glaciers in the Verkhoyansk mountain range. Important for understanding possible colonization efforts is the so-called "ice-free corridor" of the North American continent which present investigations indicate was blocked between about 30,000 and 11,500 years BP. However, the northwest Pacific coast was deglaciated at least as early as 14,500 years BP, and it may be this route that was used by the first American colonization. The earliest archaeological evidence of human settlement in the vicinity of the Bering Land Bridge east of the Verkhoyansk Range in Siberia is the Yana RHS site, a very unusual 30,000 year old site located above the arctic circle. Sources Ager, Thomas A. and R. L. Phillips 2008 Pollen evidence for late Pleistocene Bering land bridge environments from Norton Sound, northeastern Bering Sea, Alaska. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 40(3):451-461. Bever, Michael R. 2001 An Overview of Alaskan Late Pleistocene Archaeology: Historical Themes and Current Perspectives. Journal of World Prehistory 15(2):125-191. Fagundes, Nelson J. R., et al. 2008 Mitochondrial Population Genomics Supports a Single Pre-Clovis Origin with a Coastal Route for the Peopling of the Americas. The American Journal of Human Genetics 82(3):583-592. Hoffecker, John F. and Scott A. Elias 2003 Environment and archeology in Beringia. Evolutionary Anthropology 12(1):34-49. Tamm E, Kivisild T, Reidla M, Metspalu M, Smith DG, Mulligan CJ, Bravi CM, Rickards O, Martinez-Labarga C, Khusnutdinova EK et al. 2007. Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders. PLoS ONE 2(9):e829. Volodko NV, Starikovskaya EB, Mazunin IO, Eltsov NP, Naidenko PV, Wallace DC, and Sukernik RI. 2008. Mitochondrial Genome Diversity in Arctic Siberians, with Particular Reference to the Evolutionary History of Beringia and Pleistocenic Peopling of the Americas. The American Journal of Human Genetics 82(5):1084-1100.