Theories of collective behavior and social movements

advertisement

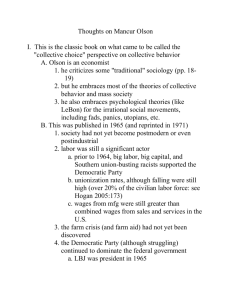

Sociology 525: Social Movements Spring 2010 Theories of Collective Behavior and Social Movements My outline of topics for this section (in the syllabus) is based on what I see as an historical progression of theories, beginning with LeBon in the 1890s, when conservatives attempted to understand the psychology of the mob, moving into the 1950s, when conservatives attempted to understand the social-structural conditions (particularly social disorganization and social change) that produce mass rebellion and social disorder. In the 1960s and 1970s, the dominant theory of collective behavior (called "collective behavior" theory and characterized by Turner and Killian [1957, 1972, 1987] and Neil Smelser [1963]) was clearly rooted in the conservative tradition of the psychology of the mob and the breakdown of social control. Generally, this theory was rooted in a Freudian theory of frustration-aggression and a Durkheimian theory of social control. - The Psychology of the Mob - LeBon: which you have read - McPhail: which is an excellent survey of psychological and social-psychological theories - Rudé: historical analysis of crowds - Zilborg: more sympathetic treatment of crowds - Mass Society and Social Disorganization Theories - Kornhauser: classic structural theory of mass society - Gurr: social psychological theory of strain - Davies: social psychology of rising expectations 2 This tradition was attacked by what appears to be a more liberal, "collective choice" theory, represented by Olson (and, more recently, by Brustein), who argue that collective action is rational. Individual's are profit-maximizing rational actors who engage in collective action (or refuse to engage in collective action) based on their calculation of the costs and benefits. - Collective Behavior versus Collective Choice - Olson: whom you read - Turner and Killian: classic collective behavior - Smelser: classic collective behavior - Oberschall: rational/collective chocie - Brustein: rational choice - Heckathorn: rational choice - Opp: rational choice - Marwell and Ames: critique of Olson/economists 3 In the 1970s, in the context of the debate between collective behavior and collective choice theories on the question of rationality, resource mobilization theory developed. As developed by Tilly in 1978, this perspective is rooted in Marxist theory, but it clearly shares some concerns with the Weberians—particularly the concern with organization. It differs from collective behavior and collective choice, primarily in its more historical, structural perspective on the relationship between social movements (or grassroots political struggles) and social change (changes in the institutional structure). While collective behavior has generally viewed social change as producing collective behavior (including social movements), collective choice has tended to view social movements as producing social change. Resource mobilization theory has attempted to specify the relationship. 4 - Resource Mobilization Theory - Tilly: pioneer in resource mobilization theory development (1978) and in historical analysis of contention (1986, 1995, 2004) - Gamson: major researcher in this area; did historical analysis early (1990 [1975]; has done media studies (1988, 1992, Gamson and Modigliani 1989) and small groups (Gamson, Fireman, and Rytina 1982) more recently. - Feagin and Hahn (1973): early challenge to collective behavior theory of ghetto riots; develop neo-colonial (Marxist/Leninist) theory - Piven and Cloward (1977): Lefty critique of politics of welfare capitalism and trade unionism; argue 5 against resource mobilization preoccupation with organization - Morris (1984): critiques Zald and McCarthy (1987) and other resource mobilization theories that focus on importance of Northern sympathizers for Civil Rights Movement - McNall (1988): challenges ideological and mass society theories of populism with Marxist class analysis Since resource mobilization theory has become the dominant perspective on social movements (and collective action), it has been challenged on two fronts. First, Skocpol (1979, 1980) and others (Skowronek 1982) argued that we need to "bring the state back in." We need to view social movements in the context of political capacities and crises that create 6 revolutionary situations and outcomes and largely determine the nature of political reform. This challenge inspired, to some extent, the development of political process models (Tarrow [1994] and McAdam [1982]), which (in my mind) provide a useful corrective to resource mobilization theory. - State Centered Theories - Skocpol: student of Barrington Moore who takes on Tilly and his students on Revolution - Skowronek: American historian who offers analysis of making of state in U.S. 19th Century - Bensel: political scientist who offers more nuanced analysis of class relations and commercial relations, sectionalism and, most recently, elections - Political Process Models 7 - Tarrow: seems most like Tilly, political scientist, perhaps less Marxist; studies Italy - McAdam: sociologist, Americanist; also a Tilly collaborator; also does more social psychological/identity politics, impact of activism, etc. The second challenge--new social movement theory is more difficult to evaluate. On the one hand, it is a return to psychological theories and the problem of ideology. On the other hand, it is part of a postmodern-poststructural critique of structural theories. Here it is less clear what the critique will yield in inspiring re-evaluation of the resource mobilization perspective. We can return to this question after we review the various theories. 8 - New Social Movement Theory - Epstein: not really a New Social Movements person, but part of the new “cultural turn” in sociology - Melucci: definitely New Social Movements (European) - Cohen (more of the same) - Kriesi (and Kreisi, et. al.; more of the same) - Offe (perhaps more critical/Marxist) - Scott (perhaps more readable) - Calhoun 1993: critiques New social movements - Plotke: critiques New social movements 9