Week 2

advertisement

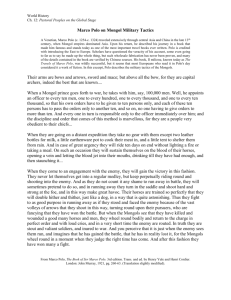

ENGL6080 Travel Writing and Culture Notes for Week 2 Writing the East: Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville 1. Marco Polo (1254 - 1324) Author and Book Marco Polo is the most famous of medieval European travelers. His account of China in his only written work, known in English as The Travels, inspired other Europeans, including Columbus, to seek the ‘Cathay’ he so wonderfully describes. Yet he struggled to persuade his contemporaries of the book’s authenticity, and more recently, scholars have also questioned some of the content, especially its historical accounts. There is no firm evidence to suggest that The Travels is a first-hand account of Polo's travels. No convincing record of Polo’s presence in China has been found, and Chinese history does not support the claim in his book that he spent 17 years there as envoy of the Kublai Khan. This does not mean he did not go to China, but there is some evidence he might have exaggerated some of his claims. Frances Wood has pointed out that much of Polo's vocabulary is Persian rather than Chinese, indicating that he might have based at least some of his account on Persian sources. Others have noted that he omits significant aspects of Chinese life and culture which does seem remarkably remiss of him. There is no mention of the Great Wall for instance, or the custom of foot-binding and tea ceermonies [which were well established by the 13th century]. (See Frances Wood, Did Marco Polo Go to China). But claims and counter claims are difficult to prove. The idea of authorship in medieval times was more fluid, and always more collaborative. There is no original manuscript and the oldest copies, in medieval French and Latin, have been copied and edited many times. About Polo himself, we know little, but he was a real character, and records still exist of his birth and his final will. It seems he left little of great value to his family, and he may well have spent his remaining years an embittered man, trying to publish his book. His fame did not spread until after his death, when a version was produced by Ramusio containing the Prologue which he probably wrote himself. According to this, Polo had dictated his book a well-known writer of romances, Rusticello of Pisa, while they were both confined in prison in Genoa. This adds another twist to the eventful production of the text. First Travel Book to Present a Realistic and Visitable East Whatever the doubts about authorship and authenticity, Polo's Travels undoubtedly presents realistic details of a China never before written about so extensively in a European language. Whether we are reading the experiences of Polo himself, or a skillfully crafted accumulation of second-hand experiences, is perhaps not the point. As literature, The Travels is still an important work, not least because it discloses European attitudes to the East in the medieval period and because it was subsequently a major shaping force on the European imagination. If it was subsequently amended and redrafted to get the approval of the Church (which has been suggested), then this tells us more about the European imagination and worldview. To a modern eye, The Travels might seem tedious and repetitive. Repetition was a literary mode at the time, so this is not surprising, but it also gives the text a greater sense of realism – in other words, travel does often produce repetition rather than constant variety. On this basis, Polo was the first to narrate a mundane and largely realistic geographical East, with formulaic phrases designed to emphasise the frequency of particular features. He is also careful not to dispel too many comforting illusions long held by European Christians about the East, such as the myth of the Christian king, Prester John. But The Travels radically changes the mapping of the East for Europeans who had previously only seen the East through the heavily symbolic cartography of mappae mundi. Polo produces a traceable ‘map’ of the East, turning into a place to be visited, rather than simply written about and imagined. In the process, he also contested the Euro-centric worldview, by introducing a ‘two-centred world’. He draws comparison between these two centres, unsettling western supremacy, but also inciting European exploration in search of the riches of China. Polo's Travels was the first European book to offer practical information on places, routes and people. Where it tries to fill in the history of the East, it is often inaccurate, and there are some worrying 'slips' in his history of the Tartar Wars. But such 'slips' do not take away from the book's realism. Polo's narrative gives the sense of places which are visitable rather than present only as the material for fabulous and miraculous stories. Polo's Travels is the first book to begin to impose a 'real' East on the mythical and fabulous East that preceded it in the European imagination. The Merchant's Eye The point of view in The Travels is, for the most part, clearly that of a merchant. This can be seen from the language used and from the detail that relates to commercial interests, such as products, prices, means of transport, currency, and laws and customs that the merchant may need to be aware of. In the most-cited passages, there is greed in that merchant's eye as it scans the wealth of products and the superiority of Chinese civilisation. The one thing Polo does not mention, is what China might want from Europe - this was always a bit of a stumbling block in East-West trade, and one of the factors leading to the Opium Wars. As Polo (and others) maintain, the Kublai Khan was always willing to entertain foreigners and listen to their ideas and inventions, but there does not seem to have been much in terms of products that China wanted or needed from the West at this time. Realism or Romance? Given that The Travels was transcribed by Rusticello, a man famous for writing Arthurian legends about knights, castles, dragons and quests for the holy grail, we might wonder if this flavoured the text and compromised its realism. The passage that describes Polo's first meeting with the Kublai Khan, for example, is very similar to a passage in one of Rusticello's romances. There is an interesting traffic here between European fantasy and Chinese reality which goes some way to explaining how the East was cast in an exotic light by Europeans. An Exotic East By presenting such a positive view of the East (especially China), Polo contributes to a new (in medieval times) European attitude to the East. It was always exotic in the sense of being different, strange, or unnatural, but in Polo's Travels, the East becomes highly desirable to Europe. This new casting of the East also contains a degree of feminisation: associated with the beautiful, the perfumed and the sensuous. In this there is also an implication and veiled criticism that although rich, the East may be morally weak, and pleasure-seeking. The Text The book first appeared in Europe in the early 14th century. There are a number of manuscripts in different languages, but it is likely that the original was written in Medieval French by Rusticello (French being the accepted language of romance). Between Polo's actual travels and the modern edition of his Travels there may be many alterations, embellishments, omissions and mistakes, introduced by copying, translation and editors wishing to change the text for some reason. Specifically, it was necessary for Polo to have the book accepted by the Christian establishment which censored manuscripts diverging from the Scriptures in either way. In this atmosphere of Christian fundamentalism, it would be naive to assume the text we read today in translation is a verbatim account of what he told Rusticello, even if this was what he actually saw, and even if this is what Rusticello wrote. The book describes an epic journey of over twenty years duration (1271 - 1295) overland from Western Europe, across the Middle East, central Europe and Asia to China, and back again to Venice by sea (although the return journey is only described briefly in the Prologue which was probably added much later by an editor) The book is set out as follows: Prologue 1. The Middle East 2. The Road to Cathay 3. Kublai Khan 4. From Peking to Bengal 5. From Peking to Amoy 6. From China to India 7. India 8. The Arabian Sea 9. The Northern Regions and Tartar Wars The Prologue tells the story of an earlier journey made by Polo's father and uncle. According to this story, the elder Polo's had already been to China, met the Kublai Khan and returned to Italy with the intention of fulfilling the emperor’s request to bring 200 educated Christian men, a blessing from the Pope and oil from the lamp at Jerusalem to his court at Khan-Balik (Peking). After some delay, the Polo's eventually returned to China with the young Marco Polo, who at the age of seventeen, was presented to the Khan. So the story goes, Kublai Khan was so impressed with the young Marco that he sent him as a special envoy through his empire to gather information. Discussion points for Polo’s The Travels. Consider some of the following features of the text and discuss their effects and their effectiveness in travel writing: 1. The mode of narration is revelation (art of revealing) rather than reported action - use of 'continuous present tense' e.g. "In this place, there are these wonderful things", rather than "When I visited this place I saw these things..." 2. Presentation of 'wonders and marvels' - see emphasis on gold, spices, silk etc. 3. 'Armchair Travel' - text pulls us along a journey - address to reader as traveller e.g. "Now let us move on to the next place ..." 4. Narrative time is the time of telling not the time of travelling e.g. "I told you this, now I am telling you this, and afterwards I will tell you about this" 5. Voice of narrator is more prominent than that of the traveler. 6. 'The traveller' as a detached figure - an everyman - note that the impersonal 'traveller' is usually, but not always the subject. 7. Exaggeration (hyperbole) and superlatives (Polo was nicknamed Il Milione) 8. The language and point of view of a merchant 9. Repetition 10. Geographical completeness in the narrative 11. A Western male gaze? Kinsai as feminine, exotic and desirable to male travellers. 2. "Sir John Mandeville" Man, Persona and Book Mandeville claims to be an English knight of the 14th century, but we know nothing of this author outside the book he left. The 'Mandeville persona' who narrates Mandeville's Travels, introduces himself as an aging English knight returning home after travelling extensively in Arabia, Central Asia, North Africa, and the Far East. But this is a little like the framing device found in fictions like Robinson Crusoe – it does not reflect reality so much as produce the reality effect. The book was written about 1357, and was destined to become the most popular book of the Middle Ages. It was translated into most European languages and was used by explorers such as Columbus, as well as medieval cartographers. While contemporary interest was based on the book’s dual role of entertainment (the revelation and confirmation of wonders) and information (on astronomy, science, religion and philology), its interest today rests on its subtle representations of European attitudes to ‘otherness’ – specifically, Christian attitudes to Islam and other religions as a critical reflection on Christendom and the (corrupt) institution of the Church. The Poetics of Plagiarism The book has multiple sources and it is often said that Mandeville or the 'Mandevilleauthor' (to be pedantic) never travelled further than the libraries of Europe, relying on second-hand accounts from others. Some sections are clearly plagiarised from twenty or so authenticated sources, including Oderic of Pordenone's Itinerarius, the letters of John of Plano Carpini, and Alexander's letter to Aristotle. Mandeville was undoubtedly a scholar who had studied widely, and possibly travelled to the Middle East during the Crusades, or on pilgrimage, but probably never visited Asia. From a modern perspective, Mandeville might be called a plagiarist or fabulist, but in the context of medieval literature, his ‘crime’ is much less serious. It was common in his time to re-use source material and to juxtapose familiar texts with commentary – this was a mode followed by no less than Chaucer, a contemporary, and later Shakespeare. Both were experts in what Chaucer called, ‘producing new corn from old fields’. What Mandeville’s recycling reveals is the particular ‘spin’ he puts on already-circulating travellers’ tales. He provides us with a compendium of diverse medieval texts (and some of his own original material), re-presented through the filter of a distinctive liberal and pluralist consciousness, not unlike what we now perceive as a ‘postmodern consciousness’. One of his main devices is to introduce fictional dialogues to provide ‘reverse othering’. Here the travellee passes comment on the traveller and by extension the society he represents. Such a device is later found in more sophisticated modern travel writing, which is more conscious of the need to express the travellee’s point of view. More straightforwardly, he embellishes the accounts of others with humour and irony, frequently making political and philosophical points. Reflection, Irony and Satire Mandeville reveals little about the East that was not already documented. Where Polo's text is enthusiastic in promoting the East and promoting Polo himself as the hero of his travels, Mandeville is self-deprecating and reflective. Mandeville's Travels may on the surface look like poorly stitched together work using the words of others, but scholars have recently found a subtle and intelligent mind at work here, one which uses travel writing about the East to reflect on the errant ways of the West. It is very common in later fictional travel writing to do this - see for example Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels and Thomas More's Utopia, where fictional places are used to explore alternative societies or to satirise present society. A Rambling and Digressive Traveller Unlike Polo, Mandeville is not a heroic traveller/narrator. He is not master of all he surveys nor master of all he tells. He often confesses to omitting details, and seems intent on not getting bogged down in long descriptive passages. There is always too much to tell, and he turns his failure to organise and structure his material into a representative mode – high on anecdote and tall tales, but short on facts and synthesis. Mandeville's Travels has none of the careful mapping we get in Polo. For example, "From this country men go through the Great Sea Ocean by way of many isles and different countries, which would be tedious to relate." (127). Mandeville also breaks off abruptly and introduces extraneous material through digression. Given the relative popularity of Mandeville’s book, this might tell us something about European tastes at the time. Realism and Fantasy Whereas Polo's mode is essentially realistic, Mandeville frequently wanders off into the fantastic (e.g. the descriptions of assorted monsters). He deliberately doesn't signal the switch from realistic to fantastic description, leaving it for his audience to distinguish the real from the unreal, and also experience the delight of sometimes quite random juxtaposition. This may seem odd to a modern audience accustomed to fact and fiction being clearly divided (at least until postmodernism) but for a medieval audience, it was very common to have different kinds of writing and different modes of expression bound together in the same book. Before modern science, 'natural history' (see Pliny) was in the realm of the fabulous, and medieval audiences treated scientific findings as wonders and marvels, hardly differentiated from the miracles of the Scriptures. Mandeville and the Church Polo, the merchant traveller, makes only formulaic references to Christianity (consider this in Polo), but Mandeville expresses serious concerns about the state of the Christian Church in the West. In his Prologue to the Travels he writes about the corruption of the Church, and the unworthiness of Christians. This reaches a high point when he includes a reported dialogue with the Sultan of Egypt, in which the Sultan (a Saracen (Muslim)) openly criticises the Christian Church for being corrupt and Christians who murder each other and would sell their daughters. Significantly, Mandeville does not offer any defence, but he does reaffirm his own faith in Christianity. His concern is that other faiths such as Islam are more strictly adhered to and therefore superior in that respect. Travel Abroad as a Mirror to Home Polo rarely compares the East with the West, except to tell us how much more wonderful and splendid are the cities of China. Mandeville constantly makes comparisons between East and West, seeking likenesses as well as differences. Mandeville's East is not just a land of opportunity and a potential competitor (as it was for Polo and later the explorers and colonialists of Europe); his East contains alternatives and improvements to the West, and he is especially concerned with how the East has lessons to teach the West with respect to cultural, moral and religious matters and social organisation. Mandeville's text seeks knowledge about the East not to dominate it, but to not learn through comparison and self-reflection how things might be improved at home. Mandeville's partreal, part-fictional East becomes a 'mirror' to the West. In the East, the West sees reflected its own values, customs and practices. Sometimes this reflection is postive: i.e. we see the same in the East as in the West; sometimes the reflection is negative: i.e. we see difference (maybe better, maybe not) in the East. We can say then that the East is used as a 'negative mirror' . Dialogue as Cultural Exchange Unlike Polo, Mandeville includes a number of significant dialogues in his Travels in which cultural exchange takes place. These are subtle examples of mirroring and are almost certainly fictional. The purpose of these dialogues is generally to exchange ideas on Eastern and Western values, morals and customs, especially with respect to different religious faiths. See for example how the Buddhist faith is contrasted with Western Christian ideas - he does not force his own (Christian) values on the Buddhist monk, or argue with him. He even seems to accept the implicit criticism of Christianity here with respect to the system of charity. One World, One Nature, One God Mandeville's comments on East/West relations suggest the idea of mutual understanding, and bring East and West together in a 'One Nature/One World' view. This is remarkable in the Medieval period when the East was about as remote as Jupiter is to us today. Hitherto, except in the accounts of Polo and Christian missionaries, the East was always essentially different and conditioned by its exotic difference from the West. Exotically different and sometimes monstrously different, Western thinking for hundreds of years had considered the East as 'other', populated by monsters, plants and strange human forms that belonged to a different system of Nature. The long passage about circumnavigation (pp. 128-30) in Mandeville's Travels, although ostensibly offering mathematical and astronomical proof of the size and shape of the earth (quite accurately in fact), is at the same time suggesting a planetary consciousness – it brings the East (and the South – the Antipodes or opposite feet) within the same compass as Europe and the Holy Lands, centred on the Mediterranean. For Mandeville, there are multiple kinds of people, plants, animals and customs all over the world, and this gives great pleasure he says, but at a higher level, there is only One Nature, One World, and One God which operate as a unified creative force. Discussion points for Mandeville’s Travels (illustrate with at least one example from the text) 1. Contrast Mandeville’s style with Polo’s. 2. Assess Mandeville’s ‘literariness’ and consider the advantages/disadvantages of literary style in travel writing. 3. Does lying have a place in travel writing, and what exactly constitutes a ‘lie’ in this context? (consider the difference between veracity and verisimilitude) 4. What are the effects of juxtaposition (of different kinds of information)? 5. Find one of Mandeville’s ‘jokes’ and try to explain how it works and what its function might be in the text. Paul Smethurst 5. 9. 2012