Technology Cluster Strategy 2009

advertisement

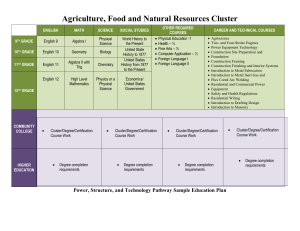

Los Alamos National Laboratory Technology Cluster Strategy Northern New Mexico Regional Economic Development Initiative Bennett Collier, Andy Gunter, Jacqueline Shen, Peter Zullo Summer 2009 Table of Contents Executive Summary....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Recommendations ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Branding ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Networking............................................................................................................................................ 4 Government .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Overarching ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Characterization of the Technology Cluster ................................................................................................. 5 S.W.O.T. Analysis .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Value Chain Analysis ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Cluster Competitors and Their Success Factors ............................................................................................ 8 Suggestions for Future Study ...................................................................................................................... 14 Acknowledgements..................................................................................................................................... 15 Works Cited ................................................................................................................................................. 16 Appendix A: Past Studies & Reports ........................................................................................................... 18 Appendix B: A Case Study of Research Triangle Park ................................................................................. 18 Appendix C: Full List of Considered Tactics................................................................................................. 20 Branding .............................................................................................................................................. 20 Networking.......................................................................................................................................... 20 Government ........................................................................................................................................ 20 Executive Summary Three strategies for developing Northern New Mexico’s economy beyond its government base were synthesized. These strategies and the tactics within them are products of publicly-held meetings with the private sector. By following the recommendations set forth, a stronger technology cluster in the region will arise, creating jobs, wealth, and economic diversity. The overarching recommendation for the Technology Cluster is to identify a private sector group or organization to implement the branding, networking and government recommendations, thereby creating both central leadership and a driving force for the cluster. Through meetings following completion of the Technology Cluster Strategy, REDI has identified the Northern New Mexico Chapter of the New Mexico Technology Council (NMTC) as the Technology Cluster leader and implementer. REDI and NMTC have developed a scope of work for NMTC to implement the branding and networking recommendations in 2010 and 2011, pending funding from REDI, and as described in the Technology Action Plan at the end of this document. Government recommendations will be considered in future years, and may be implemented by NMTC, if the organization develops policy and advocacy capabilities within the next one to two years. Introduction The Northern New Mexico Regional Economic Development Initiative (REDI) is one of Los Alamos country’s Progress through Partnering initiatives, funded by increased gross receipts tax revenue from the change in Los Alamos National Laboratory’s (LANL) contractor status, and is cooperated with the counties of Los Alamos, Rio Arriba, Santa Fe, and Taos (Northern New Mexico). REDI developed a regional economic development strategic plan in February 2009 which involved a four-cluster industry development approach. The following report is focused on strategies and action steps involved with the technology cluster strategy, and was prepared by a group of 2009 summer MBA interns at LANL’s Technology Transfer division. The team involved with the project held a series of three public meetings to solicit research and ideas on how to develop the technology cluster in Northern New Mexico. In parallel, an evaluation of the technology cluster’s seven segments against a competitive framework was conducted. The seven segments of the cluster as defined by the REDI report were Energy & Environment, Aerospace, Bioscience/Life Sciences, Imaging/Detection, Nanotechnology, Optics/Photonics, New Media, and Information Technology. Each segment was treated as a cluster for the purposes of evaluation and comparison to analogues using Harvard Business School’s Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness Cluster Profiles project (HBS: Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, 2008). Recommendations The following tactical recommendations are grouped under three categories of strategies, alongside an overarching strategy. These strategies are laid out in order of priority in addition to the tactics under them. Although the creation of all possible strategies and tactics was a result of MBA-conducted secondary and primary research, the following list represents the items which were voted on by the private sector and are representative of that voice’s opinion. Branding Brand NNM as a place of a culture of innovation. Anchor this claim behind the national laboratories and strategically leverage Albuquerque as a proximal asset for travel, capital, and academic resources by way of the Rail Runner o There is work underway to suggest that a technology conference be held in Northern New Mexico in 2010, with a branding effort done in parallel. This initiative may not pursue the goals of long-term branding and multidimensional marketing channel approach, which is what is suggested here. Seek out motivated, independently-minded entrepreneurs of the “Young Professional” demographic and try to lure them to the region by highlighting NNM’s natural strengths o There seems to be no existing initiatives around this tactic currently Create a web-video (YouTube subscription channel with periodic updates of new videos) & TV video campaign highlighting NNM as technology hub o Although a YouTube video is for Southern New Mexico is publicly available for tourism (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cW5Aijyos4), NNM should establish a subscription channel for technology marketing which would be periodically updated with a new focus of its technology competency. Networking Harmonize the Northern New Mexico professional networks into one communication medium o Santa Fe Business Network (LinkedIn group) has a broad, unilateral reach to individuals in NNM and may serve as a “meta” layer over the other organizations. Consortium of business leaders who can work with local colleges to help them understand graduate needs in future, and can get programs to meet those needs o There exist conferences in New Mexico which try to attract academic participants in addition to private industry attendees, however the conferences do not communicate the needs of the industry to academia in a direct, accountable fashion. Target the Young Professional demographic to NNM networking events, via free food and spirits, in order to invigorate the attendee presence and bring in fresh ideas o New Mexico Technology Council (NMTC) hosts a regular “Beer and Gear” event, but the topics of such meetings may solely attract young professionals. The successful elements of the Beer and Gear event, alcohol and interesting topics, should be designed into existing organizational meetings to lure an additional, new audience. Government Extend the tax relief offered by New Mexico Partnership, for a select group of industries, to a broader group. The current ‘High Wage Jobs’ tax credit offers incentives for businesses adding skilled employees, but it does not offer incentive to hire lower-wage support-staff (whose wages may still be above-median depending on the region). o For more information on current tax-credits, and where there may be gaps in the taxincentive code, see: http://www.nmpartnership.com/WhyNM_Incentives_GeneralTaxCredits.aspx Develop a repository of completed grant work within the state (grants funded by the state for research, those funded by in-state universities, or those funded by the federal government and completed in New Mexico). Make the repository available as a ‘knowledge source’ for university researchers and students to access. Sponsor lab-space in local universities and research institutions for students and professors to pursue further advancements of the grants’ scientific results. As a model, the National Science Foundation recently awarded University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill money to fund a similar effort. Information may be found at: http://uncnews.unc.edu/content/view/2537/138/ Establish more grants that give would-be entrepreneurs money to pursue a business project. o Several members of the NNM business community expressed concern at the lack of funding available (as grants, loans, or small equity investments) to develop their businesses after they have run through initial funds from sources such as LANL’s VAF awards. Their concern is that if their ventures are perceived as ‘too risky’ by venture capitalists or earlier-stage angel investors, they will run out of funding to develop prototypes, initiate manufacturing, or undertake other critical business functions. Overarching Establish follow-up of REDI implementation which a private firm-composed panel o The New Mexico Technology Council has a Board of Directors populated with leaders in academia, the private sector, and the public sector. The NMTC organization would be an excellent driver of this report’s tactics and would ensure the follow-through of the recommendations put forth. Characterization of the Technology Cluster The construct used to evaluate the competitiveness of the technology cluster in Northern New Mexico is Michael Porter’s Determinants of Cluster Competitiveness Diamond. The diamond framework characterizes aspects of the cluster into five interrelated groups: Input Conditions, Related and Supporting Industries, Demand Conditions, Context for Strategy and Rivalry, and Other. Porter used this device to steer a meta-study of clusters throughout the world. The insights gained from the study are crucial to establishing a sustainable technology cluster in New Mexico. One such insight is that a cluster which solely relies on Input Conditions is doomed to be an uncompetitive player. Instead, a balance effort to strengthen all the diamond edges with an emphasis on Input Conditions as the first priority will lead to a competitive cluster in the global field (van der Linde, 2003). The same template used in the meta-study was employed for every segment of the technology cluster in NNM to determine the state of the cluster’s competitiveness. Because the segments were had a nominal population of firms in each of them, gathering detailed information about each segment proved to be challenging. However once each of the seven templates was populated, scores were averaged across the segments to give a broad overview of the technology cluster as a whole. The result was that the technology cluster was rather weak (Porter’s label) and was not changing for the better or worse. Although the five groups were in the correct proportions of strength, each group needed to be amplified to have a significant contribution to the competitiveness of the cluster. S.W.O.T. Analysis Strengths: Cultural diversity Arts & Culture (Native American, Opera, Spanish market) Climate and Outdoors World renowned institutes (SFI, LANL, INFOMESA) Local orgs supporting econ. dev (RDC, SMDC, SFEDI) Tourism economic base Many private schools Ample government employment Favorable tax and regulatory environment relative to some other major states (e.g. CA) Large population of people with second hones and retirees Publicly available high performance computing (NMCAC) Weaknesses: Weak primary & secondary public education Poor marketing link in value chain Low number of successful LANL spin-offs Socio-political climate discourages explosive business growth Some infrastructure issues Lack of affordable housing Workforce quality Population is sparse and isolated from rest of NM Opportunities: Supporting Arts & Culture Industry Collaboration of governments at many different levels (county, city, region) Foster pueblo cooperative projects Attract film industry Leverage research capabilities of local institutes Attract the businesses and talent leaving problematic states (e.g. CA) Right-sizing business growth to gain socio-political buy-in Education 2.0 around technology, products, and services (e.g. remote education) Threats: Water sustainability Elected officials support recruitment rather than entrepreneurship Roads Weak telecommunication infrastructure Ample government employment competes for skills, talent, and ambitions Declining federal budget at LANL 20+ years to fruition Value Chain Analysis As documented in the Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan (REDSP), prepared by the Regional Development Corporation in February of 2009, 156 companies in the technology, new media/IT, and energy/green business clusters have been identified in the Northern New Mexico region. Of these, 51 were identified as technology companies. The authors used the categorization from this report to create Figure 1 showing the distribution of these companies throughout the value chain. (a) (b) Figure 1 –Value chain distribution of companies identified in the Northern New Mexico Region. Chart (a) shows the distribution of companies in the technology, new media/IT, and energy/green business clusters. Chart (b) shows the distribution of companies identified as part of the technology cluster. Of the 156 companies identified, 75 were categorized as R&D companies, 25 were categorized as production, integration, or manufacturing companies, and 41 were categorized as retail companies. Within the 51 companies of the technology subset, 32 were categorized as R&D companies, 11were categorized as production, integration, or manufacturing companies, and 7 were categorized as wholesale and distribution companies. In both groups, a heavy regional focus on research and development can be observed, understandable based on the world class research facilities that exist in the area. Past the R&D majority, it is interesting to note that there is a lack of companies at the prototyping and marketing points in the value chain and a relatively small numbers of companies at the Export/Wholesale point. The significant absence of firms involved with marketing/distribution and design/prototyping presents a potential problem for the success of the cluster. Although these two pieces of the value chain may be outsourced to different geographies or contracted on a virtual basis, the R&D leadership of the region will inevitably suffer if great ideas lose momentum on the “last mile” of the value delivery process. Moreover, a stable, virtual chain link can only be installed in the NNM value chain if well developed and mature links exist before and after the virtualized link. The nature of technology firms in this area is both nascent and myopic (for good reason at such a stage in a business’ evolution process), suggesting a dynamic marketing or prototyping chain link is unlikely to be successful. A challenge cited in the REDSP is a lack of management firms in the area that can assist entrepreneurs in growing their business, based on only a small number of firms in the area that specialize in this area. The report recommends attraction and creation of such companies, as well as improvement of the connections between existing management companies and entrepreneurs. It is also noted that management companies focused on the New Media segment of the Media cluster are present and could potentially be engaged to aid growth of a tech cluster. Another challenge identified in the REDSP is the understanding of the value chain that is present in the area. R&D firms can potentially focus on manufacturing of their inventions, whether or not they have the requisite skills and expertise to do so. The report cites a need for better information for entrepreneurs about how to get their technology to market, including options such as sale of the technology or acquisition of the firm itself. It then goes on to recommend strategic recommendations based on the limited manufacturing capabilities of the area, suggestions to explore development of prototyping firms in the Espanola/Pojoaque valley, and potential partnerships with other regions with strong manufacturing capabilities. Cluster Competitors and Their Success Factors Because the term “technology cluster” can encompass many different specialties, the seven segments defined in the REDI plan were used as a basis for comparing against other global clusters. Those segments are Aerospace, Bioscience/Life Sciences, Imaging/Detection, Nanotech, Optics/Photonics, New Media, and Information Technology. (1) Aerospace – Seattle Region Seattle’s aerospace cluster dates to 1910, when Washington native William Boeing moved to the city with the intention of starting an airplane business (Seattle: History, 2006). Six years later his seaplane completed its first successful flight, and Boeing’s dream became reality. Boeing became something much larger over the decades than even its founder could have imagined. Of the four or five major aerospace companies that drove the industry’s growth in the twentieth century, all are now part of Boeing. Experts estimate that for each person Boeing hires, an additional two jobs are created elsewhere in the region to support that growth (NWA Spotlight). These suppliers, however, as well as government officials, do not sit idly by expecting Boeing’s growth to keep the region’s aerospace cluster strong. Instead, a coalition of government-sponsored groups from Snohomish County and Seattle, and the region’s Aerospace Trade Association, began formulating aerospace cluster initiatives earlier this decade (Aerospace Cluster Initiatives). The outcome of their efforts was an action plan, developed in 2005, assigning responsibilities for five initiatives to local government and business coalitions. Key Takeaways: 1. The cluster’s creation was partly luck, but focused efforts to keep Seattle an aerospace center have resulted in continued growth in the area’s high-tech job market. 2. Local Boeing suppliers did not wait for the government to take the lead; they created a consortium of small- and medium-sized businesses to champion their cause. 3. Together with government, local aerospace businesses launched a ‘Workforce Development Initiative’ to ensure ready access to skilled labor for companies, thereby reinforcing their choice to stay in the Seattle area. RTP Case Study Involvement of enthusiastic visionaries from government, business, and academia was key to RTP’s initial success. Leaders rallied public support by tapping sense of ‘pride’ in the region, and used very few tax dollars for the effort. The project’s success required perseverance over more than two decades before RTP ‘took off.’ Each initiative included key milestones and steps to get there, as well as key persons responsible for achieving those milestones. Each initiative’s objective was clearly defined to better its chances of success. Key takeaways applicable to the Northern New Mexico Project: The aerospace industry has evolved into one where a few end-producers rely on hundreds of suppliers, each of which usually specializes in just a few components of the overall plane or spacecraft. In Seattle this model works because of Boeing’s presence. But in Northern New Mexico, the very few aerospace companies that exist are unlikely to coalesce into a unified cluster without the presence of a larger company closer to the final production stage. The presence of Los Alamos National Laboratory increases the chances, however, that aerospacefocused lab spin-off companies may thrive in Northern New Mexico. While its inventions are not all available to the public, the lab still stands as a center for aerospace innovation with, for example, its Space Data Systems group. Rather than by attempting to lure aerospace companies to the region, Northern New Mexico is likely to see success in this sub-cluster another way. Its best opportunity is to nurture a small, but diverse and growing group of aerospace start-ups in the region while they build contacts in Albuquerque, Seattle, and other cities with a greater aerospace presence. (2) Biosciences/Life Sciences – Greater Denver Region Greater Denver is home to approximately 11,700 biosciences-related jobs across two major subsectors, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology. At its heart are major research institutions such as UC-Denver’s Health Sciences Center, the National Jewish Medical Research Center, and several others. But even though huge research institutions, and companies of similar size such as Amgen, Roche, and Medtronic, are all central to the cluster, an amazing 2/3 of all companies in the cluster employ less than 10 people (Development Research Partners, Inc., 2005). These firms benefit from favorable tax policies and access to funding for R&D from no fewer than five specialized venture capital firms. The area is also home to two bioscience-specific business incubators. Finally, the former Fitzsimmons Army Medical Center is now undergoing a renovation that will transform a state-of-the-art 227 acre campus, which will have enough room to both foster start-ups, and allow for anchor tenants to develop. Key Takeaways: The MetroDenver Economic Development Corporation actively touts these advantages via a sixpage brochure outlining statistics, regional growth both within biosciences and within the general economy, and the upcoming developments that may persuade businesses to relocate or start from that region. Marketing materials take care to emphasize the high quality-of-life measurements consistently applied to the region based on outdoor lifestyles and cleanliness. According to a 2004 study by the Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy, Colorado ranks second in the U.S. Economic Freedom Index, meaning its businesses face low regulatory hurdles slowing down their success and growth. (3) Imaging & Detection – Cleveland, OH The biomedical imaging technology cluster has been growing for a number of years. The Ohio state government has been instrumental in providing funding to universities, research institutions, and the private sector to collaborate and foster relationships in research and development to commercialization. In 2008, the government awarded $143 million to 10 projects for this purpose, with $24.9 million awarded to several collaborations between schools and other partners in the Northeast for bio-medical imaging development (Soder, 2008). A number of large and small medical imaging manufacturers with operational plants in Cleveland and Northeastern Ohio also contribute to the growth of the imaging and detection technology cluster, specifically for medical applications. Note: The Imaging & Detection proto-cluster in Northern New Mexico spans a number of applications in a wide variety of industries. According to the extended REDI report, companies listed under this subcluster include: Jemez Technology, Taos Techsonics, Tektronics, EcoSensors, Elemectric, Hytec, Southwest Sciences, Sparks Mechanical, and Star Cryoelectroncics. These companies operate in security, operations manufacturing, medical imaging, and optical & radiographic imaging systems, to name a few industries. Given the broad nature of this sub-cluster and low number of data points with which to draw conclusions, it is challenging to find a successful parallel sub-cluster in another region truly comparable to that in Northern New Mexico. Key Takeaways: Government funding dedicated to researchers at universities, research institutions, and the private sector is a major factor that influences the potential success of a cluster. Industry production and involvement in development is key to fueling the growth of a cluster. (4) Nanotechnology – Arizona (statewide) In the 1990’s, the Arizona state government began investing millions of dollars for R&D in nanotechnology. As interest in nanotechnology grew, involvement from the private sector continued the development and commercialization of institute is to advance innovations for improving human health and quality of life through use-inspired, biosystems research and effective, multidisciplinary partnerships. AzBio currently contains eight centers with a significant effort focused on nanoscale biosystems and devices, including the Centers for Applied NanoBioscience, Single Molecule Biophysics, and Bio-Optical Nanotechnologies. Combining the 301 initiative and ASU’s commitment, the Arizona Biodesign Institute’s total investment over the next five years is estimated to be $200 million ($140 million for two new buildings) and approaching $500 million over 10 years. Approximately $100 million of this is specifically coupled to nanotechnologies. More information on AzBio can be found at http://www.azbio.org/. Additional investments in specific nanotechnology products. In January 2003, theactivities include Proposition 301 Materials/Nanotechnologies seed funding and equipment matches at approximately $0.5 million per year for shared user fabrication and characterization facilities at ASU (the Center for Solid State Electronics Research (NanoFab, 2003) and the Center for Solid State Science (LeRoy Eyring Center for Solid State Science, 2008), and upcoming seed investments in nanoelectronics and in sensing (Murdock, Crosby, Stein, & Swami, 2003). Additionally, The Arizona Nanotechnology Cluster, an Arizona not-for-profit organization, was formed to share and promote technological advances in the fast-growing field of nanotechnology. The organization’s membership includes an active group of interested engineers (electrical, mechanical and chemical), scientists (medical and materials) and businesspeople from both industry and academia. Arizona’s strength in semiconductors positions the state for research and development in nanoelectronics and photonics. A number of partnerships between large companies such as Mitsubishi Corporation, Materials and Electrochemical Research Corporation, and Research Corporation Technologies fuel the momentum behind commercializing such materials through joint ventures. Arizona’s research universities also contribute to the Nanotechnology Cluster. Arizona State University’s Nanostructures Research Group and three departments within the newly established Biodesign Institute and the University of Arizona’s Advanced Microsystems Laboratory and Microelectronics Design and Test Laboratory are among the state’s world class research institutions with focus in nanoelectronics and photonics. Additionally, a number of successful nanoelectronic startups have been spun out of Arizona’s technology transfer endeavors, in part encouraged by discipline-specific entrepreneurship education courses, such as “Entrepreneurship for Engineers” at the University of Arizona (Arizona Nanotechnology Cluster, 2009). Key takeaways: Trade organizations that facilitate active communication and collaboration between engineers, scientists, and business people from industry and academia impact the success of the cluster. Large corporations continue to fuel the momentum behind commercialization. However, if attracting large corporations will negatively compete against smaller home-grown companies in Northern New Mexico, encouraging technology transfer programs at the Lab and through the universities has proven very successful as well. Providing access to state-of-the-art facilities for investigators from the universities, state agencies, and the private sector facilitates successful cross-communication and provides an encouraging environment for start-ups. (5) Optics/Photonics – Arizona (Tucson Centered) Formed in the early 1940s to support astronomy in the area, the Arizona optics cluster has grown to employ more than 25,000 people. This size and strength has allowed the cluster to compete on the global scale with both small and large companies fulfilling the needs of many industries with optics. The cluster is buoyed in large part by two organizations: The Optical Sciences Center at the University of Arizona, which trains a large part of the workforce and has been cited with spinning out a significant number of startup companies, and the Arizona Optics Industry Association (AOIA), which provides a forum for communication and networking within the cluster. The AOIA has been perhaps the more important of these for its active role in recruiting optics companies for Arizona. The organization has drawn manufacturing firms, prototyping firms, consulting services firms, software companies and all manner of hardware companies to the region (Young, 2007). Companies operating in the optics cluster in Arizona were surveyed in 2007, identifying their top challenges as finding qualified employees, a need for market analysis, and local networking opportunities (Wiggins, 2007). The need for qualified employees is a bit surprising based on the close collaboration between the Optical Sciences Center and industry. The Center plans to expand its capabilities to train the local workforce, which likely needs more workers to support its growing size. The AOIA facilitated market analysis in 2007 to help alleviate the second challenge and holds monthly meetings and other events to promote networking in the area (Arizona Optics Industry Association). Key Takeaways: Clusters can form either to support a local research institution, or through movement of technology from local research institutions to private industry. Trade organization formation in a cluster area can have a significant positive impact on the success of a cluster. Large, established clusters can still have problems attracting talent. Cooperation with academic institutions can bring in new talent to help with the shortage. (6) New Media - Toronto Based on a PricewaterhouseCoopers report in 2000, Toronto’s New Media cluster is lacking a single, unified voice (Conrath, 2000). The nature of the new media industry is to constantly innovate or else collapse. Competition is regional as well as international, and Toronto’s cluster has strengthened its international competitive presence in the space by having new media firms collaborate among each other. However, the idea of firm collaboration materializes as firms age and mature. An additional 33% of the New Media talent pool is freelance workers, reflecting a unique characteristic of the new media sector and one which shares similarities to a typical firm within it: value is produced around a projectbased work schedule and a free flow of talent to supply these projects (Perrons, 2004). The talent pool and their demands for an excellent public transportation system are met well with the infrastructure of Toronto. Toronto government has also had mixed history with the new media cluster. Public policy has removed impediments to the cluster’s growth, for example allowing mixed use of former industrial areas for affordable new media space. However, complicated IP regulations and a failed, governmentrun marketing strategy of the cluster have tinged new media as well. Better yet, new media companies of Toronto would like business-market firms to offer best practices and better access to clients. Key Takeaways: After a critical mass of firms in a cluster is met, a unifying voice must brand them as a unified group As a firm matures & develops, it realizes the benefits of collaborating with like firms Certain industries naturally attract young talent; the transportation and economic infrastructure to support these individuals must exist in the cluster’s location. (7) Information Technology – Bangalore, India According to an article I the European Journal of Development Research (PIETER VAN DIJK, 2003), Bangalore, the capital of the Karnataka state in India, is the location of the first IT cluster in India. Government activity supporting the cluster, the large pool of inexpensive, skilled labor available, and quality of life measures such as climate and a ‘green’ label were major factors in the growth of the cluster. Karnataka was the first Indian state to establish a comprehensive IT policy. Through this policy, it created a separate Department of Information Technology to lead the efforts in the state. Infrastructure investment was made to set up Electronics City on the outskirts of Bangalore, and Software Technology Parks were created in a number of places throughout the state. State tax incentives were established for IT companies setting up in Bangalore and incentives are also provided by the Indian government for investments in Infrastructure. Karnataka also actively promotes Bangalore as the software capital of India, adding to the global brand image of the city. The size of Bangalore and the quality of education provided in the area leave the IT cluster in the city with a large pool of inexpensive skilled labor. There are a number of centers of science and technology and centers of higher education in Bangalore, each of which provides training and enhances the quality of the workforce in Bangalore. Additionally, the quality of life in the city is attractive to potential residents. Bangalore is located at an elevation of 3000 feet, providing a more moderate climate than those of other Indian cities. The city also has a number of green initiatives and citizens groups that work to use resources effectively and keep the city clean (Rau, 2006). IT is a relatively non-polluting industry and fits well with the culture in Bangalore. Key Takeaways: Comprehensive government policies, along with ongoing support and branding communication can create an environment where a cluster can grow. Quality of life measures in cluster areas can be important factor in the attraction of talent. Suggestions for Future Study Fix or replace public education system o No more studies on this, look for some action around this issue A cultural study of what’s important to people in NNM o Perhaps they don’t want to develop the economy and want to keep it as is, despite the government risk Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Scott Beckman, Monica Abeita, and Ed Burckle of the Regional Development Corporation, Steve Stringer, Belinda Padilla, and Steve Girrens of the Technology Transfer Division at Los Alamos National Laboratory, and all the participants who attended the public REDI meetings. The team would also like to thank the organizations behind the Santa Fe Complex and the Santa Fe Incubator for use of their facilities to hold the meetings. Works Cited (n.d.). Retrieved July 14, 2009, from Arizona Optics Industry Association: http://aoia.org/site/ (2009). Retrieved July 9, 2009, from Arizona Nanotechnology Cluster: http://www.aznano.org/about_us.html Aerospace Cluster Initiatives. (n.d.). Retrieved from Prosperity Partnerships: http://www.prosperitypartnership.org/clusters/aero/aero_initiatives093005.pdf Conrath, C. (2000, June 30). Toronto’s new media needs to speak with a single voice. itWorldCanada . Development Research Partners, Inc. (2005, October). BIOSCIENCE: Metro Denver Industry Cluster Profile. Retrieved August 1, 2009, from MetroDenver Economic Development Corporation: http://www.fbla-pbl.cccs.edu/0708Documents/bioscience_100805.pdf HBS: Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness. (2008). Cluster Profiles Project. Retrieved June 23, 2009, from Institute for Strategy and Competitivenesss: http://data.isc.hbs.edu/cp/index.jsp LeRoy Eyring Center for Solid State Science. (2008, March 3). Retrieved July 1, 2009, from Arizona State University: http://www.asu.edu/clas/csss/csss/ Murdock, S., Crosby, S., Stein, B., & Swami, N. (2003). Report of the National Nanotechnology Initiative Workshop. REGIONAL, STATE, AND LOCAL INITIATIVES IN NANOTECHNOLOGY. Washington, DC: National Science and Technology Council. NanoFab. (2003). Retrieved July 1, 2009, from Arizona State University: http://www.fulton.asu.edu/nanofab/ NWA Spotlight. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.wghalliance.org/pdfs/NWAmag_spotltseattle.pdf Perrons, D. (2004, January 1). Understanding Social and Spatial Divisions in the New Economy: New Media Clusters and the Digital Divide. Economic Geography . PIETER VAN DIJK, M. (2003). Government Policies with respect to an Information Technology Cluster in Bangalore, India. THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH , 89-104. Rau, P. (2006). National Barriers to global competitiveness: the case of the IT industry in India. Competitiveness Review. Seattle: History. (2006). Retrieved August 1, 2009, from Cities of the United States: http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3441801241.html Soder, C. (2008, May 21). State awards $143 million for tech research. Retrieved July 5, 2009, from Crain's Cleveland Business: http://www.crainscleveland.com/article/20080521/FREE/561134561/1048&Profile=1048# van der Linde, C. (2003). The Demography of Clusters - Findings from the Cluster Meta-Study. In J. Brocker, D. Dohse, & R. Soltwedel, Innovation Clusters and Interregional Competition (pp. 130-149). Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer. Wiggins, G. S. (2007). Moving Optics and Nanotechnology Forward in Arizona. Office of Economic and Policy Analysis. Young, A. (2007, May 8). The Arizona Optics Industry Association. Retrieved July 10, 2009, from http://www.optics.arizona.edu/OPTI696/Sp%202007/TermPapers/AOIA%20by%20A%20Young.pdf Appendix A: Past Studies & Reports Masquelier, Mike and Nathan Furr. New Mexico Ecosystem Report. New Mexico: McCune Charitable Foundation and New Mexico Community Capital, 2009. Print. New Mexico State. New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson’s Office and New Mexico Economic Development Department. Technology 21: A Science and Technology Roadmap for New Mexico’s Future. Santa Fe: New Mexico Office of Science and Technology, 2009. Regional Development Corporation. Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan. Santa Fe: RDCNM, 2009. van der Linde, Claas. “The Demography of Clusters – Finding from the Cluster Meta-Study.” In: Brocker, J., D. Dohse and R. Soltwedel (eds.) Innovation Clusters and Interregional Competition. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer, 2003. 130-149. Appendix B: A Case Study of Research Triangle Park North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park (RTP) is frequently referenced as one of the nation’s most successful clusters. It is home to nearly 100 companies in high-tech industries from biotechnology, to crop sciences, to computing, providing high-wage jobs to nearly 40,000 employees. Originally, the concept of RTP was created by a university professor and a local businessman interested in keeping the locally-educated graduates closer to home. Today, references to RTP usually do not mention the odds the park faced when it was just an idea or in its earlier years. But the odds then were similar to those facing the many regions today, including Northern New Mexico, that are undertaking similar economic projects. For that reason, while our recommendations are customized to local factors of Northern New Mexico, the RTP story offers useful examples, motivations, and takeaways for this region’s leaders as they continue this new effort. Characteristics of the RTP region in the 1950’s: Geographic, demographic, and business challenges: The triangle region sat between, but was not integrated with, two economic engines for the state: The timber belt to the west, supplying the state’s furniture industry, and the agriculture belt to the east. In addition, the furniture and tobacco industries were joined by the textile industry as three clusters of businesses set to begin a decades-long decline. The cities of Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill sat divided by a forest expanse widely considered to be land that could not be developed. No four-lane highways existed between the three cities (Durham, Chapel Hill only 10 miles apart, with both approximately 30 miles from Raleigh). One-hundred fifty miles to the southwest, the city of Charlotte presented intra-state competition to the cities of RTP. The RTP region did not offer the same employment prospects as Charlotte or other locations such as Atlanta or Washington, D.C. Political landscape: State governor Luther Hodges was immediately supportive of the idea once local leaders briefed him on the plan in 1954. As a former private-sector executive he would later exploit his contacts in the northeast section of the country once the park began actively recruiting businesses. Hodges gained support for the effort in two ways. He commissioned a study to evaluate the idea of RTP in depth. As the study progressed, the public gained greater awareness of the project. In addition, the governor frequently rallied support for the park by declaring that North Carolina had to reverse the ‘brain drain’ of local graduates leaving the state. With few exceptions (the aforementioned study being one), Hodges did not use state tax-payer dollars to fund the effort. However, the North Carolina secretary of state negotiated a taxexempt status with the IRS for RTP’s for-profit branch that made profits on land rentals. Involvement of private industry, universities, and citizens: The key reason the project did not rely on taxpayer dollars was the enthusiasm of state business leaders at the executive level. RTP was originally owned by Pinelands Corporation—a company chartered by local business leaders—which sold stock to fund land purchases. Pinelands faced financial distress in 1958, partly because the region’s universities were still uneasy about involvement in a commercial venture. Wachovia Bank’s Chairman of the Board, Archie Davis, set out to appeal to state citizens’ public spirit. He worked tirelessly over several months to solicit donations eventually totaling $1.25 Million. With financing secured, local leaders created the non-profit Research Triangle Foundation of North Carolina. The foundation assumed all of Pinelands’ assets and liabilities and, importantly from the standpoint of gaining support, control of the foundation was placed with the local universities. Key takeaways applicable to the Northern New Mexico project: The project required sustained effort from enthusiastic visionaries in private industry, local research institutions, and the public sector. The project only succeeded once the research universities offered full support and resources to it. The project faced several setbacks initially, but with a broad base of support, it overcame those setbacks through perseverance. Once the project began to succeed, it still took two full decades to ensure the park’s long-term viability by attracting enough tenants and supporting entrepreneurial ventures with wet-lab space, computing resources, etc. A key factor keeping universities committed to the park into the 1960’s and 70’s was the Triangle Universities Computing Center. Home to one of the fastest computers in the world, operated by IBM, it became a way for RTP to address universities’ data processing needs. This assistance was extended not just for administrative tasks, but also for student projects – further building future graduates’ interest in the region. The New Mexico Computing Applications Center houses Encanto, a supercomputer available for pay-per-use and initially funded by the state, which could be used in a similar fashion. Appendix C: Full List of Considered Tactics Branding Brand NNM as one of a culture of innovation. Anchor this claim behind the national laboratories and strategically leverage Albuquerque as a proximal asset for travel, capital, and academic resources by way of the Rail Runner Seek out motivated, independently-minded entrepreneurs of the “Young Professional” demographic (ones that aren't married to the Silicon Valley culture of San Francisco) and try to lure them to the region by highlighting NNM’s natural strengths Create a web-video (youTube subscription channel with updates periodically of new videos) & TV video campaign highlight NNM as technology hub Publicize the real success stories from local high schools, e.g. - grads that go on to do great things, internships/coops that are great during high school, etc. Make people think about good, not bad, aspects of NNM public education Quarterly newsletter describing activities and updates of the REDI implementation plan Press releases on RDC website and column in local newspapers about the latest developments of technology in NNM Develop a job database, regularly solicited from NNM tech firms, which RDC people can use to recruit people to NNM Networking Harmonize the Northern New Mexico professional networks into one communication medium Consortium of business leaders who can work with local colleges to help them understand graduate needs in future - get programs to meet those needs Target the Young Professional demographic to NNM networking events, via free food and spirits, in order to invigorate the attendee presence and bring in fresh ideas LANL career fair in NNM (academia and industry) Government Extend tax relief to all types of small businesses, building on the tax breaks available via New Mexico Partnership. Develop a repository of completed grant work within the state (grants funded by the state for research, those funded by in-state universities, or those funded by the federal government and completed in New Mexico). Make the repository available as a ‘knowledge source’ for university researchers and students to access. Sponsor lab-space in local universities and research institutions for students and professors to pursue further advancements of the grants’ scientific results. As a model, the National Science Foundation recently awarded University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill money to fund a similar effort. Information may be found at: o http://uncnews.unc.edu/content/view/2537/138/ Establish more grants that give would-be entrepreneurs money to pursue a business project. o Several members of the NNM business community expressed concern at the lack of funding available (as grants, loans, or small equity investments) to develop their businesses after they have run through initial funds from sources such as LANL’s VAF awards. Their concern is that if their ventures are perceived as ‘too risky’ by venture capitalists or earlier-stage angel investors, they will run out of funding to develop prototypes, initiate manufacturing, or undertake other critical business functions. ChangeExamine and change regulations or policies that promote taking a business out-of-state. In context, this would mean reviewing where New Mexico regulatory standards are more stringent than the 50-state average, thereby indentifying industries that may be discouraged from moving to, or staying in, New Mexico.your business out-of-state. Understand NM's level of stringency on policies v. national average, as benchmark Increase the allowable percentage of the Severance Tax Permanent Fund that is used to fund Small Business Development in the state. Allow businesses that are just a bit bigger than one or two people, and have just gotten a grant, to stay in incubator longer to gain footing Technology Action Plan Lead Organization: New Mexico Technology Council (NMTC), Jeff Lunsford, President Background and Overview In 2009, Los Alamos National Laboratory’s Technology Transfer Division sponsored a Technology Cluster Strategy, lead by LANL Proctor & Gamble Industrial Fellow Steve Stringer and LANL MBA Students. The Strategy identified numerous strengths for the cluster, including LANL and SNL, and a concentration of research and development activities and companies. Recommendations included branding and networking to unify often disparate and uncoordinated efforts within this broad cluster, in order that the cluster can mature and develop more depth in the value chain. The Strategy identified the New Mexico Technology Council (NMTC) and its Northern NM Chapter as the lead organization in this area. Through financial contributions of the Technology Integration Group (TIG), a major LANL subcontractor, NMTC is developing a single, unified Technology Cluster across various industry sectors for the entire state. NMTC has two existing chapters in central and northern New Mexico through which it implements networking and education programs. In order to grow its membership and develop a single voice for technology-related businesses, NMTC needs to evolve from a largely volunteer organization to one with paid staff. This will require $40,000 from REDI partners to expand the cluster in Rio Arriba and Taos counties and to attract more young professionals and tech-savvy youth to the NNM Chapter. GOAL & OBJECTIVES Grow and strengthen a single, unified NNM Technology Cluster - Expand network of private cos. in the cluster - Grow institutional capacity of the cluster - Increase public awareness of the cluster and its regional impact SCOPE OF WORK MEASURE 1. Hire full-time staff person 30 days from receipt of funding commitment. 2. Outreach to regional tech companies. 3. Constant web presence on NMTC site, Facebook and Twitter. 4. Develop 20-25 profiles of regional tech companies, young professionals and tech-savvy youth. 5. Establish Leadership Council for NNM NMTC Chapter 3 months from receipt of funding commitment, to ensure all tech cluster activities are coordinated. 6. Host networking events for the Tech Cluster, and expand these into Taos/Rio Arriba counties, depending on the success of outreach efforts there. 1. Increase NNM individual memberships by 15%. 2. Increase NNM corporate memberships by 10. 3. Increase corporate memberships in Taos/Rio Arriba companies by 5. 4. Increase individual memberships by young professionals by 50. 5. Event attendance (total and by event). 6. Number of web and print articles. 7. Number of website visits. FUNDING LEVERAGED_________ Committed: $55,000 Technology Integration Group This currently funds: - $15,000 in NNM Networking Events (Beer & Gear, Supercomputing Challenge, Fractal Foundation, etc.) - $15,000 in Educational Initiatives (21st Century Classroom, etc.) - $10,000 Tech X Annual Event (includes $3k in scholarships) - $10,000 Women in Technology Event (includes $3k in scholarships) - $5,000 NMTC Membership Pending or In Process: $15,000 Consortium of LANL Major Subcontractors REDI Requested Contribution: $40,000 c o