schooling behavioral

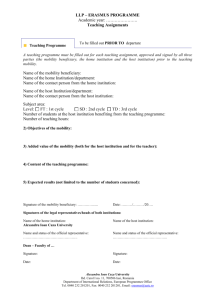

advertisement