Assessing Reading Skills

advertisement

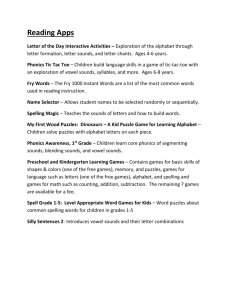

Assessing Reading Skills The process of reading consists of several skills which come together for a fluent reader. The skills are phonetic analysis, sight word reading, structural analysis, oral reading, and comprehension. The following reading skills typically are assessed with students who are struggling with reading: Phonetic Analysis Phonetic analysis is the process of decoding a new word by using the rules of phonics (the sounds of letters and letter combinations). Most children who are low in reading are poor phonetic decoders. In the early 1990's, when most schools went to a whole language reading approach and left phonics behind, many school systems (Texas & California were the first) experienced large dips in the reading achievement of their students. Now, the National Institutes of Health, having completed a 10-year longitudinal study of the acquisition of reading skills, recommends a return to teaching phonics. Special education never left phonics instruction and you will find that most remedial reading programs are phonics based. A child must be able to sound out a word without pictures or context present to become a fluent reader. However, you will find that many children who are struggling with reading you are unsure of even short vowel sounds. Are you sure what the "short" sound of each vowel is? A as in cat, E as in egg, I as in it, O as in office, and U and in umbrella? In the south we tend to pronounce our short e's and i's as if they were the same letter. For instance - listen to yourself say these two words: pen and pin. Do both words come out sounding the same? You must be sure that you train yourself to pronounce words correctly so that you do not confuse your students when you are teaching phonics! There are a several basic phonics patterns which are "regular"; that is, they can be applied in almost all cases and are frequently found in the English language. There are several phonics patterns which are "irregular"; in other words, they do not meet the rule of the regular pattern but are found in the English language frequently enough to be their own rule. For example “ar" is its own pattern, such as the “ar" as in “far.". It doesn't meet the cvc rule for short vowel sounds but it does occur often enough in the English language to be a rule in and of itself. Other examples include car, barn, start. The regular phonics patterns which typically are assessed include: Short vowel sounds with these patterns: cvc - e.g., can, set, big, pop, rub ccvc – e.g., flat, shed, trim, plod, club cvcc – e.g., mast, weld, dish, moth, such ccvcc – e.g., scalp, fresh, glint, block, trust Long vowel sounds with these patterns: cvce – e.g., bake, kite, pole cvvc - e.g., meet, meat Long vowel patterns within consonant blends: ccvce – e.g., choke ccvvc – e.g., bleak cvvcc – e.g., beach That is it for regular vowel patterns. When we assess the vowel patterns we have to be sure to include a lot of different consonants and consonant blends around the vowels so we get a good idea of the child's ability to decode consonants and consonant blends. When we assess a young student, we want to include many words from the patterns mentioned above because young children will not be very far along in phonics instruction. When we test older children, we frequently do not have to assess many words related to these simplistic patterns. Older children will need to be assessed on more examples of the irregular rules of phonics, unless the child is way behind in reading. Some irregular phonics rules: The sounds “ight, aught, ought, " as in tight, taught, bought. The sound “ay" as in stay. The sounds of irregular/silent consonants “gn, wr, kn" as in gnat, wrap, know. The sounds “oi, oy, ow, oo" as in boil, toy, cow, and tool. The sounds of “r controlled" vowels as in bar, her, bird, porch, blur. Sight Words There are some words in the English language which, for the most part, cannot be “sounded out" according to phonetic rules. These words occur so frequently in reading text that a person must be able to read the word automatically upon seeing it – hence the term “sight word.” There are many lists of sight words. The most famous is the “Dolch" list. Many criterion-referenced assessment devices, such as the Brigance, contain sight word lists. The Brigance word lists goes into higher grades than the Dolch list does. Be careful, however, about basal readers that give sight word lists. These lists come from the basal reader and may not include some important words. Any Ssight words a child consistently misses during an assessment should become part of their IEP objectives in reading. Many children, to hide their embarrassment, will read sight words very quickly, hoping that you will think they missed a word because they were going so fast you couldn't understand what they said. In order to keep children from reading too fast, there are several things you can do: 1. put the words on cards and show them one at a time 2. use a piece of paper to cover all the unread words and move it down the page one word at a time. Structural Analysis Structural analysis relates to morphemes. Phonemes are single sounds, such as the “k" in cat, and morphemes are the smallest meaningful unit of language. “Cat" is one morpheme, but adding “s" to cat, making it cats, changes the meaning. Therefore, the plural forms “s" and “es" are one morpheme each because they have meaning, as in boys, and beaches. All suffixes and prefixes are morphemes because they change the meaning of the words they are attached to. For example, done becomes undone when the morpheme (prefix) “un" is added. When we assess morphemes, including prefixes, suffixes, contractions, and compound words, we are analyzing whether or not the child can read the different structures of language, thus, structural analysis. Children in lower grades will not have been exposed to many of these structures, but new reading structures may occur all the way through the sixth grade. Oral Reading It is important to listen to a child read orally when assessing reading skills. By listening to children read, you can note whether they use context as a strategy or whether they rely upon phonics, or even whether they just guess. You can spot consistent mistakes. You can notice how they apply correction strategies or if they self-correct at all. You can listen to whether they stop at periods, use intonation, and pause at commas. Most importantly, you can ascertain whether their reading is fluent enough for them to actually understand the content of what they have read (comprehension.) One way to ascertain whether a child has enough reading ability to read from a content area text (e.g., social studies, science) is to perform an Informal Reading Inventory, or IRI. Here is how you design and administer an IRI: 1. Choose a subject area textbook (geography, social studies, health, etc.) 2. Find a chapter in the text that is just ahead of the chapter the class is completing. 3. Select a paragraph from that chapter. 4. Pick every 4th, 7th, or 10th word from the paragraph (depending on how long the paragraph is) and make a list of those words. Omit easy sight words like “the." 5. Your list should be between fifteen and twenty words long. 6. Have the student read the list. Do not correct the student's mistakes. (In fact, throughout all assessments you should not give students any feedback relative to their performance on the assessments. If a student insists on knowing how he/she is doing, give them a noncommittal response such as “you’re doing fine"). The IRI will tell you if the student is capable of reading the textbook in his/her class. If the student earns a score of 95% or higher on the IRI, she should be able to read the text with no help. If the result of the IRI is around 80 - 95% correct, then she can use the textbook with some help. But if the student falls much below 80% correct, she will be gaining very little meaning from that text. The teacher should make adaptations to the content so that the student does not have to rely on the text. Reading Comprehension The reason for reading is "comprehension." Comprehension relates to how much children remember and understand about what they have read. Many teachers fail to appreciate the full scope of comprehension. If you remember "Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives" you will remember that there are many levels of knowledge (and thus assessment of knowledge). The earliest form of knowledge is memory and word recall. More sophisticated forms of knowledge involve application, evaluation, and synthesis. Comprehension is the same way. It's one thing to recall names of major characters in a story, but quite another thing to suggest an alternative title for the story or to evaluate what might occur in the future of this story. There are three basic types of comprehension: literal, interpretive, and critical. Literal - understanding the sequence and facts that are explicitly stated; answering factual questions Interpretive - comprehending the information implied in the text; finding main ideas and cause and effect relationships; drawing conclusions; summarizing. Critical - involves the evaluation of the text; differentiating between fact and opinion; identifying the author's purpose and bias; recognizing propaganda techniques. If a child cannot read at all, or is a very poor reader, you may want to read the passages to him when assessing comprehension, and then ask him the questions. If you do this, be sure to note that you read the passages to him.