The problem with Problems

advertisement

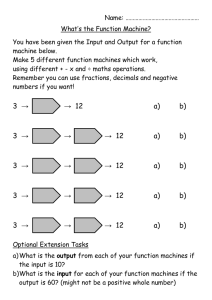

The problem with Problems Problem Solving has lain at the heart of the Maths Curriculum in Primary schools for many years and indeed the new curriculum 2014 places a greater emphasis on this element. However as it is all too easy to take the bland label of some supposed innovative issue and apply it in such a shallow fashion that it rips the heart out of what was truly intended as an excellent piece of curriculum thinking. I do feel that quality teaching of problem solving has all too often fallen into a deep, dark educational crevasse becoming morphed into something that is so diluted as to become unrecognisable in terms of good classroom practice. Word Problems or just words? Many have come to equate problem solving with those written questions found at the end of a given chapter in the Maths textbook. “Tom has 4 cats and 3 fish. How many pets does he have altogether?” The expected answer is 7, but this assumes that none of the cats have eaten any of the fish in which case it could be any number between 4 or 7. And here is the issue; problems should be set in the real world solving (surprisingly enough!) real problems. The clue is in the title, and yet so many word problems are simply a linguistic presentation of a standard algorithm. As Jo Boaler point out this leads to children developing a context for their Maths learning in an arena she calls “Mathsland”. She cites the following example: A pizza is divided into fifths for friends at a party. Three of the friends eat their slices but then four more friends arrive. What fraction should the following slices be divided into? No doubt there will be a technically correct numerically based answer in the teacher’s handbook that the teacher might use to mark the work in the evening. However, surely in the real world the answers are more likely to be those Jo Boaler offers namely that “if extra people turn up at a party more pieces are ordered or people go without slices” She concludes that “Over time children realise that when you enter “Mathsland” you leave your common sense at the door” The picture to the right illustrates this perfectly! The truth is that not all problems based on algorithms translated into words have meaning when solved mathematically. As Mike Askew points out the question; “If Henry VIII had 6 wives then how many did Henry IV have?” implies that he had 3 but this is another number problem with a one-way ticket to Mathsland. So bearing in mind that most of these problems lack all sense of reasons and reality what do children need to learn to successfully solve word problems in a classroom context. Well, the 1 first key skill is to realise what Ofsted noted that “Standard problems tend to be associated with exercises at the end of chapters, where pupils know the operation to use is, say, multiplication because the chapter was all about multiplication”. (Recent Research in Mathematics Education 5-16, Ofsted) The second survival strategy in the modern Maths classroom is to work out the likely operation from the context of the numbers. Mike Askew tells how he has a Chinese textbook which is written solely in Mandarin apart from the numbers, and whilst he does not read one word of mandarin he writes “I am confident that the problem involving 25 and 14 is most likely to be multiplication while the one with 3007 and 1896 is almost certainly subtraction.” Teaching in such contexts leads to a bland form of numerical understanding that sells children woefully short of the richness that number and Mathematics can offer. Ramya Vivekanandan analysed the PISA results for Maths in 2012. He showed that those children who relied purely or significantly on memorisation of formulaic strategies to solve calculations were consistently amongst the low achievers, whereas those students who focused on a breadth of Mathematics and developed the “Big Ideas” concepts were the high achievers. Jo Boaler in a lecture at Oxford University (18th December 2014) pointed out that the UK lay 64th out of the 65 countries for having the largest percentage of “memorisers”. Only Ireland scored lower. There was a consensus amongst the delegates that it is the UK’s obsession with testing that allows children to thrive on such bland, shallow word based material because it is that style of questioning that forms the basis of the tests at the end of Key Stage 2. So if it is true that many word problems are simply, as Mike Askew points out “calculations wrapped up in words” what is problem solving all about and does it, or should it, have such a prominent place in the Maths curriculum? What is Maths all about anyway? As with most issues related to education it increasingly seems to me that the key is to stand as far back from the issue as you can to allow the fullest perspective. Then when the macro elements are resolved in the mind, one can drill down to the micro elements of what makes up a scheme of work, a weekly plan, a daily lesson and down to the progress of individual children. Because our profession hinges around the classroom and its practice there is always the danger that teachers start with the question: What should I teach tomorrow? But this has no context if one has not engaged with the deeper and broader questions in the first instance. So what is “real mathematics?” Volumes have been written on the theme too numerous to replicate here but here is a selection of thoughts. Galileo stated that “Mathematics is the language with which God wrote the universe” – not bad for starters! Oswald Veblen, a mathematician living in the last century said “Mathematics is one of the essential emanations of the human spirit, a thing to be valued in and for itself, like art or poetry.” To these men Maths was so much more than a few calculations undertaken in the lesson before break on a daily basis, to them Maths was a language to live by and a means of making sense of the world. It is often hard to recognise our “calculation-dominated” curriculum with either of the comments above but to be fair the Programmes of Study for the previous National Curriculum held philosophical statements for the teaching of each subject and calculation was not a major focus (indeed not even mentioned) in its rationale, It said: “Mathematics equips pupils with a uniquely powerful set of tools to understand and change the world. 2 These tools include logical reasoning, problem-solving skills, and the ability to think in abstract ways.” It went on to include the following quote from Professor Ruth Lawrence, University of Michigan “Maths is the study of patterns abstracted from the world around us – so anything we learn in maths has literally thousands of applications, in arts, sciences, finance, health and leisure! Recently I watched the film “Enigma”, a story about the codebreakers in the war based at Bletchley. Those seeking to decipher the codes were all mathematicians. At one point in the film one of the girls turns to Tom Jericho and asks him; “Why are you a mathematician? Do you like sums?” Tom replies “No, I like numbers, because with numbers, truth and beauty are the same thing. You know you're getting somewhere when the equations start looking beautiful” To those well versed in the subject, Mathematics is not about calculation. Calculators calculate and we carry these in pencil cases or access them on our mobile phones. Mathematicians are those who see the big picture, the patterns and relationships in numbers and how these relate to situations and problems in their world. Conrad Wolfham is a mathematician and the head of Wolfram Alpha that seeks to develop IT applications. His TED talk has had over 1 million hits and is entitled “Teaching Kids real Maths” It seeks to establish a clear rationale for the teaching of the subject. His premise is that any Maths problem is founded on four stages: 1. Posing the right questions (The key to finding any solution is to ask the right question) 2. Real World to Maths Computation (Taking a problem and turning it into a Maths based problem for analysis) 3. Computation (Crunching the numbers) 4. Maths formulation real world verification (Putting the solution back into the real world for verification) He maintains that schools are focusing their energies on the wrong elements of these four. “Here is the crazy thing” he says “in Maths education we are spending about 80% of the time teaching people to do step 3 by hand but this is the one step that computers can do better than any human… instead we ought to be getting students to focus on the conceptualising of problems and applying them and getting the teacher to run through with them how to do that.” I would contend that there is more than an element of truth in what he advocates. We live in the throes of a technological revolution that is transforming the world and transmuting every aspect of society. This new dawn is one based on logical thinking and reasoning more than any other skill and Maths is the native language of that digital world. Problem Solving set in this context In light of the above we need to be developing a fresh form of Maths that engages children on a totally different level. It is tragic to think that one girl said of her Maths lessons “In maths you just have to remember in other subjects you think about it” (quoted in Jo Boaler’s book “The elephant in the classroom”). But the truth is that much of our maths curriculum is “calculation focused” preventing children embracing the true Maths that those more conversant with the subject readily recognise. Quality problem solving resolves this tension. It has at its heart the observation of patterns. It develops persistence and risk taking alongside logical thinking processes that encourage children to tackle tasks systematically. They also develop the ability to recognise numerical relationships in their initial findings. 3 Jane Jones is the Chief HMI for Maths and in the “Ofsted Better Maths” series of conferences she stated that “The degree of emphasis on problem solving (and conceptual understanding) is a key discriminator between good and weaker provision”. This may well simply be due to the fact that it is these schools that have engaged most with the Maths teaching rationale and therefore are generally more cogent in their planning but whatever the reason good problem solving lies at the heart of good Maths teaching. It is interesting to note that none of this is a new message; the Cockcroft report published in 1982 described “problem solving as lying at the 'heart' of mathematics” The National Primary Strategy produced a document in 2004 in which they outlined the five types of problem solving they felt children should be engaged in: Finding all possibilities; Logic problems; Finding rules and describing patterns; Diagram problems and visual puzzles; Word problems. For reasons I have articulated above I would raise an objection to the inclusion of “word problems” and would place it back into the calculation section of the curriculum where I believe it truly belongs, but that aside the above offers a starting point for a framework. From here teachers need to source problems, either within the context of real world scenarios or from sources which deliver the type of Mathematician that we need to secure for the 21st Century. Without wishing to labour the obvious the quality of learning will be dictated by the quality of the problem the teacher sets for the children. But if we keep before us the attributes we wish to develop through these activities which are the key elements of; resilience, risk taking, creativity, posing questions, exploring through trial and error and latterly through a more systematic process it should be self-evident which will deliver these. As most teachers are aware the DfE Primary Strategy materials provide a good starting point and NRich is a quality resource, as is the newly created SPEAR Maths which seeks to present not just problems in themselves but also a framework to work within. Teaching Problems One of the points the Primary Strategy made to good effect in its document is that teaching needs to reflect the outcomes from the task. It states that, “Children need to be taught the strategies and to be shown how they can apply these systematically to problem solving. For many children the hit-and-miss approach they use when gathering information and their poor management of information limits their ability to work systematically.” (Problem Solving Primary Strategy 2004) Therefore teaching should focus on either creating and extending the open ended nature of the task or developing cogent strategies for children to solve such problems. Jane Jones showed the following problem to delegates at a recent conference. The problem is not complex in and of itself but she was encouraging teachers to focus on the strategies they used to solve the puzzle. The likelihood is that you spotted that the 3 cows 4 in the middle row must be multiples of 3 that total 15. From this point the puzzle starts to unlock. We should not assume that children will necessarily see this without a secure amount of scaffolding to support them. The lesson therefore needs to focus on the development of the systematic skills required rather than leaving children with the impression that the key feature is “finding out the value of the pig” All too often it is easy for teachers to lose sight of what the problem solving lesson is truly for and it reverts subliminally into a calculation style of lesson where the primary focus can become “finding the answer” But just as good calculation lessons should focus on the process and explore the most “effective and efficient” method (wording of the Numeracy Strategy), so the teaching of problems should not focus solely on the answer but on the mathematical skills and processes the children are gaining along the way. It is essential that children build on these throughout the Maths curriculum. Alan Schoenfeld makes an interesting observation related to this when he says that whilst the idea of problems has been always been a key element in the maths curriculum, problem solving has not. What he is seeking to clarify is that children need to develop a “toolkit” of “problem solving” strategies rather than accessing a series of answers and solutions to an eclectic group of problems unrelated in any form to each other. The Primary Strategy document sought to emphasise this with its advice regarding medium term planning. It suggested “Over a week, the children learn how to apply the strategies they have been taught in a particular lesson to similar problems in the following lessons.” There is more than an element of wisdom in this approach. There are of course a range of strategies that children should acquire under the umbrella of Maths Problem Solving. This might include: Trial and improvement – This is a valid starting point but we should ensure that children don’t stay there. Working systematically – finding all possibilities within a given problem Working logically – maintaining some inputs whilst changing selected variables Pattern Recognition – looking for rules within numbers, shape patterns etc. Conjecturing, generalising and improving – These are skills that are often generic to any problem solving solution but they undergird the thinking process for children Conclusion Having drawn from the old National Curriculum document in the early part of the document it appeals to my sense of symmetry to quote the new one at the end. The document outlines what it calls the “Purpose of Study” and states the following; Mathematics is a creative and highly inter-connected discipline that has been developed over centuries, providing the solution to some of history's most intriguing problems. It is essential to everyday life, critical to science, technology and engineering, and necessary for financial literacy and most forms of employment. A high-quality mathematics education therefore provides a foundation for understanding the world, the ability to reason mathematically, an appreciation of the beauty and power of mathematics and a sense of enjoyment and curiosity about the subject. Without wishing to labour the point the word “calculation” is not used but again the fullest and richest view of Maths is painted on the broadest of canvas. This is not to say that calculation is not important, as we all know it is a key building block in a child’s mathematical 5 development but it must not remain the sole raison d’etre for the primary curriculum. This would be to sell children, and indeed the subject of Maths itself, woefully short. 6