giovanni corbellini

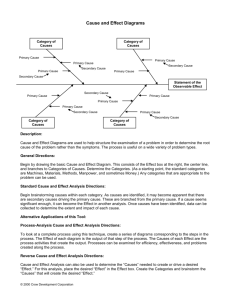

advertisement

giovanni corbellini diagram “Kazuyo Sejima is a new type of architect… If there is one way that best describes the spirit of her structures, it would be to say that it is ‘diagram architecture’”. With this short definition Toyo Ito, in addition to precisely describing the synthetic quality of the works of his colleague, introduces a more general question, attributing to the diagrammatic substance of her architecture a specific role of newness in the evolution of the discipline. We may agree more or less with this interpretation, but it is certain that the diagram has played an increasingly central role in the most advanced architectural production. In recent years it has become a specific feature of the neo-avant-gardes. Hyungmin Pai retraces this development in American architecture, revealing the progressive obsolescence of systems of representation from the beaux-arts tradition, focused on the object in itself, as opposed to more effective graphic instruments. Instruments capable of synthetically relating strictly compositional aspects to those of function, symbolism, concept, time and, definitively, to all those elements that cannot be probed by means of simple projective geometry, yet represent a major part of contemporary design scenarios. There is little doubt, in fact, that the present architectural situation is marked by the progressive, accelerated burst of questions, information, needs and intentions that are increasingly diversified and heterogeneous with respect to the specifics of the discipline. The efficacy of the diagram lies to a great extent precisely in its interdisciplinary potential, its capacity to act as a mediator between different, inter-related quantities, helping to explain them and providing a sort of graphic shortcut for the representation of more or less complex phenomena (for a collection of diagrams from a wide range of areas, see Fisuras, July 2002). So it is no surprise that its appearance in the field of architecture is often linked to incursions of personalities from other backgrounds, often so effective that they leave lasting signs. Besides the well-known example of Bentham’s panopticon, reinterpreted by Foucault and then Deleuze as a paradigm of social control, we can also site the “diagram only” indications on the drawings used by Ebenezer Howard to promote his idea of the garden city. The undeniable communicative power of these graphics, connected to the correspondence between concepts and their representation, is accompanied by the fact that diagrams can take the form of true “machines for thinking”: the mathematicians Gerard Allwein and John Barwise reveal the extreme elasticity of these tools, capable of being simultaneously precise and imprecise, of simplifying and illustrating complex phenomena, eliminating the superfluous. Critical attention began to focus on these themes between the end of the second world war and the 1970s. This involved the spheres of architectural and urban design, as well as that of historical interpretation. The bubble diagrams produced at Harvard under the guidance of Walter Gropius (Herdeg, 1983) were joined by the research of Christopher Alexander (who considers the diagrams to be the most significant contribution of his very well-known Notes on the Synthesis of Form), the essays of Kevin Lynch (from The Image of the City to The View from the Road – in collaboration with Appleyard and Myer – developing new graphic tools for the Ito, Toyo, “Diagram architecture,” El Croquis, no 77, 1996. Pai, Hyungmin, The Portfolio and the Diagram: Architecture, Discourse, and Modernity in America, MIT Press, 2002. Soriano, Federico (ed), Fisuras, July 2002, Diagramas @. Foucault, Michel, Surveiller et punir, Gallimard, 1975, eng. tr. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Allen Lane,1977. Deleuze, Gilles, Foucault, Editions de Minuit, 1986, eng. tr. Athlone, 1988. Allwein, Gerard and John Barwise (eds), Logical Reasoning with Diagrams, Oxford University Press, 1996. Herdeg, Klaus, The Decorated Diagram: Harvard Architecture & Failure of the Bauhaus Legacy, MIT Press, 1983. Alexander, Christopher, Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Harvard description, respectively, of perception of urban space and the interaction between space and speed), the comparative analysis of the villas of Palladio and Le Corbusier proposed by Colin Rowe and that of the proportions of Renaissance buildings by Rudolf Wittkower, as well as the contributions of Lawrence Halprin on creative processes, of Robert Venturi (who in Learning from Las Vegas utilizes diagrams both to describe and compare urban phenomena and to effectively illustrate his theoretical conclusions), and many others. The interval of historicist postmodernism, with architecture’s retreat into its most traditional specificities, temporarily overshadowed most of this research, especially the more explicitly anti-tectonic approaches that began to spread in the 1980s, making an early appearance in the exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture (MoMA, 1988, with projects by Gehry, Libeskind, Koolhaas, Eisenman, Hadid, Coop Himmelblau and the Villette by Tschumi). The competition for the Parc de la Villette (1982) represents again a fundamental turning point for the subsequent development of architecture, also in this specific area of the diagram. Both Tschumi and, above all, Koolhaas demonstrated on that occasion (and in many other projects) that the diagram is the tool that allows control of complex, innovative design processes, progressively freed of objectives of a formal character, and capable of producing works of architecture that come to strategic grips with uncertainty and indeterminacy. From this moment on, the diagram has entered a new period of research that has only recently begun to generate critical fallout. In 1998, the Dutch magazine Oase devoted a theme issue to Diagrams, followed that same year by ANY no 23, whose contributions defined the main themes of research on the potential of the diagram as a simultaneously reducing and proliferating, abstract and open machine. The issue was edited by Ben van Berkel and Caroline Bos, confirming the interest of the UN Studio in diagrams, as demonstrated in other forays on this theme, from Mobile Forces to the chapter “Diagrams” in Move, where they emphasize the tool’s capacity to deal with complexity. Nevertheless, the goal of gathering all the infinite varieties of information involved in design processes makes the reading of their diagrams equally if not more difficult than the interpretation of the objects produced, whose relationship with the diagrams appears to be more evocative than directly explanatory or generative. The year 1999 was one of particular critical intensity for the subject of the diagram. Bart Lootsma presented, in “A+U”, some works by Ben van Berkel, underlining the iconic quality of the graphic representations, which were able to sum up innovative processes for shared use by extended design teams. Thomas Kamps proposed a systems approach to interpretation of the diagram, from analysis to project to communication. Peter Eisenman and Stan Allen, two of the authors of ANY no 23, demonstrated their belief in the central importance of this tool by also returning to the subject in their monographs. In Eisenman’s case, the approach is entirely within architectural composition, seen as an abstract exercise of three-dimensional configuration of space. The diagram enters his research as an analytical-cognitive tool, applied first to the study of the architecture of Terragni, and then evolves into a design tool capable of describing and implementing the various University Press, 1964. Lynch, Kevin, The Image of the City, MIT Press, 1960. Appleyard, Donald, Kevin Lynch and John R. Myer, The View from the Road, MIT Press, 1964. Rowe, Colin, “The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa,” Architectural Review, 1947. Wittkower, Rudolf, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, Warburg Institute, University of London, 1949. Halprin, Lawrence, The RSVP Cycles: Creative Processes in the Human Environment, Braziller, 1970. Venturi, Robert, Denise ScottBrown and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas, MIT Press, 1972. Johnson, Philip and Mark Wigley (eds), Deconstructivist Architecture, MoMA, 1988. Bijlsma, Like, Wouter Deen, Udo Garritzman (eds), Oase, no 48, 1998, Diagrams. Van Berkel, Ben and Caroline Bos (eds), ANY, no 23, 1998, Diagram Work. Van Berkel, Ben, Mobile Forces, edited by Kristin Feireiss, Ernst & Sohn, 1994. Van Berkel, Ben and Caroline Bos, Move, UN Studio & Goose Press, 1999. Lootsma, Bart, “Diagram in costumes,” A+U, no 342, 1999. Kamps, Thomas, Diagram Design: A Constructive Theory, Springer, 1999. Eisenman, Peter, Diagram Diaries, Thames & Hudson, 1999. Allen, Stan, Points + Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City, Princeton Architectural Press, 1999. successions of compositional transformations behind his proposals (decomposition, grafting, scaling, rotation, inversion, superposition, drifting, folding...). The “grammatical” efficacy of Eisenman’s theoretical construct also seems to stimulate Stan Allen, but with a closer connection to the concrete reality of contemporary contexts. Instead of abstract morphological operators, his approach is based on tactics of management of the fluid variability of situations, putting the accent on potential dynamics instead of rigid rules. Both volumes contain essays by Robert E. Somol, who also contributed a fundamental article to ANY no 23, and represents the expert of reference on this issue. “Urbanism without Architecture” lets Somol extend the discussion from the work of Allen to comparison with the neo-avant-gardes of the 1990s, while “Dummy Text, or the Diagrammatic Basis of Contemporary Architecture”, in its approach to the complex theoretical and design construction of Peter Eisenman, covers historical precedents, parallels with other arts, critical analysis and interdisciplinary references (from film editing to the linguistics of Chomsky, the Cubism revisited by Rowe and Slutzky to the nouveaux philosophes...), and puts the accent, in the end, on the progressive function of diagrammatic design, as opposed to the strategy of designing with diagrams. A strong connection between products and the methods of their ideation that Anthony Vidler, in “Diagrams of Utopia”, also recognizes in the most radical examples of research aimed at testing the limits of architectural action. POST SCRIPTUM A concise review of ANY no 23 is in: Corbellini, Giovanni, “Attraverso qualcosa di scritto,” Parametro, no 252-253, 2004, ANY 1993-2000: Una antologia. An analysis of the debate around diagrams at the end of the century: Lootsma, Bart, The Diagram Debate or the Schizoid Architect, in Marie-Ange Brayer and Béatrice Simonot (eds), Archilab’s Futurehouses: Radical Experiments in Living Space, Thames & Hudson, 2002. mobile On drawing as a thinking tool: Laseau, Paul, Graphic Thinking for Architects and Designers, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1980. And specifically about diagrams: Albarn, Keith and Jenny Miall Smith, Diagram: The instrument of thought, Thames & Hudson, 1977. Glasgow, Janice, Hari Narayanan and Bolakrishnan Chandrasekaran (eds), Diagrammatic Reasoning: Cognitive and Computational Perspectives, AAAI Press, 1995. A collection of graphic solutions: Abe, Kazuo and Fumihiko Nishioka (eds), Diagram graphics: The best in graphs, charts, maps and technical illustration, Pie Books, 1992. A reference author for visual communication: Tufte, Edward R., Visual explanations: Images and quantities, evidence and narrative, Graphics Press, 1997. Tufte, Edward R., The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, Graphics Press, 1983. Some other contribution by Gilles Deleuze about diagrams: Deleuze Gilles, Le Pli: Leibniz et le baroque, Editions de Minuit, 1988, eng. tr. The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, Athlone Press, 1993. Deleuze, Gilles, Francis Bacon: Logique de la sensation, La Différence, 1981, eng. tr. Francis Bacon: the Logic of Sensation, Continuum, 2003. Eisenman, Peter, Giuseppe Terragni: Transformations, Decompositions, Critiques, Monacelli Press, 2003. Rowe, Colin and Robert Slutzky, “Transparency. Literal and Phenomenal, Part I,” Perspecta, no 8, 1963. Rowe, Colin and Robert Slutzky, “Transparency. Literal and Phenomenal, Part II,” Perspecta, no 13-14, 1971. Vidler, Anthony, Diagrams of Utopia, in Catherine De Zegher and Mark Wigley (eds), The Activist Drawing: Retracing Situationist Architectures from Constant’s New Babylon to Beyond, MIT Press, 1999. Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari, Capitalisme et Schizophrénie, tome 2, Mille Plateaux, Editions de Minuit, 1980, eng. tr. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, University of Minnesota Press, 1988. Deleuze, Gilles, Différence et répétition, Presses universitaires de France, 1968, eng. tr. Difference and repetition, Athlone Press, 1994. An interesting teaching experience: Angélil, Marc, Inchoate: An Experiment in Architectural Education, Eth/Actar, 2003. On diagrammatic automatism by MVRDV and the production of “datascapes”: MVRDV, Farmax: Excursions on Density, 010 Publishers, 1998. The diagrammatic abstraction is the core of Soriano’s book: Soriano, Fedrico, Sin_tesis, Gustavo Gili, 2004. Design machines, devices and other tools: Corbellini, Giovanni (ed), Parametro, no 260, 2005, Progetti automatici. A polemic position against diagrams: Aureli, Pier Vittorio, Gabriele Mastrigli, “Architecture after the Diagram,” Lotus, no 127, 2006. And my “users’ guide”: Corbellini, Giovanni, “Diagrams: Instruction for Use,” Lotus, no 127, 2006.