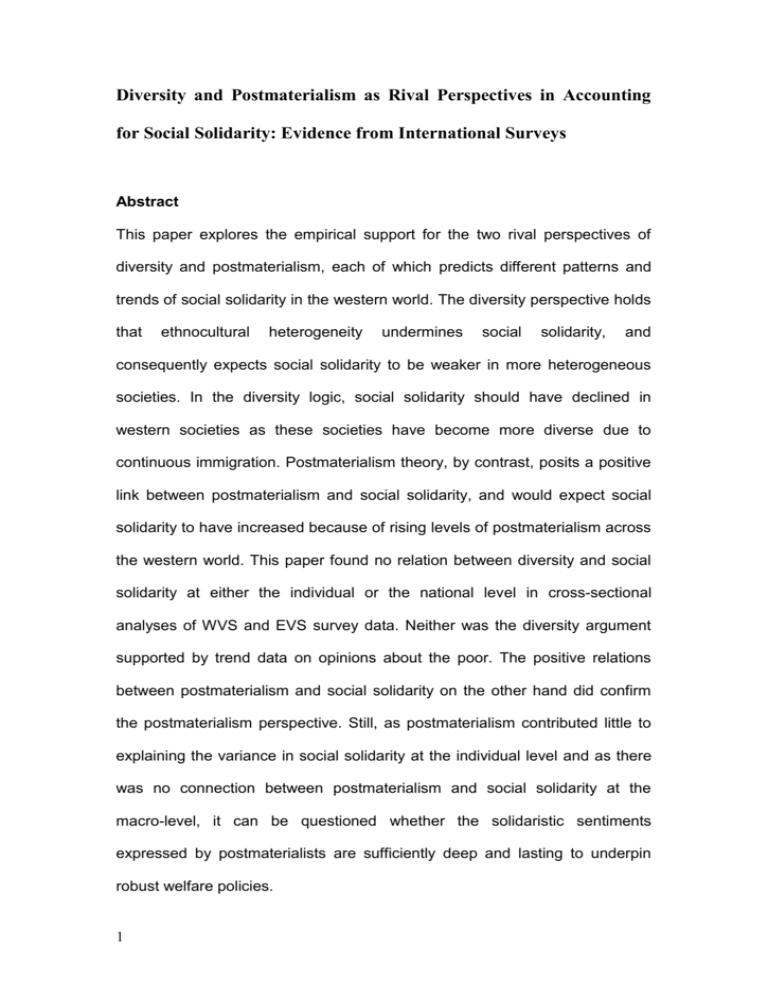

Diversity, postmaterialism and social solidarity

advertisement