Chapter Outline - Cengage Learning

advertisement

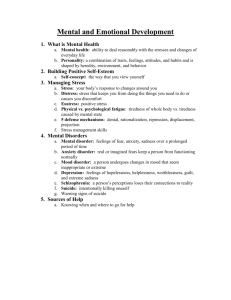

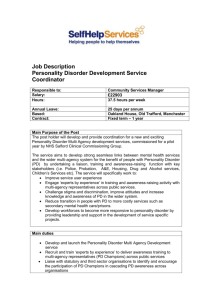

CHAPTER 8 CHAPTER OUTLINE I. Diagnosing personality disorders Personality disorders involve longstanding, inflexible, and maladaptive behavior patterns that produce personal and social difficulties, personal distress, or problems in functioning in society. They account for about 5 to 15 percent of admissions to hospitals and outpatient clinics; lifetime prevalence for all of them is 9 to 13 percent. Men are more likely than women to be diagnosed with some of the personality disorders, whereas women are more likely to be diagnosed with others. There are reasons to suggest that the gender distribution may be due to bias in diagnosing. Diagnosis is made on Axis II of the DSM, but diagnosis is difficult because symptoms represent extremes of normal personality traits, are rarely stable across situations, and may overlap with other disorders. Further, clinicians often render diagnoses inconsistent with DSM criteria. To be considered disorders personality patterns must cause significant impairment in functioning or subjective distress, a constellation of characteristics must be found, the personality pattern must characterize the person’s current and long-term functioning, and the pattern must not be limited to episodes of illness. Further, there may be questions about the universality of these disorders and the cultural validity of DSM-IV-TR personality disorders. II. Disorders characterized by odd or eccentric behaviors Paranoid personality disorder is characterized by suspiciousness, hypersensitivity, and reluctance to trust others. DSM-IV-TR estimates the prevalence of paranoid personality disorder as between 0.5 and 4.4 percent. Psychodynamic explanations emphasize the role of projection in the disorder, Schizoid personality disorder is marked by aloofness and voluntary social isolation. To avoid conflicts and emotional involvements, these people withdraw from others or comply superficially with requests from others. The relationship between this disorder and schizophrenia is not clear. Schizotypal personality disorder involves odd thoughts and actions, such as speech oddities or beliefs in personal magical powers, and poor interpersonal relationships. It occurs in approximately 3 percent of the population. Odd though their behaviors are, individuals with this disorder are not as impaired as people with schizophrenia. III. Disorders characterized by dramatic, emotional, or erratic behaviors. Prevalence is about 1 percent. Antisocial personality disorder involves exploitation of others, irresponsibility, and guiltlessness, and is far more common in men than women. In the United States, the incidence of antisocial personality disorder is estimated to be about 2.0–3.6 percent overall; rates differ by gender with more men than women diagnosed with the disorder. Borderline personality disorder is characterized by extreme fluctuations in mood: friendly one day, hostile the next. People with this disorder also lack identity, feel lost and empty they engage in self-destructive behaviors. The core aspects seem to be difficulty in regulating emotions, and intense, unstable relationships. Females are three times more likely to receive the diagnosis than men. The disorder has been conceptualized from a psychodynamic perspective (object splitting—either people are completely good or completely bad), a social learning viewpoint (conflict between attachment to others and avoidance of such engagement), and a cognitive approach (distorted attributions and assumptions). Histrionic personality disorder is marked by self-dramatization, exaggerated emotional expression, and attention-seeking behaviors. It affects 1 to 3 percent of the population. Biological factors, such as autonomic or emotional excitability, and environmental factors, such as parental reinforcement of attention-seeking behaviors, may influence the development of histrionic personality disorder. Narcissistic personality disorder involves an exaggerated sense of self-importance, exploitative attitude, and lack of empathy. IV. Disorders characterized by anxious or fearful behaviors Individuals with avoidant personality disorder desire interpersonal contact but fear social rejection; they avoid situations that might lead to criticism. Their primary defense mechanism is fantasy, and their social skills are weak. Prevalence is about 1 percent of the population, with no gender differences and there seems to be disagreement about whether it is a separate diagnosis from social phobia or an extension of that disorder. People with dependent personality disorder are characterized by an extreme lack of self-confidence, reliance on others for decisions, and an ingrained assumption that they are inadequate and must be cared for by others. Prevalence of the disorder is about 2.5 percent. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is marked by excessive perfectionism, devotion to details, rigidity, and indecisiveness. Unlike obsessive-compulsive disorder, there are no recurrent unwanted thoughts or ritualistic actions. Prevalence is about 1 percent, but a recent study place it at 7.9 percent with twice as many males as females having the disorder. V. Multi-path analysis of one personality disorder: Antisocial personality disorder. There has been an extraordinary amount of research in the biological dimension devoted to trying to uncover the biological basis of APD. Indeed, early researchers concentrated primarily on using genetics, central nervous system abnormalities, and autonomic nervous system abnormalities to explain the disorder. Under genetic influences many people have speculated that some individuals are born to “raise hell.” It is not uncommon for casual observers to remark that antisocials, criminals, and sociopaths appear to have an inborn temperament toward aggressiveness, sensation seeking, impulsivity, and a disregard for others. Central nervous system abnormality suggest that adults with antisocial personalities tend to have abnormal brain wave activity similar to that of young children. Other interesting research points to the involvement of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in the prominent features of APD. Genetic predisposition to fearlessness or lack of anxiety also have been investigated. Psychological dimension explanations of personality disorders and specifically APD tend to fall into three camps: psychodynamic, cognitive, and social learnin g. According to psychodynamic approaches, the psychopath’s absence of guilt and frequent violation of moral and ethical standards are the result of faulty superego development. Cognitive explanations of APD stress the relationship of core beliefs that influence behavior. These core beliefs operate on a nonconscious level, occur automatically, and influence emotions and behaviors. Learning theories stress a number of different forces in explaining APD: (1) inherent neurobiological characteristics that delay or impede learning, (2) lack of positive roles models in developing prosocial behaviors, or (3) presence of poor role models. In all cases, whether we are speaking about classical conditioning, operant conditioning, or social modeling, it is proposed that biology or social/developmental factors combine in unique ways to influence the development of APD. In the social dimension many factors that have been implicated in the development of personality disorders, but relationships within the family—the primary agent of socialization—are paramount in the development of antisocial patterns. The study of culture and personality has always been of fascination to early anthropologists who believed that culture shapes its development or that it represents an expanded extension of personality. Impulse control disorders are unrelated to personality disorders and are included in this chapter for the sake of convenience. These disorders involve an inability to resist the temptation to perform some act, a feeling of tension before the act, and a sense of excitement, release, and sometimes guilt afterward. Intermittent explosive disorder is marked by brief episodes of losing control, leading to destruction of property or assaults on other people. Kleptomania involves stealing, even when the article is not needed. It appears to be more common in women than men. Pathological gambling involves an inability to resist impulses to gamble and afflicts 1 to 3 percent of American adults. Cognitive-behavioral approaches focus on the erroneous beliefs gamblers have about their ability to influence outcomes that are governed by chance. Pyromaniacs repeatedly and deliberately set fires without the motive of revenge. Children who are fire-setters are more often boys than girls and have problems with impulsivity and hostility. Trichotillomania is the inability to refrain from pulling out one’s hair. It is probably more common in women than men; about 1 percent of college students have a past or current history of the disorder. VI. Treatment of antisocial personality disorder Owing to their lack of anxiety, antisocial personalities are poorly motivated to change. Behavior modification and cognitive therapies have been somewhat helpful, but effective treatments for antisocial personality are rare. The focus might be placed on youths, who are more amenable to treatment. VII. Implications. Although personality disorders have generated rich clinical examples and speculation, not much empirical research has been conducted to provide definitive insights into the causes of the disorders. Many researchers use the five-factor model of personality, which describes personality patterns in terms of neuroticism (emotional adjustment and stability), extraversion (preference for interpersonal interactions, being fun-loving and active), openness to experience (curiosity, willingness to entertain new ideas and values, and emotional responsiveness), agreeableness (being good-natured, helpful, forgiving, and responsive), and conscientiousness (being organized, persistent, punctual, and self-directed).