decent bargaining

advertisement

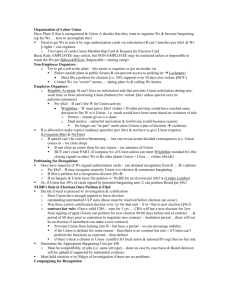

Chapter 15 LABOR LAW Practice Test 1. Power, Inc., operated a surface coal mine in central Pennsylvania. Financial losses led it to lay off a number of employees. After that, several employees contacted the United MineWorkers of America (UMWA), which began an organizing drive at the company. Power’s general manager and foreman both warned the miners that if the company was unionized, it would be shut down. An office manager told one of the miners that the company would get rid of union supporters. Shortly before the election was to take place, Power laid off 13 employees, all of whom had signed union cards. One employee, who had not signed a union card, had low seniority but was not laid off. Later, one of Power’s lawyers told several miners that anyone caught helping the 13 laid-off workers by contributing to a union hardship fund would “be out there looking for help from somebody else.” Comment. Each of the acts described was an unfair labor practice in violation of §8 of the NLRA. Workers have the right to organize and join a union. Although management is entitled to advocate vigorously against unionization, it may not threaten employees or interfere with the organizing effort. The NLRB found the employer's interference to be extreme, and it issued a bargaining order. The court of appeals affirmed. Power, Inc v. NLRB, 40 F.3d 4096 (D.C. Cir. 1994). 3. Q-1 Motor Express was an interstate trucking company. When a union attempted to organize Q-1’s drivers, it met heavy resistance. A supervisor told one driver that if he knew what was good for him, he would stay away from the union organizer. The company president told another employee that he had the right to fire everybody, close the company, and then rehire new drivers after 72 hours. He made numerous other threats to workers and their families. Based on the extreme nature of the company’s opposition, what exceptional remedy did the union seek before the NLRB? Based on the extreme nature of the company’s opposition, the union sought an order to bargain. An administrative law judge found that the company had committed a ULP by interfering with the organizing drive. The NLRB affirmed, issued a bargaining order, and appealed to the court of appeals for enforcement. The court enforced the Board’s bargaining order. Q-1 had threatened to fire some employees based on their organizing efforts, and did fire others for the same reason. Non-union employees had never been fired. The threats and intimidation were persistent and pervasive, in blatant violation of section 8 (a). 5. Gibson Greetings, Inc., had a plant in Berea, Kentucky, where the workers belonged to the International Brotherhood of Firemen & Oilers. The old CBA expired, and the parties negotiated a new one, but were unable to reach an agreement on economic issues. The union struck. At the next bargaining session, the company claimed that the strike violated the old CBA, which had a no-strike clause and which stated that the terms of the old CBA would continue in force as long as the parties were bargaining a new CBA. The company refused to bargain until the union at least agreed that by bargaining, the company was not giving up its claim of an illegal strike. The two sides returned to bargaining, but meanwhile the company hired replacement workers. Eventually, the striking workers offered to return to work, but Gibson refused to rehire many of them. In court, the union claimed that the company had committed a ULP by (1) insisting the strike was illegal and (2) refusing to bargain until the union acknowledged the company’s position. Why is it very important to the union to establish the company’s act as a ULP? Was it a ULP? The strike was initially over pay and was thus an economic strike. If the company committed a ULP by refusing to bargain until the validity of the strike was resolved, then it converted the dispute into a ULP strike. In that case, all striking workers would be entitled to their jobs back, even if it meant laying off replacement workers. But the court ruled that the company had not committed a ULP. Gibson claimed in good faith that the strike was illegal. The strike remained an economic one, and the striking workers were not guaranteed their jobs back (though they had to be rehired without discrimination if openings appeared). Gibson Greetings v. NLRB, 53 F.3d 385 (D.C. Cir. 1995). 7. Eads Transfer, Inc., was a moving and storage company with a small workforce represented by the General Teamsters, Chauffeurs and Helpers Union. When the CBA expired, the parties failed to reach agreement on a new one, and the union struck. As negotiations continued, Eads hired temporary replacement workers. After 10 months of the strike, some union workers offered to return to work, but Eads made no response to the offer. Two months later, more workers offered to return to work, but Eads would not accept any of the offers. Eventually, Eads notified all workers that they would not be allowed back to work until a new CBA had been signed. The union filed ULP claims against the company. Please rule. The union is correct. Eads locked out its employees by refusing to allow them back to work. A lockout is a legitimate weapon with which a company may apply economic pressure on a union to force agreement on a CBA. But the company must notify the union of the lockout before it begins, so that the union understands the position and may bargain or respond accordingly. Without such notice, the lockout doesn't serve to bring the parties together, which is the purpose of the NLRA. Eads Transfer, Inc. v. NLRB, 989 F.2d 373 (9th Cir. 1993). 9. Fred Schipul taught English at the Thomaston (Connecticut) High School for 18 years. When the position of English Department chairperson became vacant, Schipul applied, but the Board of Education appointed a less senior teacher. Schipul filed a grievance, based on a CBA provision that required the Board to promote the most senior teacher where two or more applicants were equal in qualification. Before the arbitrator ruled on the grievance, the Board eliminated all department chairpersons. The arbitrator ruled in Schipul’s favor. The Board then reinstated all department chairs—all but the English Department. Comment. The Board of Education committed a ULP by terminating the position. The Board has a continuing duty to bargain in good faith–even after a CBA has been signed. If issues arise that require bargaining, or a grievance under the CBA, the Board must act in good faith. Here, the Board terminated a position to evade an arbitrator's award made pursuant to the CBA. That is a ULP. The court ordered the Board of Education to restore the job to Schipul. Board of Education of Thomaston v. State Board of Labor Relations, 217 Conn. 110, 584 A.2d 1172 (1991). 11. ETHICS This chapter refers in several places to the contentious issue of subcontracting. Make an argument for management in favor of a company’s ethical right to subcontract, and one for unions in opposition In favor of management’s ethical right to subcontract: The company exists to make a profit. Shareholders expect management to do whatever is necessary and legal to produce maximum profits. Chapter 15 Labor Law 229 Among other things, management must insure that the company is financially viable. If production costs are so high that the company will be driven out of business, neither shareholders nor workers will benefit. It is management’s job to produce goods as cheaply as possible, and to take the work wherever that can be accomplished. If other workers are willing to do the same work more cheaply than high-cost union labor, then subcontracting is not only ethical but essential. Opposed to management’s ethical right to subcontract: This is a prosperous country because for decades working men and women have devoted their lives to hard work on behalf of its companies. A corporation has no right to betray that loyalty by moving work to poorer areas. There is nothing wrong about workers earning a decent wage, one high enough so that they can afford to feed and clothe families and perhaps save for a child’s education. The reason that some workers are willing to work for dirt-cheap wages is that they have no union to represent them. Shifting work from unionized parts of the country to non-unionized regions, or to developing countries, betrays the spirit of the NLRA.