Librarian cornered by images or How to index visual resources

advertisement

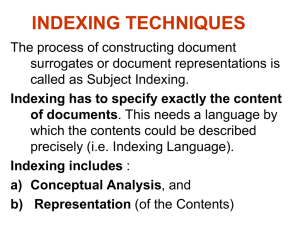

Librarian cornered by images or How to index visual resources Wanda Klenczon, Paweł Rygiel Wanda Klenczon, librarian at the National Library of Poland (1987- ), Head of Bibliographic Institute (2007- ), chair of Technical Committee Information and Documentation of Polish Standardization Committee. Responsible for the development of bibliographic standards used in the Polish National Bibliography, authority control and subject indexing (National Library of Poland Subject Headings, UDC). Paweł Rygiel, librarian at the National Library of Poland since 2008. Interested in image indexing and retrieval. Abstract Presenting museum, library and archive collections online has become a common practice in recent years. Among the data accessible via the Internet are visual resources such as paintings, drawings, engravings and photographs, which constitute a rich and vital source of information. Image indexing is an extremely difficult task. The crucial question is: how to transform the visual code of an image into written code. This paper presents standards of still images description, guidelines and indexation tools, advantages and disadvantages of their usage, their potential to provide authoritative and comprehensive access points to digitized resources and to support sophisticated search. In order to provide efficient access to the digitalized images presented at the National Digital Library Polona and to promote their re-use, we are looking for a model of images subject indexing. Introduction Digital technologies and the online presentation of digital images collections by libraries, museums and archives have enabled wide, absolutely democratic access to resources that 1 were previously available only for researchers. Among the data accessible via the Internet are visual resources such as paintings, drawings, engravings and photographs, which constitute a rich and vital source of information about art, but also about history of people and places, culture and tradition, social life, interests and customs… “While some image collections may be of interest only to researchers in a narrow field […], other image collections are being created that will be of interest to many, including the artist, the scientist, the educator, the historian, the journalist, the student, and the leisure seeker” (Jörgensen, 2003, p. 1). Availability of both digitalized images and their descriptions has placed them in a new context, while the ways of searching for information have also evolved (Jörgensen, 2003; Jansen, 2008). Moreover, descriptions have been subject to assessment and verification by users who access the freed resources. Collections and institutions may take advantage of this situation as it positively affects the quality of descriptions and helps complete the missing data (see Springer et al., 2008). Digitalization of images requires a lot of time, money and effort. An extremely difficult task that the cultural heritage institutions have to undertake is to assign high quality semantic metadata to the non-textual materials. Although the automatic recognition of images seems to be a very promising perspective, there are layers of meaning that can be indexed only by using human knowledge, experience and intuition. “Properties of an image such as shape, texture, and color contribute to our understanding of an image, but do not define it. Textbased search techniques remain the most efficient and accurate methods for image retrieval”. (Jörgensen 1999, 302; Neugebauer 2005). The National Library of Poland as the central library of the state and one of the most important cultural institutions in Poland is responsible for the preservation and promotion of the Polish cultural heritage. The National Digital Library Polona1 is the repository and the platform for enhancing access to the NL’s digital collections. The number of images (such as prints, drawings, photographs, postcards, posters, bookplates) among the digitized documents constantly increases. In order to provide efficient access to the digitalized images and to promote their re-use, a model of cataloguing and subject indexing should be 1 http://www.polona.pl 2 established. The main goal is to enhance access to both general and specific depicted objects, regardless of the knowledge level of users and their information competency. And last but not least, our intention is to achieve semantic interoperability between the various data and subject schemes used in the Polish libraries and museums communities. In this perspective a few questions should be answered: what vocabulary should be used? What description level would be useful? How could research results be maximized? Image indexing and retrieval – rules, tools and questions Subject indexing consists of the following sequence of steps: subject analysis, selection of information and its translation into the language of indexing i.e. transforming the message by changing its language without the loss of information, as far as possible (Chu & O’Brien, 1993; Lancaster, 1998). In the case of iconographic documents it also involves transforming visual code into written code, visual information into textual description, and “the process of translating the content of an image into verbal expressions poses significant challenges to concept-based indexing“(Matusiak, p. 285). The subject analysis of a language resource can be defined as a process of establishing the subjects of a document. During the process of subject analysis the most suitable subject headings (or descriptors) for the comprehensive description of its content are found. Such analysis is not an easy task. The question is which features of documents should be considered in the subject analysis? (Albrechtsen, 1993). Visual materials may require a completely different approach. Certain features, like title, author, appearance, can be easily identified and used in the description as access points. Furthermore, any image can be differently perceived and interpreted by various groups of users, who may have varying competencies and specific needs. First of all, in thinking about image indexing, it is necessary to ask if the description of the subject and content of an iconographic document is at all possible. If so, how should it be described? What is the subject of such a document? What is it about? How should works of art be interpreted and what should be included in their description? What aspects of images may be interesting to users? 3 The problem of analyzing the meaning of a work of art has been discussed by the art historian, Erwin Panofsky, who defined three levels at which a work of art could be described. He suggested that there might be three strata of the meaning of an art work. A work of art can be described on the pre-iconographic level, which consists of general aspects – the primary or natural subject matter; the iconographic level, which encompasses concrete aspects – the secondary or conventional subject matter; and the iconological level, which includes symbolic, abstract aspects – the intrinsic meaning or content (Panofsky, 1962). These three strata of interpretation (pre-iconographic description, iconographic analysis and iconological interpretation) require specific skills from the interpreter, namely practical experience, the knowledge of resources, themes and concepts as well as synthetic intuition (Panofsky, 1962). Panofsky’s scheme was enriched by Sara Shatford, who also adapted her ideas to image indexing (Shatford, 1986). She renamed Panofsky’s strata as generic, specific and abstract and subdivided each of these areas into four aspects, each of which forms an answer to one of the following questions: Who?, What?, Where?, When?. In this way she created a model of description that encompasses all the aspects of a picture. According to the Panofsky/Shatford model, there are three levels of analysis and description: -pre-iconographical (generic things, such as woman, flower, building), -iconographical (specific things, such as Salome, rose, temple), and - iconological (symbolic or abstract things, such as heaven, love, New Jerusalem). For example, a flower may be depicted as an element of inanimate nature, simply for its beauty, and it may also appear as a symbol or an element of an iconographical program. Shatford also introduced the distinction between OF (what a picture consists of) and ABOUT (what a picture is about). The OF/ABOUT paradigm was a critical change that Shatford made to Panofsky’s theories, bringing iconography out of the realm of Renaissance art and into the broader realm of images in general. The process of indexing is connected with the concepts of ofness and aboutness and isness. Aboutness is the more widely used one of the two terms. It focuses on what is conveyed in a document, what it is about, what its content, subject or theme is. Aboutness depends on the 4 interpretation of the set themes, motifs, actions and events in a work. It is one of the many terms used for expressing certain features of a text or document (features different from the form and the so called description data). Aboutness (and other terms with the same meaning), as a vital element of the organization of knowledge and information retrieval, has been discussed by many researchers (see Hjørland, 2001). Aboutness is a category that can be used for both language and non-language resources, while the other category – ofness – is a term which only applies to the analysis of pictures. Ofness refers to the elements that a picture consists of. The concepts of aboutness and ofness used in picture description are based on Panofsky’s theory about the three strata of meaning in a work of art. Aboutness and ofness are characteristic of the pre-iconographic and iconographic levels of description. Panofsky’s third stratum – the iconological level of description – refers to the interpretation of the inner meaning or content of a work of art (Panofsky, 1962; Shatford, 1986; see also Zeng, Žumer, & Salaba, 2010). Isness is another concept which appears in the process of indexing. It tells us what the resource is. Very often this element is close to genre/form terms. The isness of a resource can be physical or intrinsic, e. g. textbook, DVD, poetry, libretto, etc. (Ingwersen, 2002). Core principles for describing and indexing images have been discussed and agreed upon at the international level by art historians and information professionals (with the predominant role of American experts). The fundamental set of rules and recommendations in this area is known as CCO, Cataloging Cultural Objects. A Guide to Describing Cultural Works and Their Images (Baca et al. 2006). It enumerates the mandatory elements of description, such as: 1. Object Naming, 2. Creator Information, 3. Physical Characteristic, 4. Stylistic, Cultural and Chronological Information, 5. Location and Geography, 6. Subject, 7. Class, 5 8. Description. This is a general frame, the basic standard of data content, but the choice of appropriate indexing tool and the decision about indexing policy must be taken by each cataloguing agency respectively according to its collection profile and its users’ needs. There are two crucial questions to be answered while deciding about images indexing: - what level of description should be adapted? What is our intention: to express what the image represents (the OF aspect in both a specific and generic sense), or what the image is about (the ABOUT aspect), or to index both of them? - what indexing tool (tools) could be used successfully? Controlled or uncontrolled vocabulary or both of them? Internationally approved thesaurus or local information language? While creating an image description, the cataloguer may consider the formal aspects of the object (such as the medium, the technique and/or the material) and other categories that are not directly related to the content of an image. These may include: - type of document/field of art (photography, engraving, drawing, painting) - technique/material (collage, oil on canvas, woodcut, ivory carving, photogravure) - dating (17 century, 1201-1300, the end of 15 century) - culture, epoch, art movement (Dutch art, Ming Dynasty painting, Art Deco) However, the indexer’s main task is to specify content features and to create the description of the “content” of a document. The basic elements of content include, among others: - objects and actions (a girl, a cottage, a boat, a meadow, a bird, sowing) - type of picture (sketch, self-portrait, still life, veduta, seascape) - scene or iconographic type (Adam and Eve, Madonna Lactans, Last Supper, Cupid and Psyche, Buddha Amitabha). Subject analysis and the description of “content” of iconographic documents are sources of numerous problems (Svenonius, 1994; Roberts, 2001). Establishing and defining the subject and meaning of an image may be problematic and identifying the objects is often difficult. Furthermore, the indexing of multifaceted, often allegoric or symbolic images, which are interpreted on many different levels, presumes a certain degree of knowledge of 6 iconography (Schroeder, 1998; Jacobs, 1999). Abstract images, images related to a foreign culture, and images created in different epochs each may contain elements of unknown meaning, indecipherable symbols and gestures, are another source of problems. Finally, the circumstances in which the work was created (usually only known to the author of the work) may influence the interpretation of an image. The most difficult and problematic task is to express the highest level of meaning, which is the third level of Panofsky/Shatford model: iconology/interpretation. Only specialists or very experienced indexers will recognize some signs and symbols and, by reading between the lines, reconstruct the highly sophisticated iconographical program, e.g. “an image of a grey brick wall is about socialism” (Neugebauer, 2005, p.5). As Herbert Read noted “What we really expect in a work of art is a certain personal element – we expect artist to have, if not a distinguished mind, at least a distinguished sensibility. We expect him to reveal something to us that is original – a unique and private vision of the world.” (Read, 1968, p. 27) Unfortunately, very often we are unable to name and express what is important, unique and original in this vision, its sense remaining inaccessible or unexpressed. In addition to the general problems with indexing of images, there are some questions connected with the rules governing the creation of the authorized access points and with the usage of the subject authority file. In this context a few specific problems can be enumerated: - usage of detailed description vs. assignment of broader concepts, - relation with authority file and with general indexing policy - consistency or independence? - descriptive cataloguing and subject indexing – complementarity or independence? Detailed description vs. broader concepts It is obvious that the first and second level of images content should be indexed, but each cataloguing institution has to make a choice between assignments of strictly adequate or broader concepts. It is a crucial decision and not an easy one. 7 For example, Caravaggio’s Basket of Fruits may be indexed using single term referring to the art genre – “Still life”. For advanced iconographic researches, a detailed description (“apple; fig; grape; pear; basket”) could be more useful. A print which presents over twenty portraits of famous Italian singers may be indexed with subject heading “Singers” (with geographical subdivision “-Italy”) and general subject designation “Portrait”. Is it enough? The other option is to enumerate, as additional subject access points, all the names of the fifty depicted person: “Agujari, Lucrezia (ca 1743-1783); Amicis, Anna Lucia de (ca 1733-1816); Amorevoli, Angel (1716-1798); Ansani, Giovanni (1750-1815)” etc. Which of these solutions is better? Which of them could satisfy the need of various audiences and maximize research results? Assignment of broader concepts facilitates the indexing – it is easier and less timeconsuming and the information about described objects is not dispersed. On the other hand, in order to give the users the complete iconographic information and comparative material for studies, all objects identified in the picture should be accepted as subject access points. Another important question which should be answered before making decisions is: “Will your system link a specific term to its broader contexts and synonyms in an authority file? If not, you should include important broader contexts and synonyms in the work record.” (Baca et al. 2006) Relation with authority file and with general indexing policy - consistency or flexibility? If the cataloguing institution provides authority control, the main problems are how the detailed terms describing images could be integrated into an indexing system exploring a local subject authority file and how to ensure consistency in indexing policy. For example, NL of Poland has been using, for more than thirty years, its own indexing tool – JHP BN (National Library of Poland Subject Headings). All collections are indexed using this controlled vocabulary and according to the general indexing guidelines. The indexing language is able to provide many generic terms, but for detailed descriptions of images the subject authority file should be extended by thousands of terms corresponding to types of objects and architecture, materials, types of people and activities, physical attributes, 8 associated concepts etc. Most of these specific terms could occur only in the images description. Problems with image indexing are clearly evident also in the case of architectural objects or persons, for which names usually come from the authority file. One should ask, however, if all the aspects of iconographic material have been considered and whether current solutions are adequate for the description of images and suited to the expectations of users. One of the most serious problems in identification is determining what the image presents and when the image was created (who owned the object at that time, what the object looked like, what its function was). There is also the question of what version of the name to choose – e.g. the name in the language of the country in which the object is currently located or the name the object had at the time the image was created? It is also necessary to decide whether to make the heading appropriate for the image (refer to the time when the image was created and the name that the object then had) or to use the latest (current) name of the object with a suitable chronological subdivision. This is connected with the rules of using proper names of objects within the file and the way such names function in the catalogue – should headings be appropriate for objects or should one name be selected and used consistently although it may not be suitable for all the different images of the object? This has significant influence on the process of searching for information in the catalogue. If the heading appropriate for the object is used, users are more likely to find exactly what they are searching for, but the entire context is lost, information is dissociated from the object, and the material becomes more difficult to find. Adoption of the latter solution, however, will lead to creating inadequate descriptions, while the material is overly concentrated. A similar problem refers to personal names: whether the heading in the authority file refers to the latest name used by a person or to the most frequently used name. A print representing the king of Poland Henryk Walezy and his court would be indexed with the name “Henry III (king of France)”, which was his latest and most frequently used name, preferred in the authority file. Descriptive cataloguing and subject indexing – complementarity or independence? 9 There are elements of subject description that sometimes appear as an element of descriptive cataloguing (like title, date, type of representation stated in the title). Some titles include exact information about the content. For example: “White roses, chrysanthemums in a vase, peaches and grapes with a white tablecloth” painted by H. Fantin-Latour (1876). Should this information be repeated as subject terms? The CCO rules state that “if terms repeat or overlap terms applied to other elements such as Title or Work Type, a thorough description and indexing of the subject content should be done separately in the Subject element.” The cataloguing institution, taking into account the technical aspects of searching and retrieval, should consider the pros and cons and make its own decision regarding cataloguing policy. The popular method of image indexing is to provide the basic bibliographic data, such as name of creator, title, date, material, measure, and to support the image with some descriptive text (Neugebauer, 2005). It is the current practice of several museums showing their collections both in traditional publications and accessible on a Web site. In the libraries communities, however, the tradition of indexing based on controlled vocabularies organized in authority files is stronger. There is no vocabulary standard that would satisfy the needs of all cultural heritage institutions. Regarding subject indexing of images, several tools and methods may be taken into account: - controlled vocabulary (thesauri, subject headings, or classifications) – terms expressing both depicted objects and form/genre/type of document taken from an authority file may be used as elements of pre-coordinated strings (according to local indexing rules) or as single subject access points Libraries do not use all the existing indexing tools for the description of iconographic documents. Some of the tools (such as subject headings) are too general to enable the description of certain elements of the iconographic aspect of images; others, such as the Library of Congress Thesaurus for Graphic Materials (TGM), the Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT), and Iconclass, encompass elements connected with both the technique of creation and the iconography of objects (Baca 2002; Harpring 2010). 10 Numerous libraries have indexed their images collection using thesauri and subject headings. The great picture collections of the Library of Congress are indexed using several indexing tools: Library of Congress Subject Headings and terms derived from specialized thesauri such as TGM and AAT. This practice confirms that even the most detailed vocabulary of subject headings is inadequate to index the extensive semantic layers of images or issues related to the formal aspect of the work. Similarly, for indexing collections of images the Bibliothèque nationale de France use its subject headings language RAMEAU to a very limited extent. The headings are completed with keywords taken from thesauri or lists dedicated to this type of collection. - uncontrolled vocabulary – keyword created by indexers without semantic control or tags (folksonomy) created both by the inexperienced users and experts Keyword indexing is not very popular in the libraries, and also museums seem not to be interested in practicing free keywords assignment. There are, however, some projects in the museums community exploring the advantages of social tagging in indexing work of art and artifacts. The best known among them is “Steve. The Museum Social Tagging Project”: tags assigned by digital museum visitors have completed museums’ formal descriptions of works, created by art historians or other specialists. There is no limit to the number of terms that may be assigned per image; some of the presented works are tagged with more than fifty tags. “Steve project” shows all the disadvantages of social tagging: redundancy in terms, inconsistency of spelling, inappropriate, meaningless and subjective expressions. There are, nevertheless, a lot of additional access points which are relevant and constitute added value in images retrieval. - notes containing the free-text description of the image, additional data about it and scientific commentary – created by indexers This solution is hardly used in the libraries but well-liked by art historians which have no experience (or very little experience) with controlled vocabulary systems. When analyzing a variety of principles, rules and tools, one sentence comes to mind: “A picture is worth a thousand words”. It is the statement that may frustrate all librarians 11 looking for an effective model for images indexing. It is also the great challenge we have to undertake. Instead of the conclusion: a modest proposal Looking for a model of image description, we analyzed several standards and practices of some large libraries and museums. CCO is the most complex and appreciated among data content standards. Our intention is to respect these guidelines as much as possible. Nevertheless, it must be taken into account that images are a minor part of the NL’s collection and must be recorded and indexed consistently with common cataloguing rules. All digitized images available at the National Digital Library Polona are primarily described in the NL’s OPAC and the bibliographic record created in MARC21 format is linked to the metadata record in the Dublin Core scheme used in the digital library. Subject terms dedicated to images indexing must be stored in the common subject authority file. The local indexing language JHP BN (National Library of Poland Subject Headings) is used as our standard for subject data value and the use of terms from other vocabularies is excluded. When indexing images we intend to exploit JHP BN controlled vocabulary as subject terms, genre/form term or keywords, recorded in several MARC21 fields: 600-651 subject terms (controlled vocabulary) Terms should be specific to the overall scope of the document (what the image is “of”), including names of persons and corporate bodies, names of places, events, objects. Each real object and each scene or iconographic type, if identified, should be indexed. Generic and specific things which are the basic elements of the content should also be enumerated. Secondary elements may be captured as additional subject access points. If the content is multi-layered or not consistent, only a genre/form term is assigned. 655 genre/form term (controlled vocabulary) Terms should express the type of document (e.g. painting, drawing, photography, print), technique (e.g. etching, watercolor, gouache, albumen print) and object genre (e.g. portrait, landscape, seascape, city view, genre scene, mythological scene, allegory). 12 653 additional subject access points (both controlled and uncontrolled terms) Terms related to secondary, subordinated or less important content elements, e.g. objects depicted in the background and as staffage. It is also possible to give a broader context and synonyms of specific terms used both as subject and genre/form terms. and 520 note/summary, that may contain free-text description, including the meaning, purpose or function of image (what the picture is “about”). It may also include information about the style or period, material, form and composition etc. The proposal will be discussed with the Polish professionals responsible for images cataloguing and indexing and with the art historian community. In our opinion, the scheme presented above is acceptable for both library and museum experts. It is partly analogous to the concept of description implemented in the first Polish digital museum2. A consistent documentation of objects collected in cultural heritage institutions would make the resources of images more accessible and would serve successfully as a basis for scientific research and education. 2 http://cyfrowe.mnw.art.pl 13 Examples (For make examples more comprehensible English equivalents of JHP BN subject terms are given) Example nr 1. 100 1 Hiszpański, Stanisław |d(1904-1975). 245 10 Odwieziony we śnie na Itakę |h[Dokument ikonograficzny]. 246 13 |iZnane także jako:|aOdyseusz repatriowany 260 |c1964. 300 1 rys. :|btusz-pędzel, akwar., na szkicu ołówkowym ;|c32,5x23 cm. 520 Odysseus, fast asleep in a hidden harbor on Ithaka. Athena is keeping vigil over him. In background the sea and an ship, probably Phaeacian. 600 Odysseus 653 Homerus. Odusseia; Athena; Ithaka; sea; ship; harbor; man asleep; Greek mythology; Greek goddess; gorgoneion 655 Illustration 655 Watercolour 655 Coloured drawing 14 Example nr 2. 100 1 Adam, Jean Victor|d(1801-1866). 245 10 Haquet et traîneau de brasseur|h[Dokument ikonograficzny] /|cV. Adam del. 260 [À Paris] :|bLith. de C. Motte,|c[1830]. 300 1 graf. :|blitogr. ;|ckompoz. 12,4x20,5 cm, z napisami 16x22 cm. 520 This print is probably a part of a larger series entitled 'Voitures'. At center of composition, a brewer's dray and sledge loaded with barrels; at right, in front of a café with an awning, a man on horseback and a man holding a barrel; beyond at left, buildings and a small crowd of soldiers; 653 road; horses; coffeehouse; barrel; delivery; awning; carriage 655 Genre scene 655 Lithograph 655 Print 15 Example nr 3. 100 1 Drzewiecka, Helena. 245 10 [Bukiet kwiatów]|h[Dokument ikonograficzny]. 260 |c[1815-1820]. 300 1 rys. :|bgwasz, pap. brązowy ;|c33,6x25,6 cm. 650 Flowers 653 pansy; iris; lily; ancolie; rose; bouquet 655 Gouache 655 Painting 16 Example nr 4. 100 1 Rzewuski, Walery|d(1837-1888). 245 10 [Helena Modrzejewska jako Małgorzata w spektaklu "Faust" Johanna Wolfganga Goethego]|h[Dokument ikonograficzny] / |c[Walery Rzewuski]. 260 |c[1869]. 300 1 fot. :|bodb. albuminowa ;|c9,1 x 5,5 cm. 520. “Gretchen in the cathedral tormented by an Evil Spirit” or “Gretchen refuses to escape from prison” (?). Photograph has been taken in Rzewuski atelier after the spectacle in the Stary Teatr in Kraków 13 or 14.02.1869 600 Modrzejewska, Helena|d(1840-1909) 653 Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von(1749-1832).Faust; Actress; Polish theatre; Margaret; Gretchen 655 Photograph 655 Portrait 655 Albumen print 17 REFERENCES Albrechtsen H. (1993). Subject Analysis and Indexing: From Automated Indexing to Domain Analysis. The Indexer, 18(4), 219–224. Baca, M. (ed.). (2002). Introduction to Art Image Access: Issues, Tools, Standards, Strategies. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute. Retrieved from http://www.getty.edu/research/publications/electronic_publications/intro_aia/index.html Baca, M., Harpring, P., Lanzi, E., McRae. L & Whiteside, A. (2006). Cataloging cultural objects: a guide to describing cultural works and their images. Chicago: American Library Association. Chu, C. M., & O’Brien, A. (1993). Subject Analysis: The First Critical Stages in Indexing. Journal of Information Science, 19, 439-454. Harpring, P. (2010). Introduction to Controlled Vocabulary: Terminology for Art, Architecture and Other Cultural Works. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust. Retrieved from http://www.getty.edu/research/publications/electronic_publications/intro_controlled_voca b/index.html Hjørland, B. (2001). Towards a Theory of Aboutness, Subject, Topicality, Theme, Domain, Field, Content. . . and Relevance. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52(9), 774–778. Ingwersen, P. (2002). Cognitive Perspectives of Document Representation. In H. Bruce, R. Fidel, P. Ingwersen & P. Vakkari (Eds.) Emerging Frameworks and Methods: Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science (CoLIS 4) , pp. (285-301). Greenwood Village, Colo.: Libraries Unlimited. Jacobs, C. (1999). If a Picture is Worth a Thousand Words, then…. The Indexer, 20(3), 119121. Jansen, B. J. (2008). Searching for Digital Images on the Web. Journal of Documentation, 64(1), 81-101. 18 Jörgensen, C. (1999). Access to pictorial material: a review of current research and future prospects. Computer and the Humanities, 33(4), 293-318. Jörgensen, C. (2003). Image retrieval: theory and research. Lanham, MD & Oxford: Scarecrow Press. Lancaster, F. W. (1998). Indexing and Abstracting in Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. London: Library Association Publishing Matusiak, K. (2006). Towards User-Centered Indexing in Digital Image Collections. OCLC Systems and Services, 22(4), 283-298. Neugebauer, T. (2005). Image Indexing. Photography Media Journal, March. Retrieved from: http://www.photographymedia.com/article.php?page=1&article=AImageIndexing Panofsky, E. (1962). Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Harper & Row. (first ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1939). Read, H. (1968). Meaning of Art. London: Faber. Roberts, H. E. (2001). A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words: Art Indexing in Electronic Databases. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52(11), 911-916. Schroeder, K. A. (1998). Layered indexing of images. The Indexer, 21(1), 11-14. Shatford, S. (1986). Analyzing the Subject of a Picture: A Theoretical Approach. Cataloging. & Classification Quarterly, 6(3), 39-62. Springer, M., Dulabahn, B., Michel, P., Natanson B., Reser D., Woodward D., & Zinkham, H. (2008). For the Common Good: The Library of Congress Flickr Pilot Project. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/flickr_report_final.pdf Svenonius, E. (1994). Access to nonbook materials: the limits of subject indexing for visual and aural languages. Journal of the American Society of Information Science, 45(8), 600-606. 19 Zeng, M. L., Žumer, M., & Salaba, A. (Eds.). (2010). Functional Requirements for Subject Authority Data (FRSAD). A Conceptual Model. München: K. G. Saur. 20