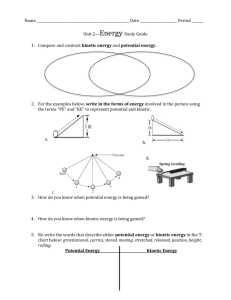

Manual - ScienceScene

advertisement