ASHE_knight - University of Southern California

advertisement

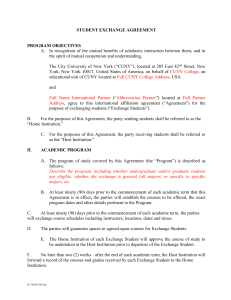

Negotiating their futures: Ethnographic research informing K-16 college policies and practices through urban youth’s eyes Michelle G. Knight Assistant Professor of Education Teachers College, Columbia University A paper prepared for the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Sacramento, California, November 21-24, 2002 1 [Thinking about college in 10th grade] brings more headaches ….Like which one [college] to choose. There’s a lot. Like I am trying to get a good score on the SAT. That is giving me a headache. And then, the Regents aren’t helping either. And then that’s it …and what they expect you to have to go [to college]. (Mario, Puerto Rican male1): We don’t use words that are in the dictionary? We make up our own words. You get so used to talking like that you talk like that in class. You talk to your friends like that. You get used to talking like that in general. My mother knows that I talk like that ever since I was little. But if it is something like real professional like when I go to my job core meeting, I change my ghetto language to proper English. (Selena, Puerto Rican female) Mario and Selena are 10th grade students who are daily negotiating their futures while attending Denver High School. Like their peers, they candidly share who and what is influencing their understandings and decisions about going to college. In many ways they are making meaning of and negotiating the multiple dimensions of their identities and K-16 college going policies and practices in their multiple worlds of school, work, peers, extracurricular activities, and family (McDonough, 1997). For example, 23 of the 25 youth in the study are involved in paid work or extracurricular activities and all of the youth participate in an ever increasingly complex testing culture. Yet, there is little data on how youth's perspectives and their negotiations of college-going processes in their multiple worlds effect how they identify and utilize institutional and interpersonal structures within K-16 college reform efforts. Many studies analyzing college-going processes have been limited to surveys, 1 All names used throughout the article are pseudonyms. 2 longitudinal questionnaires, or qualitative methods to research youth’s college aspirations and choice during their senior year only (McDonough, 1997; Horvat, 1996). They have been extremely helpful in understanding college choice and access to postsecondary institutions but they fail to specifically address how Black and Latino/a youth are making sense of and daily negotiating college-going processes as early as the 9th and 10th grade. Moroever, the exclusive reliance on outcomes has begun to yield to more recent research of quantitative and qualitative assessments to examine student’s processes in K-16 efforts (Nora, 2002). In order to better understand how ethnographic research can inform previous research on college preparation and current K-16 policies, structures, and practices, I examine the role of youth’s agency and their interpretations and negotiations of college-going processes in the 9th and 10th grade in this article. Important goals of this ethnographic study utilizing feminist theoretical lenses are: 1) to draw attention to the interplay between the City University of New York’s (CUNY) state level college admissions policies and the daily lives of poor and working class, Black and Latino/a college-bound youth in and out of school contexts; 2) to illuminate how youth employ their agency in interpreting and negotiating college-going processes; and 3) to recommend more equitable K-16 policies, structures, and practices to facilitate youth’s access to CUNY senior and junior colleges. To support these goals, I conducted research with 25 poor and working class, Black and Latino/a youth negotiating CUNY admissions policies, the multidimensionality of their lives, and K-12 institutional and interpersonal structures within college-going processes during a two-year period.2 2 The research reported in this article was made possible by grants from The Small Research Grants Program of the Spencer Foundation and The National Academy of Education/Spencer Postdoctoral Fellowship. The data presented, the statements made, and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. 3 In the following sections, I first provide a brief overview of the conceptual framework of K-16 college preparation reform efforts in K-12 schools and after school programs. I then outline the changes in CUNY’s admission policies ball before discussing the context of the study and the methodological framework. This study’s findings suggest three encompassing themes of K-16 reform efforts that 10th grade poor and working class, Black and Latino/a urban youth negotiate. These include: 1) challenging negative perceptions and expectations of urban college bound youth, 2) “passing” academic coursework, and 3) connecting varied testing cultures. I define youth’s negotiations as the ways in which they utilize their agency to interpret, critique, utilize, and change institutional and interpersonal structures such as the peer structure in and out of school contexts. Thus, the study seeks to inform both those who shape youth policy and those who work directly with youth in urban areas such as researchers, policy makers and educators to improve youth’s educational experiences, promote high school graduation, and provide more equitable access to, retention within, and graduation from a range of postsecondary institutions. College Preparation and Youth’s Perspectives in School Reform Efforts Increasing demographic shifts and policy changes in college admissions and remediation, and a high-stakes testing culture have evoked debates at the national, state, and local levels over promoting access to postsecondary institutions. Many argue that these postsecondary policy changes will promote excellence for all youth. Yet, others contend that these policy changes perpetuate inequitable K-16 structures and limit access to four-year campuses and college degrees for poor and working class, Black and Latino/a youth from urban communities. This is especially important as students like Mario and Selena who represent these populations continue to be underrepresented at higher education institutions relative to their representation in the traditional college-age population (Gandara, 2002; Nettles, Perna, & Freeman, 1999). To create 4 more equitable structures for postsecondary access, schools have begun to reform their policies and practices, but they now must move towards understanding the multidimensionality of students’ identities and lives in multiple worlds. The analyses of youth’s negotiations of K-16 college reform efforts can inform and shape policies, practices, and structures to promote retention in high school and more equitable access to postsecondary institutions. Therefore, this review blends three lines of research on college preparation: 1) K-16 school-centered reform efforts, 2) college preparation programs, and 3) youth’s perspectives on school reform efforts. K-16 school-centered reforms focused on college preparation are few in number (Gandara, 2002; Jones, Yonezwa, Ballesteros, & Mehan, 2002; Knight, Bentley Ewald, Dixon, & Norton, 2002; McClafferty & McDonough, 2000). However, some of these reforms ask that schools and others within the broader culture make changes over what Oakes, Quartz, Lipton, and Ryan (1999) call technical, cultural, and political dimensions at play within schools. Changes to technical dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures such as those relating to organizational, pedagogical, and assessment strategies, teacher student relationships, and resource distribution are viewed as vital to the reform process. For example, curricular, pedagogical, and organizational strategies have been created to prepare students to increase scores on SAT, ACT, and Regents exams in order to meet more stringent college entrance requirements. Yet, analyses of equity-minded school reform efforts reveal the interconnectedness and disparities between cultural dimensions of the norms, beliefs, and values about poor and working class and or ethnic minority college-bound youth and the political dimensions of the distribution of resources operating within local school contexts and postsecondary institutions (Oakes, Roger, Lipton, & Morrell, 2002; Oakes, Quartz, Ryan & Lipton, 1999). These three dimensions, the technical, cultural, and political, are inextricably linked and must be viewed in 5 tandem to understand the complexity of K-16 reform efforts to assist those most drastically effected by changing college policies such as those in New York, California and Texas. Similarly, the literature on restructuring college preparation programs for urban students also highlights increased access to college when situated within technical, cultural, and political dimensions of reform efforts. Researchers of college preparation programs have also pointed out the necessity for the technical structures supporting a college-going culture, youth’s collegebound identities, financial assistance, peer/study groups, high quality teachers, and a curriculum and pedagogy that facilitates the acquisition of academic capital or rigorous academic training, and family involvement (Gandara, 2002; Jun & Tierney, 1999; Knight & Oesterreich, 2002; Tierney & Hagedorn, 2002). Additionally, understanding youth’s negotiations of test preparation and acquisition of academic problem solving skills are identified as imperative to widening access to and achievement for traditionally underrepresented youth within postsecondary institutions, including Black and Latino/a youth from under resourced urban communities (Hagedorn & Foley, 2002). However, any type of menu or “cookie cutter” approach to technical aspects of programs focused on college preparation is simply not enough (Jun & Tierney, 1999). This approach leaves unexamined the cultural dimensions, such as the enacted beliefs, norms, and student diversity operating within after school college preparation programs, and how they shape curriculum, pedagogy, educational resources, and organizational policies. For example, teaching strategies emphasizing students’ cultural backgrounds in college preparation programs are essential for achieving success (Gandara, 2002, Tierney, 1999). Additionally, reflective systematic evaluation of the technical, cultural, and political dimensions operating within college preparation programs can support the increased improvement of specific organizational policies, 6 structures, and practices by maximizing the program’s resources to successfully support urban youth’s college access (Gandara, 2002; Tierney, 2002). Unsurprisingly, the perspectives of youth in systemic school-wide reform efforts have been missing from much of the literature on school change. Corbett and Wilson (1995) suggest that the “under-representation of students’ voices in research and reform is more substantive and practical and has to do with a mostly unexamined, generalized ascription of subordinate status to the student role” (p. 6). Yet, recently, the importance of youth’s interpretations of schoolcentered reform efforts and those of youth-based organizations has become increasingly significant (Cook-Saither, 2002; Heath & McLaughlin, 1993; Wilson & Corbett; 2001). There is also a growing thread of K-16 college preparation research examining youth’s understandings of the intersections of state college admissions policies, the realities of their daily lives in multiple worlds and the influence of college-going processes (Jones & Yonezwa, in press; Knight & Oesterreich, 2002; Knight, Bentley Ewald, Dixon, & Norton, 2002). Youth are making meaning of and responding to changing college admissions policies and institutional and interpersonal structures of systemic school-wide college focused reforms. For example, the perspectives of student inquiry groups support previous college preparation research in understanding the role of teachers’ lowered expectations and the rigor needed for curricular and pedagogical practices for low-income and/or students of color in order to create more equitable school policies and practices in the midst of reform (Jones, Yonezwa, Ballesteros, & Mehan, 2002; Jones & Yonezwa, in press). These student inquiry groups provided a way for researchers and students in collaboration to critique and act upon the ways teachers’ constructions of students and their curricular and pedagogical practices hindered teacher-student learning relationships and more specifically students’ educational experiences. 7 CUNY Admissions Policies Policy formulation and implementation is situated within historical, economic, sociopolitical, and cultural forces (Marshall, 1997). Presently, the City University of New York (CUNY) enrolls 350, 000 students in the 17 undergraduate colleges, 11 senior colleges and 6 community colleges, throughout the five boroughs of New York. Historically, CUNY has held a distinctive role within the community of institutions with open admission policies since 1970 with its emphasis on access at the baccalaureate level as the nation’s largest municipal university system. This emphasis has provided opportunities for the poor, working class and ethnic minorities to access four-year colleges at a much higher rate than other state open admissions policies focusing on access to community college (Lavin &Weiniger, 1999a, 1999b). However, the CUNY Board of Trustees resolved in 1998, “that all remedial course instruction shall be phased-out” of the CUNY senior colleges. After the discontinuation of remediation, any student who had not passed all three Freshman Skills Tests in essay writing, reading comprehension, and mathematics, and had not met other admission criteria, including mandated SAT scores, would not be able to enroll or transfer into the CUNY senior colleges (Hershenson, 1998). These changes in the open admissions policy of CUNY primarily work against New Yorkers from working class, poor, and immigrant backgrounds (Lavin & Weiniger, 1999a, 1999b). Implementing these changes would “shift 30% of White [applicants] out of senior CUNY institutions and into community colleges, [and] more than half of Asians, Blacks, and Hispanics [applicants] will be diverted to the latter” (Lavin & Weiniger, 1999a, p. 4). The CUNY trustees have created two exemptions to the passing of the three achievement tests. First, students are exempt if they score 500 or more on each section of the Scholastic Aptitude Test. Second, students are also exempt if they score 75 or higher on the New York State 8 Regents examinations in English and math (Lave & Weininger, 1999b). Currently, students may begin taking the achievement tests as soon as they have been accepted to a senior college. They must pass the three tests before they can register. If they do not pass the three tests, they are automatically referred to one of the community colleges. The changes in achievement test requirements and remediation policies in CUNY’s admissions requirements highlight the importance of effectively identifying policies and practices preparing students for access to and entry into postsecondary education at the baccalaureate level. Study Context and Methodological Framework To better understand youth’s negotiations of college-going processes in and out of school contexts through 9th and 10th grade, two questions guide the study. First, who and what influences poor and working class, Black and Latino/a youth’s understandings of college-going processes? Second, how do poor and working class, Black and Latino/a youth negotiate these influences on their college-going processes? The research team conducted the ethnographic study from 2000-2002 at Denver High School, a comprehensive public high school engaged in college-focused reform efforts in New York City. To inform their college policies, structures, and practices around disparities in facilitating college access across two of the nine houses within Denver High School, administrators agreed to support the research and chose the two houses, B and J house, that would participate in the study. Denver High School has a population of 3500 students comprised of at least 70% African-American and Latino/a students from under resourced urban neighborhoods. Forty – three percent are males and 57 % are females. Over 80.5 % of the student population is eligible for free and reduced lunch. The primary study participants are 25 youth from the two houses that send the majority of students to CUNY. Thirteen of the youth are male and 12 are female. 9 Seventeen are Black, Ghanaian, and Jamaican and 8 are Puerto Rican and Dominican youth who were selected by a community nomination process in 9th grade (Ladson-Billings, 1994). The process involved asking 9th grade teachers, counselors, administrators, parents, students, and security guards in the school to create a list of up to ten college- bound students who they believe are involved in multiple worlds such as work or extracurricular activities after the first two months of school. The four-member research team, consisting of the professor and three graduate students, engaged in the following data collection procedures from 2000-2002. 9TH GRADE COHORT (2000-2001) 10TH GRADE COHORT (2001-2002) 27 youth interviews 32 interviews of 9th grade counselors/teachers 22 youth in 6 focus group interviews 27 youth observed in their classrooms 24 youth co-researcher interviews of family members. Weekly school-wide observations of college fairs, parent association meetings, student award ceremonies, the testing culture, and extracurricular activities, to better understand the broader school culture and college going processes. Collection of written documentation about the stated goals and objectives of schoolwide college focused reform processes. 25 youth interviews (2 students moved) 21 interviews of 10th grade counselors/teachers 21 youth in 5 focus group interviews 25 youth observed in their classrooms Scheduling youth co-researcher interviews with an older peer.* Weekly school-wide observations of college fairs, parent association meetings, student award ceremonies, the testing cultures, and extracurricular activities. Collection of written documentation about the stated goals and objectives of schoolwide college focused reform processes. Completion of 24 youth surveys * We will continue to collect data during the months of July-August. We conducted analyses as part of an on-going, simultaneous, and iterative process. Data analysis was initially coded for each participant and across data sources around emerging themes such as future aspirations, agency, youth’s relationships with teachers and peers, test preparation, 10 admission policies, and extracurricular activities as well as technical, cultural, and political structures. Negotiating college-bound identities, academic coursework, and testing cultures In creating a high school college-going culture across grades 9-12, research shows that students’ early preparation, awareness and exposure to college-related information requires institutional and interpersonal structures such as the support and assistance of dedicated leadership and personnel (McClafferty & McDonough, 2000). In creating a college going culture within a high school, the technical, political and cultural dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures are essential for youth to make well-informed decisions in preparing for and choosing a college/university, and particularly to enable them to successfully negotiate college-going processes during their 9th –10th grade years. Also, early awareness better equips youth to handle the rigors of college preparatory academic courses, college related information, including school and state policies on earning credits, requirements for college and university admissions, and the differences and expectations of tests such as the Regents, PSAT, and SAT. Denver administrators engaged in this research study with the condition that the research team share with them information about the policies, structures, and practices that facilitated and/or hindered the creation of a 9th –10th grade college-going culture. Institutional and Interpersonal Structures The research literature on restructuring college preparation practices calls attention to the importance of high quality teachers and curricula and pedagogical practices that facilitate the acquisition of rigorous academic training and preparation for college entry and related exams. Denver High School has several commendable technical dimensions of institutional structures in place to create a school-wide college-going culture. They include the presence of house counselors, two school-wide college counselors, the Morton Learning Center, testing coordinators, cross-age 11 extracurricular activities such as sports, clubs, and electives, and CUNY high school liaisons who present admissions requirements in English classes. The school also offers rigorous academic courses and tutoring for academic help and Regents and SAT test preparation. Interpersonal structures of college counseling and academic supportive relationships extends beyond the counseling staff to include other faculty, staff, and youth’s peers. Although a few youth mentioned having college related conversations with their English or Music teachers or attending the school-wide tutoring program, the majority of college related conversations and activities taking place at Denver high school for 9th and 10th graders is occurring with dedicated personnel and youth’s peers in cross-age activities, clubs, and sports. For example, youth reported going to college fairs with 11th and 12th graders from the track team, having access to tutoring sponsored by the baseball team and ROTC, and receiving information about financial aid and specific colleges from older high school team/club mates and alumni who came back to visit. Yet many youth who do not participate in these cross-aged structures do not have access to such benefits. In order to create and sustain a college going culture for all 9th and 10th graders, information sharing cannot be left to the chance of occasional personal relationships that are formed between people. More systemic policies have to be put in place for cross-age interactions focused on college going. However, as the research literature on college preparation demonstrates, understanding the technical dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures that youth negotiate in and out of school contexts is necessary but not enough to facilitate greater access to college. Through focus groups and individual interviews, participant observations, and written documentation, youth reveal the ways they interpret and negotiate cultural and political dimensions of negative perceptions of urban youth’s college-bound identities, the “passing” of academic coursework, and disconnected testing cultures influencing their college-going processes. 12 Negotiating Perceptions and Expectations of Urban Youth’s College-Bound Identities The study’s findings draw attention to the intersections of urban youth’s identities, and their agency in shaping their interpretations and the impact of their class participation within cultural and political dimensions of interpersonal and institutional structures within their high school. For example, McClafferty and McDonough (2000) argue that the expectations that teachers, parents and other adults have of youth as college-bound’ or non-college bound “have a profound impact on the choices that students make, the options they see for themselves and what is realistic” (p. 1). More specifically, youth in this study discussed their classed-raced-gendered negotiations of negative perceptions and expectations of them as not “college-bound.” These perceptions and expectations were based on negative stereotypic images of poor and working class, Black and Latino/a male and female youth’s self-representations of their college going identities through dress, hairstyles, and language. Youth responded by employing varied negotiation strategies in school and work contexts to affirm their college-bound identities and to facilitate or contest teacher’s expectations of which youth are perceived to be “college bound” within K-12 policies, structures, and practices (Fordham, 1996; Valenzuela, 1999). During the following focus group conversation consisting of two Black males and one Latina female, Amy, one of the university researchers, posed the following two questions: What makes people see you as or think of you as college-bound and how do you negotiate the way people perceive you? Amy went on to note that it could be related to an activity, like a sport a student is involved in. Youth revealed the ways that they interpret, critique, and act to sustain their college-bound identities in the following excerpts. Dennis (Black male, football player): Just by walking through the door, when they first look at me all my teachers think that I am going to cause trouble, the way that I dress, I talk. 13 Amy (university researcher): … Why do you think they look at you and think you are going to cause trouble. What is it about your appearance and the way you talk? Dennis: Baggy jeans, long white t-shirts, the way I talk. Amy: How you talk? Selena: (Latina female, Job Core): Ghetto talk. I have that same problem. The teacher said you’re a white girl with a spic last name, cause I am half Italian on my father’s side. When I first came in a big t-shirt, sweat pants, she looked at me and told me to sit in the back like a kindergartener when they do something wrong and you tell them to sit in the back. Amy: This is just from walking through the door. Selena: Yeah. Amy: What do you guys do with that—how you are being perceived? Just by walking through the door and what you have on? How do you negotiate that? Selena: Me personally, I don’t care how they look at me. I don’t care. You’re not going to pay my bills. You’re not going to pay my rent. I don’t just worry about what you have to say. I just prove them wrong. That’s just me personally. Amy: Are you experiencing any of that Abraham? Abraham: (Black male, highly motivated, basketball player): Sometimes, when I have braids. When I just started passing the tests, when I do my class work, homework—that is when they started to pay attention to me. Selena: I know they look at him and think he is a thug. I know. I have seen it. Youth respond to self and teacher expectations of their college-bound identities in a variety of ways. They are individually analyzing, critiquing, and mediating cultural perceptions of themselves as college bound. Some of the Black male youth like Dennis and Abraham who 14 maintain B averages and believe that they are academically competent negotiate negative perceptions and expectations of their self representations as being college-bound by doing well on academic tasks such as class work and tests, thereby gaining teachers’ approval as they prove that they are college-bound. On the other hand, U.S. born Puerto Rican females like Selena did not individually seek the approval of teachers to prove they are college-bound in academic contexts. They affirm and support their educational aspirations outside of school contexts (Quiroz, 2001). Selena strategically negotiates the use of ghetto language and proper English in her work world to challenge negative Latina stereotypes of her college bound identities. Although Selena does know the difference between varied forms of speech, ghetto talk and proper English, she does not seek teachers’ approval by using proper English. Rather, she asserts her college bound identities in the work place. She proves her teachers wrong by using proper English on her job as seen in the following excerpt. Amy: And you guys said also about the way you talk? What is it about the way you talk? Selena: We don’t use words that are in the dictionary. We make up our own words. You get so used to talking like that you talk like that in class. You talk to your friends like that. You get used to talking like that in general. My mother knows that I talk like that ever since I was little. But if it is something like real professional like when I go to my job core meeting. I change my ghetto language to proper English. Amy: Does this happen at school too? Selena: They [teachers] try to correct you. When you say a certain word they like to correct you. They say it’s not proper English. 15 The above focus group conversations provides insights into the ways high school students who see themselves as college-bound interpret and negotiate cultural perceptions of their college-going identities and their schooling-career connections (Quiroz, 2001). For example, Selena maintains a positive understanding of her bicultural identity while negotiating negative stereotypes that she is uninterested in education and not going on to college because of dress and language styles. For U.S. born Latina students like Selena, her negotiations of language use in school and work contexts raise important questions: What are the cultural dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures in place at school and work which affirm her college bound identities in such a way that she decides to use ghetto talk and proper English in the workplace and not in school? Will her work or career identity as mediated through language continue to sustain her college bound identities and prove her teachers wrong? It is imperative that educators begin to understand and link the ways youth negotiate the cultural perceptions and expectations of themselves as college-bound in their school and work worlds and how these cultural perceptions and expectations impact their high school, college bound, and career identities. Valenzuela’s (1999) findings resonate with this study as she notes the various ways that U.S. Mexican youth must also negotiate teachers’ “displeasure with [their] selfrepresentations…the way, youth dress, talk, and generally deport themselves ‘proves’ that they do not care about school” (p. 61). She argues that teacher’s of U.S. Mexican youth tend to overinterpret urban youth’s attire and off-putting behavior as evidence of a rebelliousness that signifies that these student’s ‘don’t care’ about school. Having drawn that conclusion, teachers then often make no further effort to forge effective reciprocal relationships with this group. Immigrant students, on the other 16 hand, are more likely to evoke teacher’s approval. They dress more conservatively than their peers and their deference and pro-school ethos about school are taken as sure signs that they, unlike the ‘others’ do ‘care about school’. (p. 22) Rather than subtracting U.S. Mexican youth’s cultural identities, Valenzuela (2000) asks educators to consider the interpersonal structures that can affirm students’ cultural identities within schools. Dennis, Selena, and Abraham are informing policy makers, educators, and researchers in the ways in which the cultural dimensions of the interpersonal structures between teachers and students affirm their college bound cultural identities, their self-expressions of dress, talk and behavior in which they can clearly negotiate and shift between and among academic and work contexts. Negotiating Academic Coursework Research demonstrates that early awareness better equips students to handle college related information including state and school policies on earning credits, requirements for college and university admissions, including the role of academic coursework, extracurricular activities, and the differences and expectations of tests such as the Regents and SAT. Many of the youth enacted their interpretations and negotiations of these policies by employing the concept of “passing” as they make meaning of technical, cultural, and political dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures. One of the Latino males and 3 of the Black female students in the study are well aware that their counselors come find them to encourage them “to get your grades up in a certain subject” and “if the counselors think that you are going on to college, they give you certain classes.” Yet, very few of the 25 youth are aware that their counselors are engaging in these specific activities with a small group of their peers. Many of the youth seem to be negotiating 17 from a vague general idea of having the right courses. They talk about friends who have “all those credits but didn’t take the right courses.” In some cases, youth desirous of a future career in medicine, who are unaware that they are in a 3-term science sequence that takes up to 1½ years to complete, do not realize that they will be ineligible for pre-med programs in many of the private universities which require 4-years of high school science. When asked what they think are the requirements for going on to college, the youth reveal the negotiating strategy of “passing.” Abigail: That’s all they tell us [teachers, friends, peers, seniors]. Have money to be there. You have to pay. Left and Right. Left and Right. Jackie: To get an application you have to pay for it. Abigail: Whether you go to the school or not. Jackie: That is the thing that hurts. Abigail: You have to pay just to apply. They say, make sure that you pass your classes. They say, go to your classes. Michelle: Do they specifically say what classes you need to pass? Abigail: Everything. Everything and anything that you can get. You need to pass everything. They say that’s what colleges look at –to see if you are active or not. They look at freshman year too. A lot of people don’t know that. A lot of people mess up freshman year. Jackie: Oh freshman year isn’t nothing. You can make it up. But freshman year they look to see how you started off and then 11th grade. Maria: Oh yeah, in their freshman year they get a 65 and now they get a 95 or 94, but the 65 pulls them back. I saw this girl. She said don’t fool around. I have to go to summer school. I still have to make up credits. Abigail: I am going to pass everything. 18 In several of the focus groups, understandings of the necessary college admissions requirements in 10th grade versus 9th grade is situated with concepts of “passing all your classes,” and “maintaining an 85 average.” However, across the 25 youth and teachers, counselors and administrators interviewed over the two years, all overwhelmingly agree that math is a subject where youth are experiencing increased difficulty. Both teachers and counselors expressed uncertainty with changing math curricula and the content and expectations for Regents exams. Yet, according to recent news reports, low student performance in math is not unique to Denver High School, but is a city-wide issue (New York Times, 2002). Youth in the study illuminated difficulties arising in class when teachers use pedagogical practices that provide Regents-like examples and answers rather than providing full explanations and allowing them to grapple with concepts (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2000; Wilson & Corbett, 2001). Youth who felt more successful in math had teachers who allowed them to work in groups with others, provided more time for questions, and broke concepts up into smaller conceptual groupings. Youth who felt least successful in math identified teachers using only a lecture style, individual work sheets, and pedagogical practices that kept math separate from their multiple worlds of work, family, and peer interactions. Denver High School has generated several institutional structures including double periods of math and tutoring that can attend to some of the math learning needs of college-bound youth. Youth, however, noted that it is not beneficial to repeat double periods of math with a teacher whose class they previously failed or with a teacher who tutors using similar pedagogical strategies that have made course content inaccessible. Many of the 10th graders were made increasingly aware of tutoring by peers, counselors, and family members. Some who were unable to attend Denver’s math tutoring structures due to conflicts in schedules such as work, other academic priorities, extra curricular activities, or family obligations, turned to other resources. For instance, two youth took tutoring at 19 one of the senior CUNY colleges. Attending to a variety of time schedules for tutoring and the strategies used in tutoring and math classes would improve youth’s’ success in math. Increasingly, passing all their classes seems to be the negotiating strategy that many of the youth are employing. This negotiating strategy will ensure that many of the youth graduate from high school. However, embedded within this negotiating strategy may be the very mechanisms that limit student’s access to a range of postsecondary institutions as it remains at a surface level understanding of specific academic course requirements needed for enrollment into a range of postsecondary CUNY institutions. Negotiating Disconnected Testing Cultures Due to the multiple testing cultures at Denver High School and the presence of other technical, cultural and political dimensions of institutional and cross-aged interpersonal structures of care, 10th grade youth are increasingly aware of Regents exams and their importance for high school graduation but not CUNY college admissions requirements. By the end of 9th grade and the first semester of 10th grade, youth expressed confusion about how to prepare for these exams, the meaning that they hold for their high school, and the score expectations on their colleges of choice even though 9 of the 25 youth participants took Regents examinations as freshmen and each was scheduled to take at least one by the end of their sophomore year. Near the end of the 10th grade year, youth listed various ways that they are preparing for the exams, although some of the youth still had no idea which Regents Exams they would be taking two weeks before the three hour exams are to be given. Their negotiations of Regents preparation now includes creating their own peer study groups, attending tutoring sessions, buying the Regents Exam books, and taking practice exams on the Internet. However, there continues to be uncertainty among youth, teachers, and counselors about the significance of the connection between academic courses, Regents, and college admissions 20 requirements as well as the coordination of technical, cultural and political dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures such as the CUNY high school liaisons to more systematically address this connection. Some youth receiving resource room services are receiving mixed messages about the requirements they must meet for Regents exams. They believe that they do not have to pass Regents in order to graduate. Furthermore, youth continue to show only a vague understanding of the PSAT and SAT exams and their importance to college going at the beginning of 10th grade. Only two 10th graders mentioned being informed about the PSAT. In fact, the only 10th grade youth in the study who took the PSAT exam was signed up and encouraged by her mother. The other youth declined the chance to take the exam because it was held on Saturday which is her religious Sabbath. Her decision to not take this exam highlights the types of decisions that youth make while negotiating their multiple worlds and college-going processes. While some youth focus on the lack of preparation by institutional and interpersonal structures at the school for Regents and SAT Exams, other youth like Tammy, Mario and Patrick discuss their nervousness, fears, headaches and decisions that they need make now that they are 10th graders and “college is closer.” Amy: (1st Interviewer, Black female): How do you think your thinking about college has changed since last year [as 9th graders]? Mario (Latino male): It brings more headaches. (much laughter) Yeah. Right. Lynn: (2nd Interviewer, Black female): Like what? Keep going Mario? Mario: Like I am almost graduating, the more I think about it. Headaches. Amy: What kinds of things are you having to think about differently? Mario: Like which one to choose. There’s a lot. Like I am trying to get a good score on the SAT. That is giving me a headache. And then, the Regents aren’t helping either. And then that’s it …and what they expect you to have to go [to college]. 21 Amy: How do you find out more about what they are expecting? Tammy (Black female): As far as college goes, I am scared. We have two years left. This year is almost over. Regents are coming up. We have SAT’s coming up? All this other stuff --not to mention extracurricular. Lynn: What are you worried about specifically? Can you name one of two things that have you worried? Tammy: Everything. Just Everything. I do well on tests but I am just nervous. I have a bunch of Regents. College is getting closer. Lynn: What Regents are you taking? Two Math Regents, Spanish Regents , History Regents, and AP English. Although some of the students like Tammy and Mario know which Regents they are taking, many of the students want to know which tests that they will be taking and are asking for more time to prepare for them. However, organizational policies within the school prevent many of the students from learning which tests they need to take and when they will be held. Youth like Jackie who passed one of the Regents Exam in 9th grade with a score above a 75 do not have any understanding that this score would exempt them from one of the CUNY achievement tests. This exemption would bring them closer to eligibility to attend a senior CUNY and perhaps alleviate some of their fears about future exams that they will have to take. Additionally, as 10th graders, youth like Tammy are sharing their fears and nervousness around taking all of these exams yet do not express how they will negotiate their fears and headaches with college getting closer. Cultural and political dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures such as the college fair held at Denver high school with representative from CUNY also appeared to be a 22 place of “policy slippage” (Marshall, 1997). Resources, although provided, are unequally distributed and do not specifically address testing admissions score requirements or exemptions needed for senior CUNY colleges. For example, Denver High School supports two college fairs throughout the year. This year the college fairs were opened up to 10th graders as well as to 11th graders. During the college fair held in the spring 6 senior universities of the 10 universities within the CUNY system were in attendance. Students received a handout of questions from one of the school-wide college counselors to ask college representatives. None of the 36 questions focused on the required tests or the scores needed for eligibility to a senior CUNY college. Moreover, the available Freshman Admissions Guide to the CUNY (2002) states that baccalaureate applicants must demonstrate readiness for college-level work in English and mathematics. They may demonstrate this by attaining a certain level of achievement on the SAT, ACT, or New York State Regents examinations, by passing the CUNY Skills Assessment Test or by other criteria determined by the CUNY Board of Trustees. (p. 5) Thus, although some of the students from the study attended the Spring College fair, there is no place within the Denver High School Questionnaire to prompt youth to ask questions about testing requirement nor does the Freshman Admissions Guide to CUNY specifically state the score needed on Regents exams to be exempted from the CUNY Skills Assessment exams. Creating a college-going culture for all youth that is responsive to their multiple worlds means helping youth understand the significance of such CUNY achievement tests early on and increasing their awareness of alternative testing options that accommodate for diverse religious beliefs. Moreover, working with youth, families, teachers, peers, and counselors at large means clearly understanding and sharing information about requirements and exemptions of CUNY achievement tests in order to be eligible for baccalaureate programs in senior CUNY colleges. 23 As 10th graders reflected on 9th grade and their futures as college-bound youth, they discussed the need to have teachers who evenly spread out review and Regents connections throughout each semester of the year, rather than reserving it for that time immediately prior to testing. They prefer this type of preparation rather than pedagogical practices which create and sustain anxiety for youth by last-minute cramming or the decision to focus only on very technical aspects of a subject which neglect to deepen youth’s' understanding of concepts and impact their success on tests for increased eligibility to senior CUNY colleges. Both youth in the study and those observed in House offices have desired and utilized schedules given out for Regents exams, so they can plan programs of study earlier and more effectively around their busy schedules which may include babysitting, volunteering, attending religious services, playing volleyball, or participating in the band. The only schedule posted for June Regents Examinations is found on the school website. Moreover, in determining the allocation of resources and funding, 10th grade youth participants told us that varied tutoring structures for academic and testing preparation need to be offered at different times with a variety of people, including peer tutoring, tutoring by college youth, and/or Denver faculty and staff. Incorporating this feedback system from youth would help to coordinate existing, and establish new institutional and interpersonal structures that draw from youth’s agency, knowledge, and negotiations to assist in the implementation of a more supportive testing culture. This culture would link student’s interpretations and negotiations of academic coursework, standardized tests for high school graduation, and college admissions achievement tests. Implications for policies, practices and future research of K-16 reform efforts Recent changes in college admissions and remediation policies mandating more stringent entrance requirements to four year colleges necessitates increased attention to them and stronger 24 alignment between these higher education policies and K-12 systemic college focused school reform efforts. Ethnographic inquiry facilitated the focus on three interconnected areas of alignment among K-16 policies, structures, and practices to create a 9th and 10th grade college – going culture to support poor and working class Black and Latino/a youth’s negotiations of their futures and eligibility to a range of CUNY colleges. These interconnected areas comprise challenges to: 1) negative perceptions and expectations of urban youth as college-bound, 2) the “passing” of academic coursework, and 3) disconnected testing cultures. More specifically at the level of policy formulation and implementation, youth’s interpretations and negotiations of college-going processes in the 9th and 10th grade reveal the ways in which universities concerned with recruiting a diverse college-bound student populations will need to communicate the new standards and expectations of college admissions policies to high school personnel and youth (Gandara, 2002, McClafferty & McDonough, 2000; Nora, 2002). Access to CUNY senior colleges necessitates a focus on the technical, cultural and political dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures such as the CUNY high school liaison and the guide to CUNY admissions. Within these structures, CUNY outreach personnel can communicate the ways the academic curriculum, the extracurricular curriculum and the testing cultures of the high school shapes students’ access to a range of postsecondary CUNY institutions as early as 9th grade. In K-16 school-university partnerships, the emphasis on which youth have access to rigorous academic college preparatory curriculum is linked to perceptions and expectations of who is considered to be college-bound. This link is demonstrated by the decisions made of which classes the CUNY outreach personnel will serve in the high school. Wider access to all youth within the high school and the resources of CUNY personnel needs further facilitation within school-centered reforms. 25 Youth also reveal the necessity for teacher professional development learning opportunities to impact mathematics’ curricular and pedagogical practices to increase opportunities for eligibility to senior CUNY colleges (Gandara, 2002; National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2000; Jones & Yonezwa, in press). Although the majority of the teachers at Denver High School have master’s degrees and have been there longer than 5 years, the quality of instruction in mathematics does not lead to youth’s advanced understandings of mathematical concepts and preparation for college, but rather to the exact opposite as many of the youth languish in trying to “pass” their double math periods. In order to encourage all youth to pursue a range of postsecondary options, educators must be willing to provide multiple approaches to teaching and learning youth in subject area content. Teachers could benefit from pedagogical discussions with each other during professional development days that attend to multiple pedagogical practices for teaching mathematics, offer support in the reflection on teaching styles, and encourage one another to try out new pedagogical practices to facilitate youth’s movement through a math sequence that will prepare them for college. Creating a supportive testing culture that connects academic course work, and Regents, SAT exams and extra curricular activities or work responsibilities requires the coordination of several institutional and interpersonal structures to respond to youth’s multiple worlds in order for them to attend a range of postsecondary institutions. The coordination of structures includes attending to organizational timing policies, study skills, the balance between review and new learning, alignment of scores between Regents, SAT’s and CUNY Achievement tests as well as the allocation of resources and funding for varied learning tutoring opportunities. In creating a 9th and 10th grade college-going culture high schools also need to specifically examine school policies and practices to understand the impact of technical, cultural, 26 and political dimensions of institutional and interpersonal structures for increased access to college. In so doing, they can address the ways in which college-focused resources are being created and distributed among the entire school population. Attending to some of the following questions facilitates the creation and redistribution of resources and opportunities in K-16 school-centered reform efforts. For example, how do high school personnel determine who is college bound? Which youth are not participating in college-focused school reform efforts? Which youth have access to what resources within the college-focused reform efforts? In what ways are youth interpreting, utilizing and creating institutional and interpersonal structures to negotiate their identities and college-going processes? As Nora (2002) cogently articulates, while many researchers may believe that there has been a “saturation of interventions and initiatives” to address access to college, he argues that in the face of the persistent drop-out rates, especially between 9th and 10th grade, further research is needed to examine “why students forego their educational hopes and dreams” (p. 74). Thus, documenting and analyzing 9th and 10th grade youth’s interpretations and negotiations of college-going-processes for their futures highlights possibilities for research to impact the creation of more college-focused equitable structures that links student’s negotiations of K-16 policies and practices and eventual access to, retention within and graduation from a range of CUNY colleges. 27 References Cook-Saither, A. (2002). Authorizing Students’ Perspectives: Toward Trust, Dialogue, and Change in Education. Educational Researcher. 32(4), 3-14. Fordham, S. (1996). Blacked out: Dilemmas of race, identity, and success at Capitol High. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Gandara, P. (2002). Linking K-12 and college interventions. In W.G. Tierney & L.S. Hagedorn (Eds.), Increasing access to college (pp. 81-105). New York: SUNY Press. Heath, S. B. & McLaughlin, M. (1993). Identity and Inner-city youth: Beyond ethnicity and gender. New York: Teachers College Press. Hershenson, J. (1998). City University of New York trustees approve resolution to end remediation in senior colleges (pp. 103). New York: CUNY Office of University Relations. Horvat, E.M. (1996). Structure, standpoint and practices: The construction and meaning of the boundaries of Blackness for African-American female high school seniors in the college choice process. Paper presented at the annual conference of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago. Jones, M., & Yonezwa, S. (in press). Student voice, cultural change: Using inquiry in school reform. Journal for Equity & Excellence in Education. Jones, M.,Yonezwa, S., Ballesteros, E., & Mehan, H. (2002). Shaping pathways to higher education. Educational Researcher 31(2), 3-11. Jun, A. & Tierney, W. (1999). At-risk students and college success. A framework for effective preparation. Metropolitan Universities. 9(4), 49-60. 28 Knight, M., & Oesterreich, H. (2002). (In)(Di)Visible youth identities: Insight from a feminist intersectional framework. In William G. Tierney & Linda Serra Hagedorn (Eds.), Increasing access to college (pp. 123-144). NY: SUNY Press. Knight, M., Bentley Ewald, C., Dixon, I., & Norton, N. (2002). It’s (not) too early!: Linking postsecondary policies and outreach practices to high school reform. Paper presented at the annual American Educational Research Association, New Orleans. Lavin, D.E. & Weininger, E. (1999a). The 1999 trustee resolution on access to the City University of New York: Its impact on enrollment in senior colleges. New York: Ph.D Program in Sociology, Graduate School and University Center, City University of New York. Lavin, D.E. & Weininger, E. (1999b). New admissions policy and changing access to City University of New York’s senior and community colleges: What are the stakes? New York: Ph.D. Program in Sociology, Graduate School and University Center, City University of New York. Marshall, C. (Ed.). (1997). Feminist critical policy analysis: A perspective from postsecondary education Vol 2. Washington DC: Falmer Press McClafferty, K. & McDonough. P. (2000). Creating a K-16 environment: Reflections on the process of establishing a college culture in secondary schools. Paper presented at the 2000 Association for the Study of Higher Education, Sacramento, CA. McDonough, P. (1997). Choosing colleges. Albany: State University of New York Press. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: NCTM 29 Nora, A. (2002). A theoretical and practical view of student adjustment and academic achievement. In W.G. Tierney & L.S. Hagedorn (Eds.), Increasing access to college (pp 65-80). New York: SUNY Press. Oakes, J., Quartz, K., Lipton, M. & Ryan, S (1999). Becoming good American schools. The struggle for civic virtue in education reform. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Oakes, J., Rogers, J., Lipton, M. & Morrell, E. (2002). Outreach strategies and the social construction of college readiness. In W.G. Tierney & L.S. Hagedorn (Eds.), Increasing access to college (pp. 105-122). New York: SUNY Press. Quiroz, P. (2001). The silencing of Latino student “Voice”: Puerto Rican and Mexican narratives in eight grade and high school. Anthropology & Educational Quarterly. 92(3) 326349. Tierney, W. (2002). Reflective evaluation: Improving Practice in college preparation programs. In W.G. Tierney & L.S. Hagedorn (Eds.), Increasing access to college (pp. 217-230). New York: SUNY Press. Tierney, W. & Hagedorn, L. (2002). Increasing access to college. NY: SUNY Press Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling; U.S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. New York: SUNY Press. Wilson, B. & Corbett, H. (2001). Listening to urban kids: School reform and the teachers they want. New York: SUNY Press. 30