The present study examines students` understanding of how works

advertisement

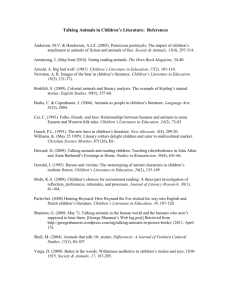

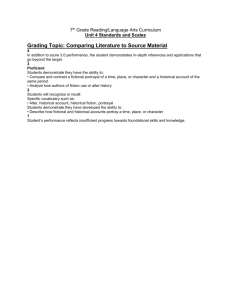

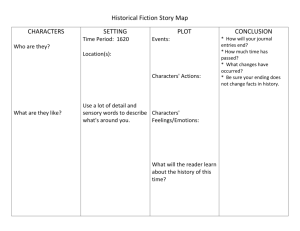

Present at Weber State University Undergraduate Research Symposium March, 2005 Conceptual Change in English Students’ Understanding of Fiction Robert Goodwin and Eric Amsel Weber State University Abstract The present study examines students’ understanding of works of fiction and how they can affect their beliefs about the real world. Students in Developmental, General Education, and Advanced English courses were given a questionnaire which assessed their beliefs about the truth of fictional information and its reality import. Most novice, but fewer advanced students, asserted that fiction is false and so can not alter one’s real world beliefs. The findings suggest that most novice students hold beliefs denying the possibility of Literary Truth, which become revised with literary training and experience Introduction Research on the psychology of fiction has shown that readers represent fictional information as compartmentalized mental structures called situation models. Situation models are psychologically distinguished from other mental structures which represent states of affairs that are real or believed to be real (Prentice & Gerrig, 1999; Zwaan, 1999). No psychological research has examined when and how fictional information is used intentionally to understand the real world. Understanding how literature can provide a perspective on reality is central to the concept of Literary Truth, which holds that literature captures a reality too concrete to be captured by abstract scientific and philosophical discourse (Park, 1984). Gerrig and Prentice (1999) identified the paradox implicit in the concept of Literary Truth. On the one hand, Literary Truth involves acknowledging that authors of fiction invent facts in constructing a plot. On the other hand, the concept also implies that information presented in fictional works can alter real world beliefs. The paradox is resolved when it is recognized that fiction refers to reality indirectly and analogically, as exemplified in parables, rather than directly. To assess students’ appreciation of the concept of Literary Truth, Prentice and Gerrig (1999) posed college students four questions about the nature and reality import of literary works. The results showed that students embraced both sides of the paradox, but were more agnostic (neither accepting nor rejecting) about whether all fictional information is invented and false. The present research explores whether there are changes in students’ understanding of Literary Truth with literary training and experience. The same four questions used by Prentice and Gerrig (1999) were given to students in Developmental (Eng 960), General Education (Eng 1000- to 2000-level), and Advanced English (Eng 3000-level and higher) courses. Students’ responses were analyzed along with self-reported ratings of their literary background and skills. Method Participants The sample included 120 students (45% Male, 55% Female) in lower- and upper-division English Courses. Participants averaged 24 years of age and represented all student statuses: Freshman (23%), Sophomore (16%), Junior (21%), and Senior (38%). Three groups were formed. One group was composed of students in Developmental (900-level) and General Education (1000- and 2000 level) English courses (N=50), who reflected the most Novice in the discipline. Students in 3000- to 3500-level English courses (N=44) were also grouped together, reflecting an Intermediate status. The final group was composed of students with Advanced standing in the discipline and included students who were enrolled in English courses that were at the 3500-level and above (N=26). The three groups differed in a variety of expected ways, including age, number of English courses taken and their self-reported literary background and level of literary skill. The groups differed unexpectedly in sex, with more men in the Novice Group. Procedure Each participant completed a 15-minute questionnaire in the classroom. The questionnaire requested demographic information (age, sex, student status, and number of English courses completed) and a short literary history (their self-assessed literacy skills and their reading of various literary genres). The questionnaire included a number of questions for participants to complete. However, only the four questions posed by Prentice and Gerrig (1999) were analyzed, so only those will be described. Each of the following four questions were posed to participants who responded to each on a 7-point Likert scale: Strongly Agree (1), Neither Agree nor Disagree (4), Strongly Disagree (7). Information presented in fictional works (for example, novels or movies) can make me change my beliefs about the real world. (Change Belief) Information encountered in fictional works should not be assumed to be true of the real world. (Never True) Authors of fiction often invent facts that are inconsistent with the real world to fulfill the requirements of their plots. (Often Invented Facts) Information presented in fiction is invented by the author of the fictional work (All Invented Information). Results Participants’ responses to each question were analyzed using a statistical procedure (ANCOVA) which tested for difference in Question and Class Group, but equalized for differences between groups in age, sex, self-reported literary background and literacy skills. This procedure allows for differences in responses to be attributed to participants’ Group Status and not to other variables. Participants’ responses to the four questions were not statistically different from each other (Figure 1). However, a difference emerged when the average for each response was compared to the mean of 4 (neither believe nor disbelieve) on the scale. Change Belief (M=3.57) and Often Invent Facts (M=3.58) questions were significantly lower than a score of 4, suggesting a belief in the propositions (p<.01). However, the Invented Information and True of the Real World were no different from 4, suggesting that participants were agnostic (neither believing nor disbelieving). These results replicate those of Prentice and Gerrig (1999), who found that that students believed that fictional information can affect their beliefs, despite recognizing that authors of fiction often make up facts. However, the same students were agnostic about two more general claims: that fiction is true of the real world and that authors invent all information. The responses to questions were different in different Class Groups. Follow-up analyses showed that the Change Belief claim became more strongly believed and Invented Facts less strongly believed over the Class Groups, independent of sex, age, and perceived literary skills and background. Among the Novice group, the Change Belief claim was judged agnostically (neither believed nor disbelieved) but the Invented Facts claim was accepted (p<.05). The percentage of students who believed (ratings of 1 to 3) that authors make up facts and denied (rating of 5 to 7) that reading fiction can alter ones’ beliefs was caculated. A majority (53%) of Novice students adopted such a “False and Inert” view of fiction. A different pattern of beliefs emerged in the Intermediate Group. The Change Belief claim was believed (p< .05) but the Invented Facts claim was judged agnostically. Only a minority (26%) adopted the “False and Inert” view of fiction. Similarly, the Advanced group believed the Change Belief claim but were agnostic towards the Invented Facts claim. However, students in the Advanced group (M=3.01) more strongly believed the Change Belief claim than the Intermediate (3.48). Only a minority of students (23%) adopted the “False and Inert” view of fiction. Discussion The present study examined WSU English students’ appreciation of the concept of Literary Truth. Appreciating the concept involves endorsing the conflicting claims that the authors of fiction make up facts but that, despite its falsity, a work of fiction can alter a person’s real world beliefs (Prentice & Gerrig, 1999). Replicating Prentice and Gerrig (1999), WSU students believed the Changing Beliefs and Often Invented Facts claims about fiction but were agnostic regarding the more general Invented Information and True of the Real World claims. Students’ responses varied by their background in the discipline. Novice students (composed of Developmental and General Education English students) believed that authors of fiction make up facts, but were agnostic that their real world beliefs can be altered by fiction. A majority of these students viewed fiction as “False and Inert” by accepting the claim that authors make up facts and denying that their real world beliefs can be altered by fiction. Only a minority of Intermediate and Advanced English students embraced the “False and Inert” view of fiction. Instead, these students believed that their real world beliefs can be altered by fiction, but were agnostic about whether authors of fiction make up facts. Future research should assess whether the difference between novice and advanced students reflects the effect of training in the discipline or the self-selection as English majors of students with strong literary background and skills. The data suggest that students are actually learning the concept of Literary Truth. The reported results are controlled for students’ self-assessed literary background and skills. Nonetheless, follow-up research should longitudinally assess students through a series of English courses and measure changes in their beliefs about fiction and its reality import Acknowledgements The author and advisor would like to thank Drs. Russell Burrows, Ron Deeter, and Victoria Ann Ramirez for their help on the project. The feedback and comments of Drs. Deeter and Ramirez were particularly helpful in improving the nature of questionnaire and the design of the study. References Park, Y. (1982). The function of fiction. Philosophical and Phenomenological Research, 42, 416-424. Prentice, D. A., & Gerrig, R. J. (1999). Exploring the boundary between fiction and reality. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in Social Psychology (pp. 529-546). New York: Guilford. Zwaan, R. A. (1999). Situation models: The mental leap into imagined worlds. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 15-18. Figure 1: Overall responses to the four questions Strongly Disagree 7 6 5 Neutral 4 3 2 Strongly Agree 1 Change Belief True of Real World Often Invent Facts Questions Invented Information Figure 2: Responses to Change Belief and Often Invented Facts Questions, by Group Status Change Belief 6 Often Invent Facts 5 Neutral 4 3 2 Novice Intermediate Groups Advanced