Physiology of Breathing

advertisement

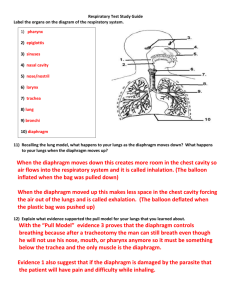

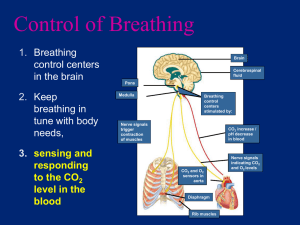

Physiology of Breathing Please read Coulter pp.67-137 in conjunction with these notes. Hatha Yoga Pradipika: “Just as lions, elephants and tigers are gradually controlled, so the prana is controlled through practice. Otherwise the practitioner is destroyed.” Respiratory System The lungs are composed mostly of air – 50% after full exhalation and 80% after full inhalation. A membrane covers the lungs which can be thought of as a blown-up balloon filling the rib cage. The balloon however is NOT tied at its neck but open. The reason the lungs and its membrane don’t simply just deflate is because of the natural elasticity which allows the lungs to expand and contract as the rib cage expands and contracts. There is a vacuum between the membrane surrounding the lungs and the thoracic cavity in which they lie, known as the pleural cavity, which means the lungs are always held tightly against the chest wall. Movements of the chest are followed by movement of the lungs. Expansion of the chest also expands the lung volume, creating a partial vacuum i.e. lower pressure than atmospheric, and air moves in to the lungs. Conversely, contraction of the chest volume also diminishes the lung volume, forcing air out of the lungs. Muscles of Respiration Inhalations can only take place as a result of muscular activity. Exhalations take place due to elasticity of lungs making them smaller. Consider that the last breath you will take will be an exhale. Similarly the first breath you take is an inhale. The entire life is encompassed between that first inhale and final exhale. There are three main sets of muscles used in breathing: 1) The Intercostals – there are 2 sets of these: The external muscles run between the ribs and lift and expand the rib cage for inhalation. The internal muscles run at right angles to the externals and pull the ribs closer together and down and in for exhalation. The externals also act to prevent the rib cage collapsing inwards when the diaphragm moves downwards to create the vacuum that draws air into the lungs. 2) The Abdominal Muscles. These work mainly in deep and forced exhalation. They press the abdominal wall inwards, the abdominal organs then push up against the diaphragm. In combination with the internal intercostals, this rapidly decreases the size of the chest cavity and pushes air out the lungs. See Kapalabhati later for a practical example of this action. 3) The Diaphragm – A domed sheet of combined muscle and tendon which spans the entire torso and separates the chest cavity from the abdominal cavity. Its rim is attached to the base of the rib cage and to the lumbar spine in the rear. It looks a bit like an umbrella, with its lower rim attached all round the lower rim of the rib cage. See diagram in Coulter p. 79. There are further attachments to the lumbar spine. The diaphragm is therefore able to move the base of the rib cage and the lumbar spine. During inhalation, the dome of the diaphragm flattens creating a slight vacuum which draws air into the lungs. On exhalation, the dome is drawn upward, and air moves out of the lungs. In relaxed breathing the diaphragm acts like a piston, moving up and down within the chest wall. This can be seen if lying down, where the relaxed abdomen moves up and down with the breath. Here the breathing is carried out entirely by the diaphragm – sometimes called abdominal breathing. Contrast this with diaphragmatic breathing. This is achieved by holding some tension in the abdominal wall which impedes the downward movement of the diaphragm. Instead, the diaphragm acts on the rib cage, spreading the base of the rib cage to the front, to the rear and to the sides. This expansion of the rib cage draws in air to the lungs. This has been referred to as “thoracodiaphragmatic breathing” and is illustrated in p.137 (Coulter), as opposed to “abdominal” or “abdomino-diaphragmatic” breathing – as illustrated on p. 136 (Coulter). The former is important in Astanga Yoga, as we’ll discuss later on. A good way to feel thoraco-diaphragmatic breathing is to do the cobra, arms clasped behind back, with all the leg muscles tightened – then the movements of the diaphragm are translated into expansion of the rib cage, which is felt as a lifting of the torso on an inhalation. Nervous System What controls the muscles of respiration? It is controlled by the somatic nervous system – which controls all skeletal muscle activity as well as conscious sensations. The diaphragm is innervated by the phrenic nerves – these have their cell bodies in the spinal cord in the neck region (C3-C5). The intercostals and abdominals are innervated by other nerves originating in the spinal cord. The autonomic nervous system (which runs without our conscious control) feeds into the somatic system, continually adjusting the respiratory centres for changes in its surroundings e.g. decreased O2 levels, increased activity and so on. Different methods of breathing can have an impact on functions normally considered to be under unconscious control. The obvious example is how quiet relaxed breathing slows the heartbeat and reduces blood pressure, and gives a sense of calm. In other words, through breathing techniques we can influence otherwise unconscious functions. This is exploited in yogic pranayama. Exercise – simply exhaling twice as long as inhaling, without stress, will slow down the heart. Hypoventilation – increased CO2 levels, decreased O2 levels, Hyperventilation – increased O2 levels, decreased CO2 levels, in alveolar, venous, arterial and cellular sites. Hypoventilation is practised in yoga using breath retention (Kumbhaka), where CO2 levels are deliberately raised. Hyperventilation will increase O2 in the blood, but this is not harmful. It also decreases CO2 in the blood, which can in extremes lead to constriction of the small arteries and arterioles of the brain and spinal cord, which is obviously not desired. Methods of Breathing 1) Thoracic – any exercise which encourages the chest to expand – even just lifting the arms over the head as in the Sun Salutation. Matsyasana, the fish, is particularly good. Backbending while inhaling is also good, but harder. 2) Abdominal breathing (p. 136) - usually lying down. Awareness, and strength, can be developed in the diaphragm by placing a sandbag (3-15 pounds) on the abdomen. Bhastrika and Kapalabhati are abdominal breathing exercises (diagram p. 136) which require active and passive inhalations respectively, and active exhalations, without using the intercostal muscles. Both increase O2 and decrease CO2, and both can produce hyperventilation if taken to extremes. 3) Diaphragmatic – see p.137 of Coulter for illustration. In this breath, the abdominal muscles are held slightly taut (i.e. don’t let the abdomen rise on the inhale) and this encourages the rib cage to expand. It brings awareness to the centre of the body. It also affects posture – during this breath, the head moves back, the neck lengthens, the curve of the thorax decreases – i.e. the back flattens, and the lumbar lordosis increases. This is the breath used in Astanga Yoga, and encourages awareness of the navel as well as the use of Mula and Uddiyana Bandha. A detailed description of breathing will be covered in the 500 hour Teacher Training course. © Brian Cooper 2007