transcript (doc - 100kb) - Department of Education and Early

advertisement

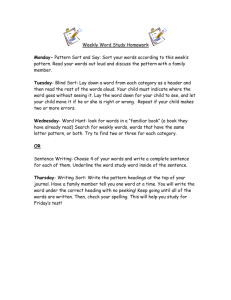

Diverse Learning Victoria University Angela Daddow, Amanda Carr This presentation was part of the 2011 DEECD Innovation Showcase on 13 May. This podcast is brought to you by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Victoria. Speaker 1: Good morning. Is it still morning… afternoon? I’m Angela Daddow. Speaker 2: And I’m Amanda Carr. Speaker 1: And we are both from Victoria University, although we are from different sections of Victoria University. I’m from the Curriculum Innovation Unit and my focus is around curriculum innovation, however I do have a background in social work, and social work and community services education and vocational education as well. Speaker 2: I teach academic skills and research skills, academic discourse in a multi disciplinary area, where we prepare students for entry into the arts. Speaker 1: Yep, we are going to talk about a program that we were involved in last year, as well with a couple of other colleagues were part of our team where we enabled students… we developed a pedagogy to enable students to develop quite complex writing skills and abilities while they were actually studying their discipline in the diploma, so slightly different model to what’s traditionally used, so we are going to talk a bit about that. Although we are presenting, sort of, in a tertiary context, we’re hoping that you’ll be able, that we… you will be able to stimulate your thinking a bit and you will be able to apply some of the elements of the pedagogy, or some of the thoughts and ideas into your sort of context as well. I’m not sure if… most of you might know about Victoria University, but I’m just going to give you a really quick sort of runthrough. We have 11 campuses most of which are in the western suburbs of Melbourne, some in the city, and of course you probably all know that the western suburbs have the most, well… a very high proportion of low socioeconomic groups as well as a very high cultural diversity. And we have quite an explicit appreciation of diversity in our values, where we see it as contributing to the richness of… and creativity of learning environments, and also around equity for students and staff. In fact there are few universities in Australia that are as diverse as we are. We are a dual sector university which means we deliver both higher education, further education and also vocational education - TAFE as it is more commonly known. But our university in Australia has the highest representative of both groups of students from low socio-economic groups as well as from culturally 1 and linguistically diverse backgrounds. So we’ve sort of had to do a lot of thinking around diversity, around learning and diversity and what actually works. There are a whole range of programs and this is one of them. You are also probably aware that the current, sort of, government policy around tertiary education is to increase participation, particularly of groups of students who are not normally represented, so Indigenous, low socioeconomic groups, people with disabilities etc. In our experience, nontraditional students often find universities quite alienating even at the vocational TAFE education level, it often has expectations that are quite foreign, and language and discourse that’s quite, quite, well alienating. And we’re aware of the risk of creating an underclass of students where they actually feel more inadequate than empowered, and we’re also aware of the sort of, the reality of differentiation between - social differentiation between people who have the advantages of some congruence between their backgrounds and, and the education environment, the learning environment in which they find themselves - I mean, it’s true of schools as well. We’re going to start with our experience of diversity and, and the beginning, the early beginnings of this project with a story. And the story starts from when I was actually a program manager in community services, and I had in my office a tall mature age black African man from Sudan, and he was in my office with his, one of his teachers and a student support worker… and he was very angry. And one of the reasons he was ang... well, I will tell you why he was there before I tell you why he was angry. He was there because he was about in the 2nd year of his Diploma in Community Development, he was about to go on his final placement and he was about to transition to… towards graduation. And he’d passed all his written work - am I too close? he passed all his written work… actually it was distinctions by this stage… he had progressed quite a lot there was no obvious plagiarism, however when we got him to do ind... and other students to do independent writing tasks in class, he was actually writing like a primary school age person. When we tried to delicately explore this disparity, he… his dignity was quite affronted and also he had done what we asked, or what we had suggested earlier on in the class, in the course. He’d gone to other parallel English language classes, he had gone to what we call Concurrent Assistance, which is like our student support service, but he had gone every day - he was in the office every day getting assistance with his work, he’d immersed himself in the discipline and sort of, as we sort of tried to do it in a trial and error kind of way and hope people would pick things up. So he’d done all those things and now we’re saying ‘Hold on; you’re getting distinctions but we’re worried about your work -readiness and your readiness to go into placement’. So, it was after, after thinking about that conversation, not fully resolving it, that we… I decided to make a phone call to our language and learning area in the university - and we are fortunate to have a very highly effective one - and we started to explore what we could do for students because this was not uncommon and it wasn’t only CULD students, students who come from cultural and linguistically diverse backgrounds, it was actually students who were quite unfamiliar with academic discourse, students who were first, first in the family at university and we had quite a lot of those, students who perhaps, particularly, I guess, in vocational education who had not necessarily succeeded all that well through the education system, so they 2 weren’t terribly comfortable in that sort of environment. So it was not uncommon, so we started to explore what we could do to, to progress these students more effectively and not leave them in this situation, and us, in a way. The reality with diverse students is we can’t assume any fixed starting point, and similarly we can’t actually assume a fixed end point, but at the same time we don’t want to lower standards. So this creates our dilemma and particularly around English language and literacy areas, because the traditional approach is, we’ll get some literacy or English language teachers in, we’ll try and fix their grammar. But of course they’re all at different places, the grammatical sort of errors or, or differences, or expressions are at different places, so it’s actually fairly inefficient to try and just come in and fix grammar, and that’s often separate and disconnected with the actual discipline. And we also didn’t want to perpetuate the deficit model, really, of ‘you’ve got something wrong with you and we are going to fix you’, so we wanted to try and explore alternative ways, ways of addressing the problem. So we turned to, well, some of you may be aware of the socio-cultural theory of learning, where… instead of seeing knowledge as some sort of fixed point where people enter some kind of learning environment, they absorb some information, concepts, and then they go out the other end with those somehow internalised… Instead of seeing knowledge like that, we thought about knowledge as being held amongst knowledgeable people in, in, in ways that they communicate with each other through language and text. So if knowledge is held in these communities and we - and they’re… they’re called discourse communities - how do we help or support and scaffold nontraditional students to actually start to participate in that discourse community? Learning then becomes a process of the student becoming a user of that specialist discourse, and a learner becomes a growing participant in the knowledge community. Now, that participation happens at different levels and in different ways that we can talk about and we’ll demonstrate it a bit later. As you are aware, academic disciplines are even in… you know, again a diploma level 2, which is sort of pitched at first year university, the disciplines, the discourse communities are highly analytical, they’re very focused on writing and they’re analytical and they’re critical. And these are the sort of areas that are quite often, often quite foreign to less traditional students or non-traditional students. To participate in those discourses, it supports students or helps them find places of, of empowerment and those who are not well supported to or, or scaffolded to participate conversely become disempowered. Again, we didn’t want to reinforce it through our curriculum and our teaching practices and our pedagogy we didn’t want to reinforce that disempowered sort of model. Related to the notion of discourse community we also looked at… actually at identities. Our identities are formed, obviously, as we know, often through the discourses of our cultural, geographic, social, language backgrounds. And I guess you can think about that in terms of the, you know, thinking about teenagers from four different parts of the world, Hong Kong, Northern Territory, Melbourne, Papua New Guinea Highlands. So the, our actual 3 identity is formed very much through language and discourse with the inherent sort of power relationships that exist in those. Now when… when people come into discourse communities of… in the tertiary environment or even the secondary education environment particularly at the upper levels, they’re actually being drawn in to, to, to shift, make some identity shifts, to particularly using writing and text as a medium for that, but there are shifts in identity and we would argue that non- traditional students actually have greater shifts in those identities to make than more traditional and, and differently resourced students. These concepts come from critical literacy. I’m going to hand over in a moment to Amanda who’s going to talk about some of the specifics and the practicalities of the, the program and also show you some student work, because we have been actually really excited by the some of the shifts in student writing and we’re in a process of… just about to set up some formal evaluation because of the findings have been quite exciting and not only from CULD students but also from Anglo students who have actually found it quite transformative. I just want to say before I hand over to Amanda, I just want to clarify that we, we - trying to think where to start - all students who did the diploma participated in this program, so we didn’t select out any, any particular students - all students - it was mainstreamed into the program. The only people who were excluded were those who had a ‘recognition of prior learning’. So, we had existing core units - sociology and communication - so everyone had to do them, and we actually had language teachers teaching the writing components in the communication unit, and we imported an academic skills and skill development research unit from another area as an elective and all students were required to do that. And that’s, and in that imported unit the sociology material was deeply embedded into the writing skills, but I’ll let Amanda sort of talk to you about that in a bit more detail. Speaker 2: Thanks, Angela. This was a process of what we call embedding, but the way that the communication unit went into the sociology was from our point of view an adjunct subject, and it gives you the impression that these two are firmly linked and on an equal basis. I’m going to talk about the nuts and bolts of how this worked, because I was the teacher in the classroom at the time. I’ll start… I want to start with the idea of collaboration and how that worked. We were actually working within a grant project and so there were two teachers from the language area and two from the sociology unit, and when we met together it was really important to go through what Angela has just talked about, and that is the theory of knowledge, and particularly, I guess, from our point of view it was really important that the sociology teachers saw language as being very much connected to the knowledge that were teaching in their classes, but likewise it was really important for us to see sociology as the discipline that we were totally contextualising the language into. So the first meetings were about explaining the context, the concepts of sociology that were important to the sociology teachers, and this could be of course relevant to any particular discipline, so it’s not necessarily just linked to sociology although sociology in… in a… I guess… is a highly theoretical sort of discipline and so that was sort of important for conceptual development. 4 The first things that we looked at were the assessments, and we were trying to… and I will show you something in a minute about that… but we were trying to step the development of students writing in tandem with what they were actually learning, so the more theories they were learning, the more they were able to develop their language into, say, from reflection - talking about the self - to argument, where they’re talking about competing theories. The writing tasks that we developed for the language class were all about developing the identity. So… and I’m going to show you quite a few texts of students and show you how they stepped out that change of identity from the sort of the naïve known world that they were… came into the course with all their diversity… into a very unifying and cohesive world of the academic sociology world. In particular we also looked at the selection of readings, so instead of just having a whole lot of academic readings that were good for theory, we looked at text in terms of language, and I will talk a little bit more about that, too. All right, this is really just a pictorial outline of what Angela has already talked about. As you can see, texts were really fundamental and really central to our idea of… to the materials and the activities that we were using. Students were supported to see themselves as participants within the texts. We were interested, as I said, in looking at what people do inside the text. So the experts use predictable forms, they have a repertoire of key words or concept words, they evaluate competing theories, and all of these ways of participating in the text are actually contained in the features. So you can see… we started with reflection - that’s because reflection was really meeting the student at the point that they were at coming into the course. If you think about the diversity, one of the things that they have in common is their experiences, so we started there, linking just one theory to their experiences. We moved out into an oral presentation – thanks - we moved out into an oral presentation where we were representing students… students had to represent theories at work. Then, again moving out from the self, we were looking at the real world and we decided to use a case study, still just applying one theory to that world. Finally, and this, I guess, was the be-all and end-all of the academic participation, they were asked to write an argument essay where they were using competing theories to… positioning one against the other and entering into debate. So now I would like to go into what we actually did and some of the assessments and step you through the process of looking at one in particular. The first one, and to show you what was expected of the students, and how they did it… When we looked at the first reflective essay, we said, “Well… the sociology teachers said… “ok; what we want students to be able to do is to apply sociology, the sociological imagination… we want them to describe the self, and they need to be able to do that in terms of functionalism, whatever that is, describe, discuss experiences and use academic style and conventions. When you look at these criteria you can sort of see that the first two deal with knowledge, which might be picked up in, obviously picked up in a sociology class, but the second two are possibly to do with language and may just be left up to chance. Particularly the last one, often, was just a case of 5 immersion or perhaps concurrent assistance in a worst case scenario. When we looked at those criteria, we sort of re-imaged them - we saw them from our own point of view and we shared that, and we also looked at how we were going to teach these sorts of skills but not just the academic conventions. We weren’t just interested in being delegated the language, and that had never worked, so we looked at the first two criteria as well, and using the socio-cultural theory of knowledge we were sort of saying “Well, if they need to look at and sort of unpack something with functionalism, they are going to need the language of that, and so the text that they need they are going to be gathering functionalist discourse as well as learning what it is. Also, with reflection, if you think about it there’s two voices there - if you are unpacking your own life, you’re the unpacker, you’re the, the - you’re looking at this from a perspective of detachment but you’re also looking at yourself. So really you’ve got self and expert in the text… now, for students that’s a really difficult thing for them to do. Who is who in the text and of course the classic question that students ask is ‘do I put ‘I’ in this text?’ ‘Can I write ‘I’ in this essay?’ And so we’re really going to cope with that idea there. Of course the expert was going to be the one with the new language. Case and theory, where do they go? If I put theory first, what does that make me look like?” “Well, it will make you look more like an expert - if you put yourself first in the paragraph then you’re going to be coming from that more naive position. So we were going to talk about that with them. And the conventions were very much handpicked, particularly for this reflective exercise, and we looked at normalisations because this is what carries weight in academic writing, where if you normalise something, you make it into a thing, a concept, then you can start showing how those concepts are relating to each other. They might have a cause and effect relationship, they could have a problem/solution relationship, maybe it’s just sort of a classification, but they have to be things that can’t be what you ‘do’, ok? This is one of the very first things we did in class, and it was dealing with the first criteria, this idea of the sociological imagination, which is really just looking at the world through the eyes of a sociologist, seeing it the way they would see it instead of from your own perspective. We started off with these open prompts where students are just writing stories about themselves so we asked them, say, “Tell me about a time when you felt nervous”. Or “tell me about a time when you felt that you changed”. And when they wrote these narratives, we’d then say to them, “Ok, what we need to do is we need to reimage and re-form things out of your experiences”. And so, as you can see, that perhaps from this point, from this particular example - a teenager here where everything changed - is a sense of identity, and a trip to the beach, they can be seen as employment patterns in Australia. You know, cultural habits and recreation, again a summer trip, not everybody goes to the beach, etc etc. Once we did that, we asked students to rewrite their text, and to use those conceptual words as sort of, the lynch-pin between the way that the sentences were going to hang together. And this was a sort of typical example, where they found the one that was perhaps the most generalised concept, sense of self, and then they showed the relationship between the different parts, the different concepts ain that. And this was really just the first step towards to starting to write outside of their own experiences. So we 6 had a couple of steps in the class for this first partic... this first piece. First of all, we didn’t just have our theory in our heads and sort of taught to that pedagogy without the students being any the wiser. We did tell them what we were doing, we did talk about how the more that they write, and use these text features, the more they are going to feel part of a certain community and that was sociology. So we were very explicit about what we were doing, to the point where we would say, “Well, when you write this sentence, who do you think you are? Who are you being?” We looked at topic sentences as things that academics do in order to really break up very dense complex text, sort of like a ready reckoner - when they read through it they can just read the first line - do I need that? No, I don’t. Keep going etc, that’s often the way we read academic texts. And so this idea of reader and writer being very much interconnected was openly discussed. We looked at ordering techniques, and creating these answers to problems, which is something that academics particularly like to do, build knowledge, create a better world etc, and the editing and proofreading. Ok, I’m going to talk about a particular…this is a student who I have called Mia, and this is how she did it. She was asked the question ‘How do you think you’ve changed?” And she responded, “Well when I became a mother of two my life has changed”. This student was a CULD student, so she was… the English language was not her first language but she did have a good education in own language. What she does here is that she‘s again got her narrative and we asked her to open the back of her sociology textbook, you know, a tome like this with a whole… you know section of, ind... a whole index of these conceptual words. So she looked up the index and was able to find conceptual words from that, that she could place against her narrative. By doing that, she then was able to discuss these with oth... other students and teachers and just go through her class readings to make sure she had everything in place, and then she… after a couple of goes wrote this and followed the same method that we taught where all of those conceptual words were put in the heading, so that she was telling the reader what she was going to talk about, then she used the ordering techniques to do that. As you read you will see that she’s got ‘firstly’, ‘secondly’ and in the final paragraph, or in the final sentence I should say, she talks about the answer to this problem that she’s posed. You’ll, you’ll see that there are some grammar unconventional grammar mistakes there, and this is the typical… this is actually typical of what remains, I suppose, after we follow this process, which is why the editing and proofreading at the end is very important. And when you think about it, academics or writers, when we first write something for publication or as a report, it’s not that we get it right the first time. And what we do is we give it to somebody else or we have a look at it after a little bit and we fix those mistakes. In fact we had an ESL teacher come in specifically for those sessions just to fix up the grammar, instead of doing sort of a blanket coverage of grammar that may have had a sort of hitand-miss value, might have been good for a couple of students but possibly not everybody. This… once we started to show the steps to the students, we actually looked at the real assessment and this is where we weren’t making up extra assessment for our particular study, so they didn’t have extra to do - they had 7 their sociology assessment, we were adjuncts -so we were dealing with that as well. This student says “I came from a family of three children; my parents are very strict. When we grew up and we helped in the house chores at early stage. And in our family we would look after the parents when they are old. Most families in my religion look after the old people so we have many children”. And this was a response to the initial assessment question where she actually had to write six hundred words on looking at herself from a functionalist point of view, so we started here. We - following the steps again and doing the reading, but don’t forget she was also having her sociology classes at the same time building knowledge there, and the teachers, being more aware, were also helping with the languages as such, she wrote “Functionalist like Murdoch believe that children are an investment in the future. As children mature the economic value of the family is likely to increase, in my case we were three in the family, we helped in the house chores at early stage, my parent had expectations that we would support them when they were old. The reason behind this was mainly because of our religion, therefore functionalist would agree with the idea of having family and my children, in my family that it is a big incentive, incentive to a family thus results to my family being functional in this scenario.” So what went into this student’s writing? Well, the steps that I was, been talking about, but the most important thing here is that this student is sending a clear message that she belongs somewhere. She belongs to some sort of community, a discourse community the way that we had envisaged it, and this particular one - sociology - because of the key words ‘functionalism’ etc there. She’s read functionalist texts, Murdoch etc, but she’s also made some sort of more generic academic convention moves. She’s not only saying she’s part of sociology but academia in general, by the fact that she’s changing her vocabulary from the phrasal verb form to the more Latinised verb, which we discussed in class. She’s using signalling language – she’s reaching out to the reader and saying “This is how I want you to read this”, so she’s actually being quite empowered in her text. And she’s, she’s signalling that she belongs to a certain club by using academic conventions, not just referencing - she’s managed to get the technicalities right there but she’s also being very careful with what she’s saying, she’s being tentative in “This scenario is likely to…” so she’s not throwing out these generalisations and saying the world is black and white. Ok, I’ve talked about how they were doing quite a lot of reading as well, so I just thought I might mention what we did with the reading in this class, because texts really held all the keys for these students. When they read text they weren’t just reading them for knowledge. We didn’t just say “Well, you know, learn this theory”. These texts were here and written by people who were potentially in the same club as the one that we were ingratiating students into. So they were asked to see writers as potential colleagues, members of the same group, and in this case they were asked to look not just at the language, sorry… the knowledge… but at the language, and every time we read texts, we read them in order to harvest, to gather all of these language and text features that make people soon say, “Oh yes, you belong to this or that particular area of discourse.” And so annotation was a key there. We used prompts to tell… to say to the students “Well, when you read 8 something I want you to ask: what is the writer doing right here, right now? Are they challenging somebody? Are they comparing something?” so they’re… sort of gathering also ideas about, “Oh, this is what, this what you do, this is what academics do”, and relating to that. They were also asked… “Well, if you read this paragraph and it was a book, what would be the title of this paragraph?” So instead of just saying, “Oh, what’s the… what’s the main idea here?” they actually had to sort of think about themselves as if they had written that text as well. And my personal favourite, and the one that got a quite a few giggles: “If the writer was in the room right now, what would you say to them?” And this solicited a really sort of, personal response, but personal in the sense that they were willing to go head-to-head with the, the writer of this and say “Well, you know, you can’t write this or you can write this”, or etc etc. They were talking to or thinking about the writer as part of their discourse community. The link, the bridge between writing and reading or reading and writing in this case is often tenuous but what we try to do here is… when they had the sort of text that they had to write as in an essay, we actually co-authored with our, our colleagues in sociology, a lot of model texts. And then with those models, we were able to say “Well, you know this is what we, this is the sort of thing that people write when they’re in your position, and let’s just have a look at exactly what they’re doing”, so with a text like this, which is sort of an essay text, we’d say “Well, we want you to show me, we want you to show us the words that the writer is using to link the theory to the story, because it’s a case analysis, ok? And that’s what you do when you do case analysis - circle all the tentative language, show me where the writer’s being very careful about what they’re saying. Also what are the key content words and which sentence is out of place? So we put in out-of-place sentences there as well. And by this, the students were able to recognise both the good and the bad in academic writing. And transfer it and write their own text according to these sorts of, sorts of knowledges. Shall I keep going? Speaker 1: I’ll take over if you like. Speaker 2: OK. Speaker 1: Thanks, Amanda. Ok, so the combination of… of particularly in this subject, was an…an essay around argument, which is what students often find so problematic. I guess one of the side benefits of this process was not just… well, the progress in writing as you have been able to see, quite complex writing, but has also introduced the notion that there’s no one single truth or one reality, which is sort of imperative in community services and social work etc - community development, where we encouraging a lot of analysis of, of concept, situations, context, people. So… and being able to, to view multiple realties and then make sense of those so it actually prepared students very well for the field, so it wasn’t, we weren’t just preparing them to progress to higher education cause some of them wanted to graduate with their diplomas 9 and actually practise in the field, it was actually preparing them through reading and writing text vocationally as well as… starting to build that sort of critical analysis skills, which we believe’s important in the field. Next one. Speaker 2: With the argument - I’ll just continue there - we’d some, in our, in the academic discourse area, the debate and building knowledge through debate but ultimately to achieve a sort of consensus, and then if you put that into a vocational area action, was, I guess, the final thing that we did with them, and it’s very confronting for the students… it was one of the things that they were… found the most confronting. So we really wanted to focus on also the skill of paraphrasing, because when you’re looking or debating in an academic environment you’re not really putting out your opinion. It’s not like writing in an opinion piece - it’s really just showing what the moves are, what the knowledge and the competing knowledges are out there, and being able to show those and side with one or another, so tentatively putting your own argument out there, in other words sort of entering a conversation that’s been going on for some time. So we asked students to… with their topics… to paraphrase the material that they understood, but that we gave them the structure of an argument, through a technique that’s come out of the University of Illinois called ‘Templating’. And that’s when you provide the signalling language for students and they’re able to make sense of how texts work structurally, particularly when there are more than one voice in the text. So you can see that the reading material was paraphrased then inserted at the end of those templates and from that students were able to structure an entire argument. And we found also that, I mean, even though this was an introduction to argument, that they were able to move out of these templates fairly easily once they became familiar with the discourse or elements of the - of the template and of the mode of the engagement, anyway. And also, the one thing that they found that was… it was… it was quite empowering and it really maximised this sense of diversity> I guess the way we see it is that even though these students are coming from very diverse elements there, sort of, you don’t know who’s in your class sometimes, and I’m sure many of you experience this -that multi ability in the classroom - you just don’t know what’s there. But if you can have some sort of unifying idea or concept of how… where you are bringing students… we just found that was a far better way to engage and also develop any number of sorts of skills that were out there and avoid perhaps some of the pitfalls that Angela has talked about that students were falling in beforehand. We, it really helped us and I guess we’re here to discuss it with you, and listen to your ideas as well. Speaker 1: Good; we’re going to open it up to questions now. But I guess just in summary it’s just… the… the simple message is it’s really about making language and discourse explicit - I mean, that’s what it is. And making those features really explicit to make them more accessible to students who might have some barriers around finding that accessible, I mean that’s the, that’s the core sort of practice or technique, I guess. I think that’s all we really needed to say. We’ve got some references there if you want it… but yeah. just… if people have questions, I don’t know how long we’ve got. Speaker 2: We haven’t got very long. 10 Speaker 1: About 3 minutes, ok, yes, there’s a big one, a keen one Question 1: (Inaudible 38:51 – 38:57) perhaps, would you be willing to come and run through this workshop, or this session in schools at all? Speaker 1: I, well… yeah. Speaker 2: We haven’t got it at workshop stage but. Speaker 1: But we could. Question 1: But your message is very powerful for particularly secondary schools and schools that I am dealing with. Speaker 2: That’s certainly something that we have talked about and that we would really love to do. Question 1: Ok, I will come and see you. Speaker 1: Yes. Speaker 2: Yes, come and see us. Speaker 1: Any other questions? Sorry we haven’t left you much time… we lost track of it a bit, yep. Question 2: Although it’s not at workshop stage, do you have materials or something along those lines that could be made available to secondary teachers? Speaker 1: We’ve got two venues at the moment, but it’s something that we could develop and expand, we’ve actually, we’re publishing in, in the, what’s it called? Speaker 2: The International Journal of Educational Research. Speaker 1: So, and that, and that gives a bit more of the theoretical and some of the practical components. We’re also… we do have curriculum material that we use to sort of sustain it. Speaker 2: We have, we actually have quite a large bound copy of the teacher reflection for this program, that’s being contributed mainly by the language teachers but also by the sociology teachers. It’s, it’s really just a reflection on what happened in the class and how students responded. Hints, tips’ all of those sorts of things and it’s, although it’s sort of semi bound, it needs a little bit of work but it’s good to know that it could be something that’s useful. Speaker 1: That’s useful, and I guess it’s something that we would be very open to exploring, because we actually believe that, that the, approach has a lot of application across a range of other sort of levels. So we would be very happy to create and explore that in more detail. We just applied it to our group last year and… but there has been a lot of interest in, in the approach, so that’s why we have sort of tried to get it out there. But certainly we would be very happy to work with you and also with the School of Education with 11 the previous speakers too, about how we might sort of apply that in school settings or support you or work with you to sort of tease out the application, but yeah, happy to present and explore it more fully. Yes. Question 3: I just finished year 12 last year and we were given templates to write with but the examiners, like, they wanted to see different, like, they didn’t want to see those templates, so there’s like a fine line, I think. Speaker 2: Yeah, no, you’re right -there is, I think there, there might, there’s, there are some differences between writing in VCE and writing through the academic environment, but you’re right and I think this is part of… once you go beyond the templates and you become the master of sort of these very structured things, that’s when you can truly say that, you know, you feel comfortable with being in that environment. And I am sure I think that’s probably what the examiners were, were really looking for, but once you go past that structured sort of thing that you really become master of what you are doing and saying and writing. Speaker 1: That’s a very good point. The templates are a vehicle, they’re not the end, that’s the intention, so you are actually using the templating and also the lots of practice and, and lots of exploration with writing and building sort of some, some bridges, I guess, to actually get to an end point where you actually become a more confident member of the discourse. And that’s why we did things like, like that lovely example of “if the writer was in the room”, so actually putting students on an equal footing almost with that, with that discourse community instead of seeing them as totally sort of untouchable, unreachable, but it’s a good point. Speaker 2: Thank you. Speaker 1: I think we need to let you go. Speaker 2: Yeah. Speaker 1: Is that right? Speaker 2: Thank you very much everybody. Speaker 1: Thank you for paying attention. Speaker 2: Thanks. End of presentation. For more information about the topics discussed in this podcast, please visit the Department for Education and Early Childhood Development’s website education.vic.gov.au. 12