Character In Epistemology

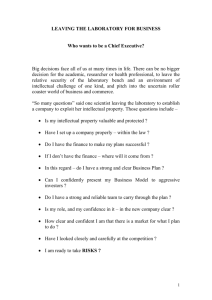

advertisement