iNFRASTRUCTURE AND HYDROLOGY: improving the relationship

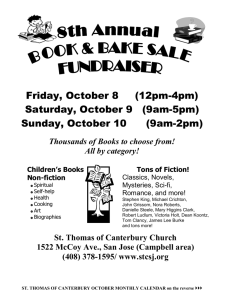

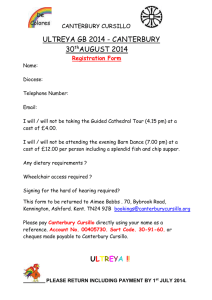

advertisement

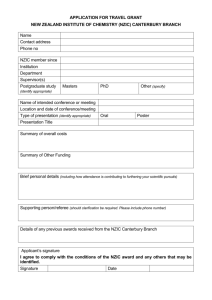

INFRASTRUCTURE AND HYDROLOGY: IMPROVING THE RELATIONSHIP AND LEARNING FROM THE RESULTS Jamieson, D., 1 1 ECan Aims Much hydrological science is undertaken to inform infrastructure practice. This paper reflects on how this process has evolved over time in New Zealand and specifically on what is occurring with water infrastructure in Canterbury. This paper focuses on how the overall impacts and opportunities from water infrastructure are becoming better informed by science rather than presenting detailed work on any particular type of water infrastructure. Method New Zealand (NZ) has been an active member of International Hydrological Programme (IHP) of the United Nations Scientific, Cultural and Science Organisation (UNESCO) since the 1960’s. The early days of the International Hydrological Decade (IHD: 1965-75) and IHP (1975-ongoing) coincided with an expansionary phase of NZ hydrology, when substantial investments in large infrastructure such as new highways with bridges and hydro-electric power schemes were made. More recently, owing to rapid economic and government changes, NZ’s role in IHP was limited. Nevertheless, IHP documentation was used to benchmark NZ hydrological activities with those of the rest of the world, and in particular introducing data telemetry. This paper discusses how water infrastructure practices in NZ have evolved over time. Current approaches in Canterbury are reviewed with a focus on how science (social and biophysical) is being applied to achieve multi-target outcomes and how these approaches align with the current phase of the IHP (IHPVIII). Results Considerable water infrastructure in Canterbury was developed before the inception of integrated thinking around multi-purpose infrastructure or multiple targets in water management. The current era of water infrastructure is notable for the withdrawal of Central Government from direct responsibility for operation and as far as publicly acceptable, ownership. While this process has not been completed in terms of hydropower, all substantial irrigation water supply infrastructure in Canterbury is owned and operated by the private sector. A feature of processes around any development has been the expectations of science. The role of science under the RMA was initially seen as being to lead thinking, resulting in approaches that have often been described as ‘science led’. Parties with contrary objectives typically commission science advisors who are engaged in a duel of opinions and experience. Frustration with this situation has led to a code of conduct for expert witness (Environment Court) and attempts to reconcile conflicting opinions through Expert Witness Conferencing sessions. The Canterbury Water Management Strategy (CWMS), developed under the auspices of the Canterbury Mayoral Forum representing all local authorities in Canterbury, is a process designed to refocus water management in Canterbury on a vision (To enable present and future generations to gain the greatest social, economic, recreational and cultural benefits from our water resources within an environmentally sustainable framework) based on multiple targets. Reports on progress against targets are produced at two year intervals. The role of science information has become one of informing processes with the best information available at the time of first engagement, with the utility of science based information and any information gaps being assessed in terms of CWMS targets. This assessment process applies to existing situations and to any changes, be they infrastructure based or otherwise. For New Zealand an important aspect of science is an understanding of how to achieve stream ecology outcomes given changed flows and nutrient status. Over time approaches to achieving outcomes have focussed on habitat availability e.g. Instream Flow Incremental Methodology (IFIM) in the 1970’s), minimum flow settings and more lately flow regimes. A recurring theme is that unexpected results have been occurring as science has struggled to understand the emergence of organisms such as Didymosphenia geminata (didymo) and Phormidium and the absence of biota of waterways with excellent habitat. The approach in Canterbury can be seen to be moving towards seeking an understanding of what is occurring to influence the state of waterways using current information and a consensus approach amongst all science personnel engaged, preferably on a collaborative science basis. While consensus amongst science personnel is ideal, but not always achievable, a primary focus is on making effective use of both existing information resources and to target additional science effort on the right questions. The key result emerging for New Zealand is that a locally initiated concept to improve water management in Canterbury (CWMS) has re-engaged with important international guidance via the UNESCO IHP. This is an important result for science and for water infrastructure practice in NZ, particularly as central government has made a substantial effort to improve infrastructure practices across all infrastructure types via the National Infrastructure Unit (NIU) of Treasury and the National Infrastructure Advisory Board (NIAB). As the CWMS progresses it is expected that implementation of IWRM and Ecohydrology at a regional scale (45,000km2), as opposed to a small experimental or pilot scale, will have important findings of international significance. For example engagement with other international processes (e.g. OECD water governance) indicates that there is considerable interest in the participation of Ngāi Tahu and incorporation of their cultural values in the CWMS. As this process continues it can be anticipated that NZ will provide international guidance on the incorporation of the knowledge and perspectives of indigenous people into the concept of Ecohydrology. References Canterbury Water Management Strategy Targets: Progress Report June 2015. Available at http://ecan.govt.nz/GET-INVOLVED/CANTERBURYWATER/TARGETS/Pages/targets-progress-report2015.aspx [Accessed 3 September 2015] The CWMS in our own words. June 2015. To be available at http://edit.ecan.govt.nz/getinvolved/canterburywater/telling-our-story/Pages/Default.aspx The Dublin statement on water and sustainable development (1991). Available at http://www.wmo.int/pages/prog/hwrp/documents/english/icwedece.html [Accessed 3 September 2015] Fox, A. (2001) The Power Game: The development of the Manapouri-Tiwai Point electro-industrial complex 1904-1969. Martin, J (1991) People, Politics and Power Stations: Electric Power Generation in New Zealand 1880–1998 (Bridget Williams Books) Mitchell D. T. History of the Ashburton-Hinds Drainage District. South Canterbury Catchment Board (1980) UNESCO IHP-VIII: Responses to Local, Regional and Global Challenges. Available at http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/water/ihp-viii-water-security/ [Accessed 3 September 2015]