ANSWERS TO REVIEW QUESTIONS – CHAPTER 10

advertisement

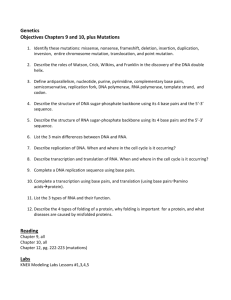

ANSWERS TO REVIEW QUESTIONS – CHAPTER 10 1. Describe the experiments that showed that DNA was the carrier of genetic information. (pp. 217–218) See pages 217–218 and Figures 10.5 and 10.6. Briefly, in 1944 Avery, McCleod and McCarty mixed a dead virulent bacteria with a living but non-virulent strain of the same bacteria to demonstrate that DNA and NOT protein or any other cellular component was able to change the non-virulent living bacteria to the virulent form. This process of absorbing DNA from outside the cell is called transformation. In 1952, Hershey and Chase used radioactively labelled DNA to show that when a bacteriophage infects a living bacterial cell it transfers ONLY DNA to the bacteria, and that this DNA is passed from parent to progeny. These two experiments proved that DNA is the store of genetic information. 2. How does the structure of DNA enable its role as information carrier? (pp. 218–219) DNA is made up of four basic building blocks—adenine, guanine, cytosine and thymine—linked by phosphodiester bonds. It is the order of these nucleotides that enables DNA to store information. Because the billions of nucleotides can be ordered in many billions of different ways, the potential information that can be stored is enormous. For instance, just four nucleotides can be ordered in 44 or 256 different ways, each encoding a different potential peptide. 3. (a) What are the names of the DNA sequences that start and end DNA replication? (pp. 221–222) The start and stop sequences of DNA replication are called origin of replication and terminus of replication, respectively. (b) Construct a flow diagram to show the four major steps in the complete DNA replication of prokaryotic genome. (pp. 219–220) Initiation of replication Unwinding of the double-stranded DNA Synthesis of the new DNA at the replication forks Termination of synthesis 4. Using a diagram, explain what is meant by semiconservative replication. See Figure 10.8. 1. (a) What is a replication fork? (p. 221) A replication fork is the site at which nicking of one strand of the double-stranded DNA occurs. This nick is introduced by the enzyme DNA gyrase and is the site of new DNA synthesis. (b) How does replication differ between prokaryotes and eukaryotes? (pp. 221–227) DNA replication in both occurs by semiconservative leading and lagging strand mechanisms. There are, however, many differences between eukaryote and prokaryote DNA replication. In particular, in eukaryotic DNA replication the primers of DNA synthesis (Okazaki fragments) in eukaryotes are smaller, DNA synthesis on leading and lagging strands is performed by different polymerases, the replication fork moves 20 times more slowly, the chromosome has many origins of replication, and special mechanisms must be in place to replicate the 5' ends of the linear chromosomes. (c) What is the advantage of the many sites of replication found in a eukaryotic chromosome? (p. 226) Multiple replicons enable the eukaryotic chromosome to be replicated much more rapidly than would be possible with a single replicon as found in prokaryotes. 6. RNA synthesis is an important component of DNA replication. What role does it play? (p. 224) DNA synthesis is carried out by DNA polymerases by the addition of dNTPs onto the 3' end of a growing DNA strand. However, these enzymes cannot begin synthesis on a single strand of DNA— they must have a template with a free 3' OH at the end. In DNA replication, particularly lagging strand synthesis, the 3' OH groups are provided by the synthesis of short RNA fragments that act as primers for DNA polymerases. These RNA primers are removed before DNA replication is completed. Consequently, DNA replication would not occur without RNA synthesis. 7. Why is DNA ligase essential for DNA replication? (pp. 222–223) As the lagging strand of DNA is synthesised in a discontinuous fashion from RNA primers, once the RNA primers are removed there are gaps in the DNA sequence. These gaps are filled with dNTPs by DNA polymerases, but the lagging strand still consists of fragments that must be joined. This joining of adjacent DNA fragments is performed by DNA ligase resulting in a continuous DNA strand. 8. (a) Describe the differences and similarities between E. coli DNA polymerases I and III. (p. 222) See Table 10.2. (b) What different roles do they play during replication? (p. 222, Table 10.2) DNA polymerase III is the main enzyme that carries out the addition of DTPs during DNA replication. The main role of DNA polymerase I is to remove RNA primers, fill the resultant gaps, and remove and replace any incorrect DTPs added by either itself or DNA polymerase III. 9. How do histones contribute to the construction of a eukaryotic chromosome and what happens to them during DNA replication? (p. 216) The small, basic histone proteins interact with the negatively charged DNA sugar-phosphate backboneforming nucleosomes. Histones are important for the tight packaging of the large DNA molecule (chromatin) and in controlling the expression of genes. During replication the histone proteins (primarily H1) are modified to alter the strength of the histone/DNA interactions. 10. (a) What are telomeres and why are they necessary? (pp. 226–227) Telomeres are highly repetitive DNA regions that may be many thousands of base pairs in length, located at the ends of linear chromosomes in eukaryotes. They are important in the replication of the 5' end of the DNA strands. (b) How are they maintained? (pp. 226–227) In somatic cells the telomerases are not maintained and are shortened during every cell replication cycle. Consequently, after a finite number of cell cycles it is possible that the entire telomerase will be removed and future replication will lead to the loss of the non-telomeric regions of the chromosome and eventual cell death. In germ cells such as sperm, an enzyme/protein/RNA complex called telomerase functions to add telomeric sequences onto the ends of the chromosomes.