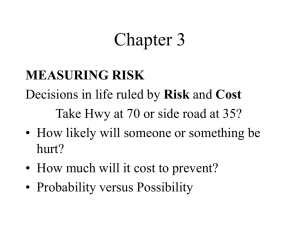

In late 19th century America, conditions were ripe for a new school

advertisement

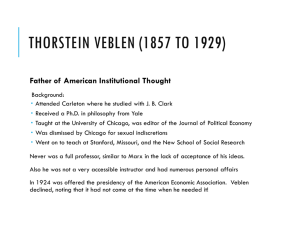

The American Institutional School and its Leading Proponents Amanda Ireland In late 19th century America, conditions were ripe for the emergence of a new school of economic thought. The abstract models of European classical and neo-classical economics had been crudely transplanted into a quite different cultural setting. “While the European capitalist was still caught in the shadow of a feudal past, the American money-maker basked in the sun – there were no inhibitions on his drive to power or in the enjoyment of his wealth.” (Heilbroner, 1999, p214). Various ultra conservative economists of the time were essentially “apologists” for the status quo of new industrial capitalism and its unchecked greed, bloody confrontation between labor and capitalists, and financial and agricultural crises (New School, 2008). However, the apologists’ often moralistic and theoretically loose orthodoxy was energetically attacked by a group of American economists who had been trained in the methods and philosophy of the German Historical school and who argued that “economic behavior and thus economic ‘laws’ were contingent upon their historical, social and institutional context” (ibid.). Much as Karl Marx used a historical materialist approach in his economic theories, Historical School economists such as Richard T Ely (1854-1943) responded to classical thinking with a controversial labor, socialist and empirical view, paving the way for a new heterodox school. The initial theoretical framework for Institutional thinking was provided by Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929), a secondgeneration Norwegian immigrant from the Minnesota frontier. Veblen developed an alternative theory of human development that offered rich new insights into economic behavior and a sharp critique of classical and neoclassical economics. In his collection of early essays: The Place of Science in Modern Civilization, Veblen argued that “the central ideas of the classical system did not reflect a search for truth and reality; rather they were and are a celebration of approved belief.” (Galbraith, 1991, p171). He posited that the rational, pleasure-maximizing economic man in classical economics was an artificial construct and that human motivation was far more diverse. Veblen outlined his theory in the extraordinary and hugely popular Theory of the Leisure Class in 1899. The book coined the terms “conspicuous consumption” and “conspicuous leisure” which described not only the behaviors of a “predatory, pecuniary class” but also the lower classes that sought to emulate them. (Veblen, 1899). Veblen regarded modern culture as little removed from the primitive, barbarous era. While Veblen was sociologically insightful in Leisure Class, the economic implications of his theories of human motivation served to disparage the concepts of utility and rational expectations. Along with status emulation, Veblen argued that three “psychological instincts” drove technological advance and transformed the nature of human society: a parental bent (general concern for future generations), idle curiosity and the instinct of workmanship. In The Theory of Business Enterprise (1904) Veblen further articulated the instinct of workmanship and proposed a hitherto unacknowledged dichotomy between industry and business; in which engineers’ concern with abundant production of useful commodities conflicted with the owners’ focus on profits. In economics, the students and followers of a great thinker often extend, refine and offer new applications for the original train of thought and in the case of Institutionalism, further development was provided by John Commons (1862-1945) and Wesley Mitchell (1874-1948). While Veblen had defined institutions rather loosely as “prevalent habits of thought”, Commons offered the more precise “collective action in control, liberation and expansion of individual action” (Commons, 1931, p1). Such collective action ranged from unorganized customs to organized going concerns such as the family, corporation, trade union and state. While Commons’ theoretical posture did not have great staying power, he left a significant legacy in the application of institutional thinking. Commons was a pioneer of labor economics, and is also regarded as the “spiritual father” of social security for his own and his students’ role in designing most of the progressive Wisconsin and New Deal social legislation of the 1930s (Arestis, Sawyer, 1992). Interestingly, historicist Richard Ely was a teacher and mentor to both Commons and Mitchell, and subsequently developed the University of Wisconsin as a breeding ground for a new generation of Institutionalists. Here it should also be noted that Ely was founder of the American Economic Association, which was initially dominated by Institutionalist thinkers. “Of the three American economists customarily regarded as the fathers of American Institutionalism, Mitchell would appear to have the most secure current reputation,“ (Arestis, Sawyer, 1992, p358). Mitchell was devoted to studying business cycles and insisted that the economy could be properly understood only if it were “examined and evaluated as part of the larger societal and cultural structure within which it is embedded, “ (ibid.) Mitchell’s profound contribution to modern economics was in founding the National Bureau of Economic Research. At this stage it is important to note that neoclassical thinking was in retreat while Institutional economics was enjoying its brief heyday. Neoclassical economists had promised a scientific explanation of economic phenomena, but their holy grail of marginal utility hypothesis was unobservable and unmeasureable, and seemed to be descending into “quackery” (New School, 2008). As Mitchell noted in his presidential address to the American Statistical Association after World War II: “While I think that the development of the social sciences offers more hope for solving our social problems than any other line of endeavor, I do not claim that these sciences in their present state are very serviceable. They are immature, speculative, filled with controversies,” (Fabricant, 1984, p9). If the abstract mathematics of the neoclassicists was not yet fruitful and predictive, the Institutionalists indisputably stepped into the breach. Mitchell, for his part, insisted that “good economic theory must be empirically grounded” (Arestis 1992, p360) and from its inception, the Bureau provided the empirical detail “…so that theorists could proceed from reality to significant generalizations for testing.” (ibid.) Institutional thinking was largely eclipsed by the Keynesian revolution. The Great Depression opened up a chasm between economic orthodoxy and world events, which John Maynard Keynes filled with a new economic framework for the current, severe and persistent economic problems. Subsequently, the neoclassical synthesis, Paretian revival, Keynesian and postKeynesian economics were the order of the day. However, Institutionalism lived on for a time, although decidedly off the center stage of economics. Two modern economists, John Kenneth Galbraith and Robert Heilbroner, shared a talent for publishing popular economic literature, articulating new and reformulated institutional theories, and thus provided the most recent dissenting voices. Galbraith (1908-2006) revived the theories of Veblen in his most famous work The Affluent Society (1958): “The ostentation, waste, idleness and immorality of the rich were all purposeful: they were the advertisements of success in the pecuniary culture. Work, by contrast, was merely a caste mark of inferiority […] In the central tradition the worker was accorded the glory of honest toil. Veblen denied him even that.” (Galbraith, 1998, p46). Another Veblen idea, from Theory of the Business Enterprise (1904), was refined by Galbraith in The New Industrial State (1967), specifically that a “technostructure” of professional managers hold more power in large firms than owners or shareholders, undermining the classical economic conception of the business owner. Most importantly, Galbraith attacked the principle of consumer sovereignty central to classical economics: “As a society becomes increasingly affluent, wants are increasingly created by the process by which they are satisfied.” (ibid., p129). Galbraith argued that the power of production and advertising contributed to private affluence and public squalor. In American Capitalism (1952) Galbraith expounded a restraint on economic power that appeared to replace competition, the concept of countervailing power: “private economic power is held in check by the countervailing power of those who are subject to it.” (Galbraith, 2001, p5). Power was a favorite topic of Galbraith’s and a focus of his dissenting economics. As President of the American Economic Association he presented an essay, Power and the Useful Economist (1972) criticizing the economics profession for ignoring power and thus employing irrelevant theories. In conclusion, Institutional Economics attempted and sometimes succeeded in keeping economics real. When the analytical tools of the profession were struggling, Institutionalists ushered in an empirical tradition that now contributes to every branch of modern economic inquiry. When economic models of behavior appeared far-fetched, Institutionalists provided more meaningful insights by drawing on other social sciences. This school of thought may have had its day but Galbraith and Heilbroner offer timeless parting words: “Economics divides today as between classicists (the overwhelming number) and institutionalists, between those committed to the inevitable and constant equilibrium and those who, which much less claim to scientific precision, accept a world of evolution and continuing change,” (Galbraith, 1991, p129). For his part, Heilbroner called for a “reborn worldly philosophy”: “Economics alone will not guide a country that has no vital leadership, but leadership will lack for clear directions without the inspiration of an enlightened as well as an enlarged selfdefinition of economics,” (Heilbroner, 1999, p321). References Arestis, Philip, and Sawyer, Malcolm. (Eds.). (1992). Biographical Dictionary of Dissenting Economics. Aldershot, UK. Edward Elgar. Commons, John R., Institutional Economics, American Economic Review, Vol.21, 1931, pp.648-657. Fabricant, Solomon. Toward a Firmer Basis of Economic Policy: The Founding of the National Bureau of Economic Research. 1984. NBER Galbraith, John K. A History of Economics. Penguin, 1987.London, England. Veblen, Thorstein, The Theory of the Leisure Class, The Collected Works of Thorstein Veblen Vol. 1, 1994. Heilbroner, Robert L. The Worldly Philosophers. 1999. Touchstone, New York, NY History of Economic Thought