Texas Architecture - Baylor University

advertisement

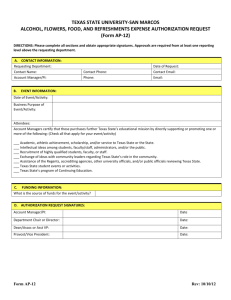

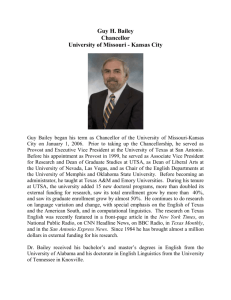

Treasures of the Texas Collection Texas Architecture The Texas Collection is well-known for its resources in the political, economic, and social history of Waco, Central Texas, and of Texas as a whole. A less well-known strength of the collection is the wide array of materials relating to the history of architecture and the built environment of the state. Hi! I’m your host, Robert Darden. Welcome to Treasures of the Texas Collection. In addition to being a student of museums in the United States and further afield, Dr. Kenneth Hafertepe, chair of the department of Museum Studies at Baylor University, is also an architectural historian. He has written about such prominent Texas buildings as the French Legation and the Governor’s Mansion in Austin; Ashton Villa, an early Victorian mansion in Galveston; and the Spanish Governor’s Palace and the homes of Sam and Mary Maverick in San Antonio. Ken, how is studying Texas buildings different from studying other parts of Texas history? The biggest difference is that to most people, buildings seem to be mute. Except for a few important public buildings or churches, the name of the original 1 owner or the designer or builders is rarely carved or painted onto the structure. You can find out something about them from the county real estate records and tax records, and less often from newspapers or books or letter or diaries, but too often we don’t find as much information as we’d like. But the biggest surprise to most students is that buildings really aren’t mute; actually, buildings can talk. The trick is that they speak a different language than most people are familiar with. It’s a language of materials – wood, brick, or stone. It’s a language of structure, from the wooden framing of a shotgun house to the steel frame of a skyscraper like the ALICO building in Waco. And it is a language of ornament – from Greek columns on the Earle-Harrison house to stained glass windows in the First Baptist Church. People might also be surprised to know that buildings have families: other buildings built at the same time or in the same region or by the same architect, buildings which are like brothers or sisters or cousins, but also ancestors that were earlier examples of a particular building type or style. The more familiar you are with the larger history of architecture, and the more you know of the language, the more a local building will tell you! When did architects first come to Texas? Pretty early, I’d guess. 2 To the degree that every person was their own architect, the first architects in Texas were the Native men who made grass houses or tanned buffalo hides for a teepee, or, out west around El Paso, the women who shaped adobe blocks and built adobe walls. A whole new type of architect was the Franciscan missionary, who was from Mexican cities like Queretaro, and was familiar at least with the local example of churches in the Spanish baroque tradition. They came to Texas and with the help of Native workers built the missions around San Antonio and El Paso, which are very important part of the architectural legacy of this state. Anglo-American carpenters and masons began to come in the 1830s and 1840s There were no schools of architecture back then, and so anyone who was willing to build a house or a church or a courthouse could call himself an architect. Abner Cook, the master builder responsible for the Texas Governor’s Mansion, called himself a mechanic in the 1850 US Census – that is, someone familiar with many mechanical crafts and trades – but in the 1860 Census he called himself an architect. But after the Civil War, a new breed of architect came to Texas, men with practical building experience but often with academic training in architecture as well. When these people moved from more settled areas on the East Coast to frontier Texas, what did they think of the buildings here? 3 Lucadia Pease and her husband, attorney and future Texas Governor Elisha Marshall Pease, who were both natives of Connecticut, found that Texas really was a whole ‘nother country. Mrs. Pease was struck by the newness, indeed the rawness of Brazoria when they moved there in 1851. Here’s a quote from Lucadia Pease from that first year: “All the houses here are small, and walls ceiled (sic) or badly plastered without papering – but in all these shabby houses they have much costly furniture – Sofas, marble slab tables, bereaux, and washstands, shade lamps & some handsome window curtains, with bare floors, tho’ some have matting.” Mrs. Pease also was not used to the Texas climate, and when she and Marshall were planning to build a new house, they had to try to take into account both the Texas heat and the wintry “blue northers,” which could change the weather from balmy to frigid in a matter of hours. She wrote to one of her sisters: “Our new house is still a “Castle in the air” and we find it very difficult to draw a plan adapted to the Climate, i.e. rooms all South to catch the Gulf breeze, without which we could not endure the warm weather, and to avoid the northers which are here so much dreaded… The square house is exploded as the two north rooms would be useless, but the Gallery’s or Piazza’s are here quite indispensible as we live almost entirely on them through the day and at Mrs. Whartons in 4 summer they put out their beds, and sleep at night – and of course we must have them.” . For Mrs. Pease the most important room in the house was actually outside – the gallery or porch. Its roof gave you shade and protected you from the rain, but allowed whatever breeze there was to cool you off! I imagine that Northern European visitors had an even harder time adapting… That was definitely true of Alphonse Dubois, who was the French charge d’affaires to the Republic of Texas. Dubois was actually a commoner, but decided he could put one over on the Texans by declaring himself to be the Compt de Saligny! His house, known as the French Legation, is the oldest remaining house in Austin, built in 1840-41. The only houses available for rent in Austin in 1840 were log cabins, and loose pigs kept getting into the diplomat’s papers and linens! So Dubois decided to build his own house on a hill east of town. It was only four rooms arranged around a central hallway, but it had a large parlor and dining room, so that Dubois could wine and dine officials of the Republic of Texas. However, the Legation was completed only shortly before Dubois’ abrupt departure from 5 Austin, and he did most if not all of his entertaining in his rented log cabin on Sixth Street. Isaac van Zandt, who served in the Congress of the Republic of Texas representing Marshall, attended one of those fabulous dinner parties, and wrote about it in a letter home to his wife: “It was the most brilliant affair I ever saw, the most massive plate of silver and gold, the finest glass, and everything exceeded anything I ever saw. We sat at the table four hours – I was wearied to death but had to stand it with the company. We had plates changed about fifteen times.” The Van Zandt letters show that a dining room can be a dining room, but it can also be a diplomatic tool. When E.M. Pease was elected governor, there was no mansion in Austin yet. He and Lucadia were forced to rent, and they could not even find a vacant house, and instead boarded with the family of former Austin mayor Thomas William Ward. Here’s another snippet of a letter from Lucadia: “Marshall had found it impossible to hire a comfortable house, and had consequently engaged our board with a very pleasant family, Col. Ward’s formerly from New Hampshire. They have a very good house for Texas and we are altogether very well situated.” 6 Lucadia could not resist that little dig comparing Texas to New England – the Ward house was a very good house - for Texas! When her husband decided to build a Governor’s Mansion, there were no architects in Austin. He and the committee hired the leading master builder. Those are fascinating descriptions of life and architecture in early Texas towns, Ken. But do we know as much about life in the country, life in farmhouses and in the plantations? It is harder to find detailed descriptions of plantations, especially from the antebellum era. Fortunately, at the Texas Collection you can find a remarkable description of an antebellum plantation on the Brazos River here in McLennan County. It is in an advertisement placed by W.W. Downs in a Waco newspaper, the Weekly Examiner and Patron, in the fall of 1877. It reads: “Fine Brazos Plantation - FOR SALE OR LEASE On account of the infirmities of old age I offer my Brazos river plantation for lease or sale. The tract comprises 1750 acres about 1100 of which is Brazos bottom – the finest lands in Texas – and the balance 650 acres choice Post Oak and Prairie. Of the bottom lands there are 530 acres under fence and in a good state of cultivation with Steam Gin and Mill, Blacksmith and wood shops, tenant houses, 7 barns, lots and other improvements, including a country store house at one of the best stands for selling goods in the county. The place is well stocked with horses and mules, hogs, cattle and corn, all offered with the place. This is known as one of the richest and prettiest, and in all respects most desirable plantations in Texas… It is offered at a bargain to responsible parties on small payments of cash. Address me at Waco, or apply on premises, seven miles southeast of the city.” That sounds pretty good – assuming it was all true! What is so striking is the way in which a plantation was a little town of its own. A plantation was not just one big house; arranged around it would be mills and shops and barns and even a country store. And did you notice what Downs referred to as tenant houses? That was where free blacks who worked the land were living; but before the Civil War those “tenant houses” would have been called the “slave quarters.” At the time of the 1860 census Downs reported that he owned five house slaves, who lived in two houses, and 72 field slaves, who lived in 12 houses. Downs was the biggest slave owner in McLennan County; second place went to Mrs. Eliza Earle, widow of Dr. Bayliss Wood Earle, who owned 61. This census 8 information also tells us something about the different lives of house slaves and field slaves. The house slaves lived in a small house with two or three people, whereas the houses for field slaves averaged six people per house. It must have been mighty crowded! Did African-Americans also have a role in the building trades? In the antebellum era, many enslaved African-Americas were skilled carpenters or brick masons. Many slaves had to build and furnish their own quarters; while other enslaved craftsmen were rented out to big construction projects like the 1852 State Capitol. Because Abner Cook owned ten slaves in the 1850s, it seems highly likely that enslaved craftsmen helped build the Governor’s Mansion. And the brick walls of Ashton Villa on Broadway in Galveston were built by Aleck, an enslaved craftsman who was purchased by James Moreau Brown just for that purpose. Aleck and Mr. Brown are both long gone, but the house they built still stands in Galveston. According to the Memoirs of Mary Adams Maverick: Turn Your Eyes Toward Texas, Sam Maverick and his wife Mary Adams Maverick built a house on the northwest corner of the Alamo Plaza in 1850. Or I should say, they had a German contractor build it for them. 9 In 1847 Sam wrote to a U.S. Army officer in San Antonio, explaining that “I have a desire to reside on this particular spot, a foolish prejudice no doubt as I was almost a solitary escape[e] from the Alamo massacre having been sent by those unfortunate men” to the independence convention. If Sam and Mary had their bedchamber in the south room upstairs, they may well have had a remarkable view of the old mission. . I guess after the Civil War, Victorian architecture was the last word, right? For sure. The wonderful Victorian houses of Galveston, like the Bishop’s Palace, were designed by the Irish immigrant architect Nicholas Clayton. And many Victorian houses in San Antonio, especially in the King William neighborhood south of downtown, were designed by the English émigré Alfred Giles. The book Inside Texas: Culture, Identity, and Houses, by Cynthia Brandimarte allows us a peek inside many Victorian houses. She scoured every archive in the state and farther afield looking for photographs of Texas interiors taken before 1920. The results are amazing, and it includes multiple photos taken inside, including the Gregor McGregor house in Waco. The house is gone now – it was on Columbus Avenue at Eighth – where the Masonic Temple is, but the house 10 was photographed in 1896, at the time of a wedding, so we know what it looked like inside early on. The parlor of the McGregor House was richly decorated with wallpaper and carpets and elaborate furniture. Prominently featured on the wall was an engraving of Robert E. Lee on his horse Traveller. The image of Lee, the commander of the Confederate Army in the Civil War, was a powerful one for many Texans who fought for the Confederacy. What a treasure! Are there notable things about Texas architecture of more recent times? Yes, indeed. There have been a couple of books on John Staub, the architect of many of the fine houses in the early Houston suburb River Oaks. He played a role in Houston similar to what Birch Easterwood did in Castle Heights and Sanger Heights in Waco. They both specialized in period houses – different types of American colonial, Tudor Revival, and Spanish Colonial Revival. Staub also experimented with house designs that recalled the style of pioneer Texas houses. In the Texas Collection there is a great bit of evidence in the old Waco News-Tribune in February 1923. The paper selected Birch D. Easterwood, the architect who had recently designed Brooks Hall on the Baylor campus, to design a model home to be built on Colcord between 30th and 31st. This was in the Highland 11 Addition, and readers of a two-page spread were encouraged to “drive out in beautiful Highland addition and visit the site where the ‘model’ home is being built.” It has sketches of the house and a floor plan – great documentation. The News-Tribune stated that Easterwood “was selected because of his past and present achievements and because of his many satisfied clients.” The Texas Collection also has a great Waco Chamber of Commerce publication from 1926 showing all the fine new homes being built in Waco. In the 1930s Texans built a lot of great Art Deco architecture. That was a style that tried to be very consciously modern and to catch the jazzy spirit of the age. The buildings in Fair Park in Dallas were enlarged and remodeled for the Centennial State Fair in 1936. The Hall of State is an especially wonderful example of the style. Fort Worth got into the act with the Will Rogers Coliseum, and Houston with the San Jacinto Monument. And to spread the wealth around a bit, the State of Texas built museums in Austin, Huntsville, Alpine, and Canyon. And do Texans have much to brag about in even more recent architecture? I think two things are especially striking. Texas has become a laboratory for skyscraper design, and in the last fifty years Texans have built an incredible array of museums. In the 1960s and 1970s Philip Johnson designed the Amon Carter in Fort Worth and the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi, Ludwig Mies 12 van der Rohe designing the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and Louis Kahn designed the Kimbell. More recently, new buildings have gone up in Houston by the Spanish architect Rafael Moneo; in Fort Worth the new Museum of Science and History by the Mexican firm of Legoretta and Legoretta. And the Italian architect Renzo Piano has designed the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas and an additional building for the Kimball in Fort Worth. Unfortunately, I’m guessing that a forward-looking state like Texas has demolished an historic building or two. The late Willard Robinson, who taught architectural history for many years at Texas Tech, published a book called Gone from Texas. The title was riffing on the old story that people leaving Tennessee or other states would carve GTT on their door, which was a shorthand for “Gone to Texas.” Robinson’s Gone from Texas consisted entirely of wonderful buildings of the nineteenth and early twentieth century that have been destroyed or so drastically remodeled as to be no longer recognizable. Dallas Re-discovered is another wonderful book that always makes me cry every time I look at it. That’s because I was born in Dallas, and the book documents the wonderful Victorian homes, businesses, and other buildings of Big D, almost all of which have been destroyed. 13 What a shame. Still, on the other hand, Texans have been known to take care of their treasures, too. At least some of them. Yes. The first historic preservation project in Texas was the Alamo. As you know, the Alamo was originally Mission San Antonio de Valero, but it was preserved by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas because it was the scene of the Siege of the Alamo during the Texas Revolution in 1836. The two leading members of the DRT, Clara Sevier Driscoll and Adina De Zavala, had a falling out over whether to preserve the remains of the building next to the Alamo chapel, but the DRT has persevered and still has responsibility of caring for the Alamo today. And did saving the Alamo give rise to other preservation projects? Yes. On March 21, 1915, Miss Adina De Zavala published an article in the San Antonio Express with the title, “Governor’s Palace with Imperial Coat of Arms Tells of the Spanish Rule.” Miss Adina claimed that it was the Spanish Governor’s Palace, but in recent years writers have acknowledged that was actually the house of the presidio commander. On a 1766 map, it is simply called the “Casa del Capitan.” The publication of this article inaugurated a thirteen-year campaign that culminated with the restoration and reconstruction of one of the oldest buildings in 14 San Antonio. The intensive restoration (and reconstruction) was carried out between June 1929 and July 1930 by architect Harvey P. Smith. In the 1930, Smith went on to be the restoration architect at the other four missions in San Antonio. I hear that you have spent “just a few” hours in the Texas Collection researching the architecture of German Texans. Yes, I’ve been working for more than six years on a book that will study German immigrants to Texas from the 1830s up until the 1910s; their rock houses and churches, but also their furniture and artwork and even their gravestones. A lot of great work was done by the cultural geographer Terry G. Jordan in the 1960s and 1970s, but it’s time for a new look that goes more deeply into the subject. Any new books of note on Texas architecture to watch for? It looks like we will soon see the first full-length study of J. Riely Gordon. It is really a great story, Gordon came from Virginia and in less than twenty years designed county courthouses all over Texas, including LaGrange, San Antonio, Waxahachie, Decatur, Sulphur Springs, Marshall, and the McLennan County Courthouse in Waco. 15 Wonderful! Thanks for reminding us of Texas’ architectural legacy, Ken – and the people behind it! The Texas Collection on the Baylor campus has one of the country’s largest collections of documents, books, maps, letters, photographs, memoirs, diaries, magazine and newspaper articles, minutes and official records – just about anything you can imagine. For more information about the Texas Collection on the Baylor University campus, go to http://www.baylor.edu/lib/texas I’m Robert Darden, Associate Professor of Journalism, PR & New Media at Baylor University. Thanks for joining us on Treasures of the Texas Collection. Treasures of the Texas Collection has been made possible by generous grants from The Wardlaw Fellowship Fund for Texas Studies and by the FergusonClark Endowment Fund. This has been a production of KWBU 103.3 FM – public radio for Central Texas. 16